There were two things Brock McGillis knew from an early age: he loved being a hockey goalie, and he was gay. The Sudbury native started playing in net when he was seven years old and immediately felt he’d found his calling. He relished making a contribution to his team. “Every time a goalie makes a save, everyone cheers,” McGillis says.

When McGillis was six, he asked his parents, “What if I’m gay?” — the answer for which he hoped might provide some comfort. While his parents promised to accept him, he worried about his teammates’ reaction, and never mentioned his sexuality in hockey circles. He knew it wasn’t safe: even at 10 years old, he heard teammates using words like “fag” and “homo” on a daily basis in the locker room.

As he moved up the hockey ranks, joining the Great North Midget League in 1998 when he was 15, McGillis did everything he could to fit in. He put on a hyper-masculine guise, chewed tobacco, used a more rugged voice and walked around with a cocky swagger. He slept with as many women as he could, specifically choosing women his teammates found attractive. He even used homophobic language himself.

McGillis became what he calls a “bro,” a method of self-preservation. And the facade worked: he was a friend to his teammates and extremely popular at school. He felt like he was the object of female desire and male envy; once, he even had an autograph session at his high school. “I thought I owned the place,” he says. “I thought I owned the world.”

Internally, however, McGillis was suffering. Throughout his hockey career, which included professional stints in the United States and Europe in the early- to mid-2000s, he would get angry with himself when he felt attracted to other men. He drank heavily to suppress his thoughts and numb his pain, but the alcohol made him feel worse. He struggled with major depression, and attempted suicide on a number of occasions.

But at 22, he realized he couldn’t stop the thoughts — so he gave in. In 2006, while playing professionally in the Netherlands, McGillis logged onto a gay dating website. Once the season ended, he began going on dates with men.

McGillis’s experiences remain common more than a decade later. Cheryl MacDonald, a postdoctoral scholar at Saint Mary’s University in Halifax, released a study in 2016 in which she interviewed 30 elite male hockey players across Canada between the ages of 15 and 18 on topics that included gender, sexuality, masculinity and attitudes toward homosexuality. She found that, like McGillis, the players felt they had to possess certain hyper-masculine, heterosexual traits and qualities to be accepted. “In order to fit in, you had to be really competitive, mentally and physically tough and skilled on the ice,” she says. “It would help you if you were interested in partying with your teammates. It would help you if there was evidence of you being involved with women somehow.”

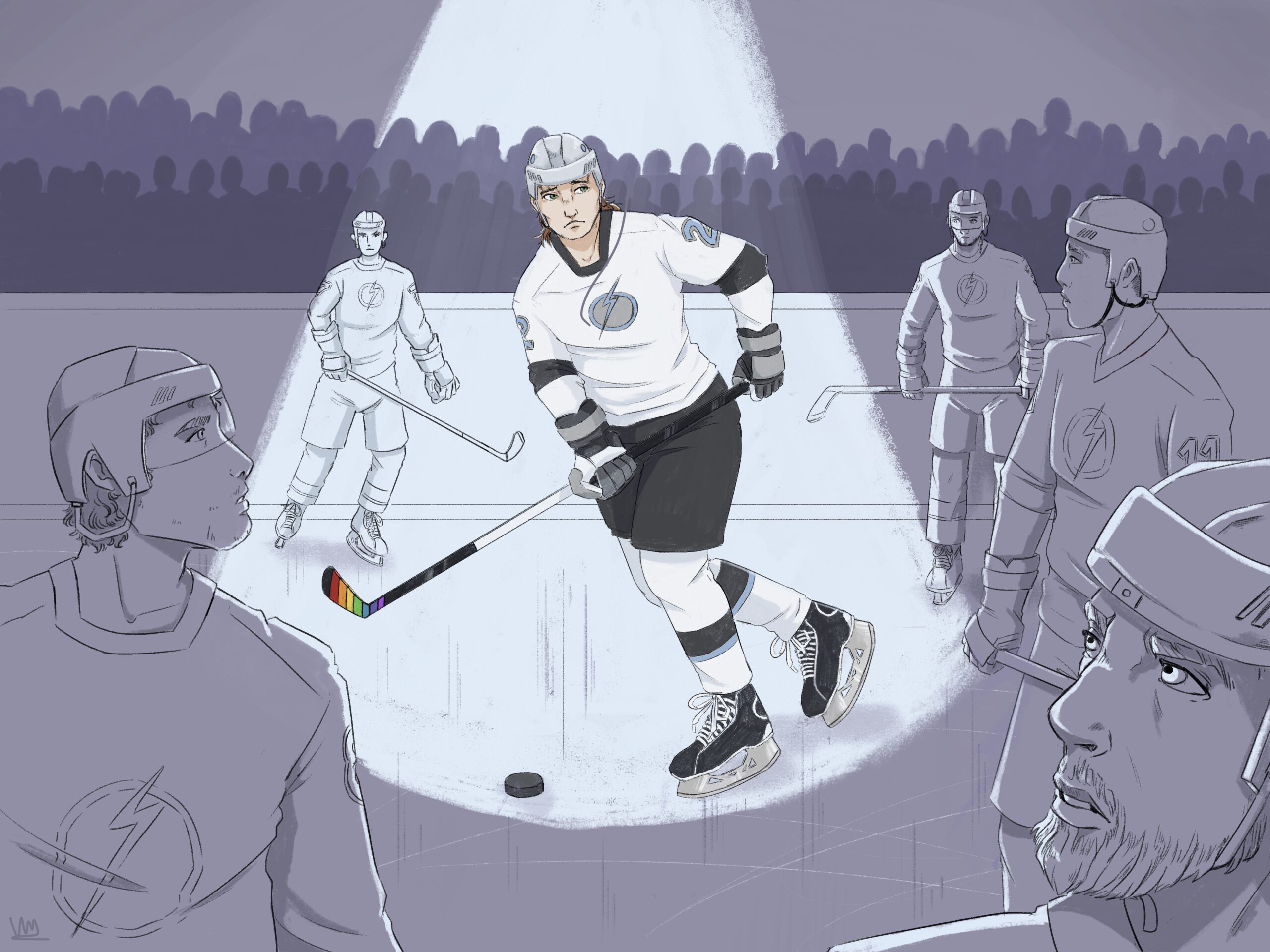

These findings come as little surprise. Other major-league sports have taken steps toward progress: former NBA player Jason Collins came out in 2013, and college football player Michael Sam came out in 2014 before the NFL draft. Women’s elite hockey is also known for its inclusion of LGBTQ2 players — some have even married players on competing teams. Still, no NHL player has ever come out as LGBTQ2, and for those playing in minor or junior leagues, there are few queer role models. But before men’s hockey can tackle its homophobia problem, the hyper-masculine environment that players feel pressure to conform to needs to change.

McGillis knows many gay players who failed to reach their potential for fear of discrimination.

One friend of his made the Junior B team at an Ontario university but had a boyfriend he didn’t want his teammates to find out about — so he stayed at a lower tier to hide his sexual orientation.

“Camilletti wonders: ‘I was more comfortable, could I have gone all the way?’”

Another friend, Daniel Camilletti, sometimes wonders if he could have made it to the NHL. As a 13-year-old in 2007, Camilletti was ecstatic to join the Toronto Marlboros, one of the top Triple-A teams in the Greater Toronto Hockey League (GTHL). But his excitement was short lived. “I had a higher pitched voice so everyone made fun of me for being gay,” he remembers. “People would say ‘fag’ in the locker room all the time.”

Camilletti had known he was gay since the sixth grade, but he didn’t reveal his sexual orientation to anyone. Instead, he put on a different persona around his teammates: he deepened his voice and acted tough. He also tried to act straight to better fit in. “I felt the need to have a girlfriend or hook up with girls because everyone else was doing it,” he says.

Camilletti was on track to be selected in the 2010 Ontario Hockey League (OHL) draft, but he decided to attend a boarding school in Pennsylvania instead. He knew that by forgoing the OHL, he was giving up his best shot to be scouted for the national league. “I couldn’t do an OHL lifestyle because it would feel like the locker room all the time,” he says, recalling the rampant homophobia that existed in the GTHL. “All they do is hockey, whereas at school, I felt like I had more of an escape and more of an outlet to do other things.”

After completing high school in Pennsylvania, Camilletti attended Tufts University, where he quit hockey for good. He joined the dance team, made gay friends and became passionate about film. Today, the 25-year-old is an assistant editor at a post-production company in Toronto.

While content with his current place in life, there are days where he ponders what could have been. “I was really good and worked really hard, but because I was treated so badly and it was such a toxic environment, I grew to hate it . . . I do sometimes think if I was more comfortable, could I have gone all the way?”

The kind of behaviours that Camilletti and McGillis exhibited in order to fit in can be traced to the relationship between the hyper-masculine persona found in locker rooms and what constitutes stereotypes of Canadian identity. Kristi Allain, a sociology professor at New Brunswick’s St Thomas University, studies the historical link between the Canadian national identity and ice hockey — a link she says came to exist in the mid- to late-19th century. Canadian settlers were looking for a uniquely Canadian game, free from American or British influence. The settlers “understood that a particularly violent and hockey-centric identity, one that differed from the gentlemanly masculinity of the British, would aid in the development of a distinctly Canadian sense of self,” Allain explains. As part of this identity, men needed to exude a hardened exterior and refrain from showing too much emotion.

In modern times, hockey commentator Don Cherry has played a major role in propagating this identity, Allain says. Cherry, who is known for his outlandish menswear and loud rants between periods of Hockey Night in Canada, supports a kind of masculinity that is linked to physical confrontation and keeping feelings in check. In a 2015 episode of Coach’s Corner, for instance, Cherry complained about the decrease in NHL fighting, saying that “nerds don’t want fighting.” And in February, Cherry criticized the Carolina Hurricanes, calling them “a bunch of jerks” for their elaborate post-game celebrations, which have included players pretending to go bowling or curling on the ice.

McGillis, who now speaks to elementary schools, high schools and junior hockey teams about the use of homophobic language in hockey, objected to Cherry’s criticism of the Hurricanes. “In this tone that I interpreted to be a whiny, sissy tone, he said, ‘Boys have feelings today. Young men have feelings today, and need to express themselves,’” McGillis says. “There’s a kid at home now who can’t tell his parents about his emotions because Don Cherry said [sarcastically], ‘Boys need to express their feelings today.’”

“Younger players often mimic major junior players, who they hear calling each other names like ‘fag,’ ‘bitch’ and ‘pussy’”

And it’s crucial for Canadian youth — especially those who identify as queer and trans — to be able to express themselves freely without fear of being mocked. Statistics indicate that bullying can have a long-lasting effect on suicide risk, and LGBTQ2 youth are much more likely to attempt suicide than their straight peers.

Despite this, McGillis says that homophobic language continues to permeate locker rooms today. Younger players often mimic major junior players, who they hear calling each other names like “fag,” “bitch” and “pussy.” When those players become coaches and team managers themselves, they continue to use the same outdated, homophobic words they did when they were kids. After speaking to one junior hockey team, for instance, the team’s coach told McGillis he’d always referred to the centre part of the ice in the defensive zone as “queer street.” It was a memorable way to keep players from passing the puck up that part of the ice; he just had remind them, “Don’t go up queer street.”

But McGillis says anti-gay language in hockey is more a product of hockey’s insular nature than contemptuous feelings toward LGBTQ2 communities: “I don’t believe that it’s necessarily intentional homophobia. I don’t believe that everyone in the room hates gay people.”

“In a situation where you don’t know who’s gay, there’s an assumption perhaps no one is”

Researcher Cheryl MacDonald agrees there might be some truth to that: many heterosexual players, according to her research, don’t understand the potential impact of homophobic language on the ice or in the locker room. Last year, she interviewed six straight former NHL players about their attitude toward homosexuality. The players always assumed that everyone in the locker room was straight, and as a result felt it was okay to use homophobic language to try and get under their opponents’ skin. “In a situation where you don’t know who’s gay, there’s an assumption perhaps no one is,” she says.

That attitude is still evident in the league today: In May 2017, Anaheim Ducks centre Ryan Getzlaf was caught by television cameras calling a referee a “cocksucker” during a playoff game. His supposed apology two days later made it clear he didn’t grasp the damaging repercussions of his words. “It was just kind of a comment,” Getzlaf said. “I understand that it’s my responsibility to not use vulgar language, period, whether it’s a swear word or whatever it is.”

It’s a Thursday morning in November, and McGillis is sitting in front of a few hundred high school students at Sudbury’s École Secondaire Hanmer.

When McGillis isn’t training youth hockey players, he has made it his mission to change attitudes on and off the ice. He knows that in order to create a shift, he can’t just denounce homophobic language. He also needs to crack holes in the hyper-masculine environment that players feel so much pressure to conform to.

Chatting with the students, McGillis lists off his hockey credentials — past member of the Windsor Spitfires and Soo Greyhounds, stints in the United Hockey League and Dutch Professional League. Once that grabs their attention, he tells the students he’s the first openly gay former professional hockey player in the world.

“Do you know anyone who identifies as LGBTQ2?” he asks, and most of the students put up their hands. Then he stands up to shake hands and introduce himself to the rest.

The students aren’t as receptive when he asks if they’ve used homophobic language. “No one will get in trouble,” he prods. “You can be honest.” Then, a prompt: he raises his hand first. The students follow, one by one.

McGillis shares his story, explaining the impact that homophobic language had on him throughout his hockey career — so much so that he nearly ended his life. “I try to make them realize that if I, someone who wasn’t bullied, tried to kill myself because of the language I heard, what about the people who are being bullied?”

McGillis isn’t the only one battling for change. In 2012, the You Can Play project was launched to help fight homophobia in sports, and became an official partner of the NHL the following year. And since February 2017, each NHL squad has designated one player to be the team’s You Can Play ambassador. Teams host You Can Play awareness nights, aiming to promote inclusivity.

But McGillis feels that in order for real change to occur, there has to be more work at a grassroots level. Language needs to change, and young players need to be more willing to be vulnerable and open with one another. It’s why, when he speaks to junior hockey teams, McGillis goes around the dressing room, asking each player to say something about themselves they wouldn’t usually share with their teammates. One player said he liked writing poetry. Another one said he loved watching animal documentaries. “When everyone feels that it’s okay to share, they share,” McGillis says — and that alone can help change attitudes.

“We have to educate them that they don’t have to fit and conform to this mold of what a hockey guy is.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra