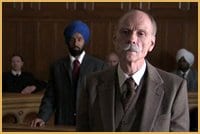

Credit: Out On Screen

Since so much of queer history has gone unrecorded, an area of paramount importance has been unearthing stories that have been erased, ignored or forgotten.

A trio of celebrated Canadian filmmakers is now drawing attention to a little-known case of government entrapment of Sikh labourers near the turn of the last century, in a short video titled simply Rex vs Singh that will have its world premiere at this year’s queer film festival.

The 20-minute work, which was commissioned by festival organizers Out on Screen as the latest installment in their Queer History Project, is inspired by a specific 1915 court case wherein two Sikh mill workers, Dalip and Naina Singh, were entrapped by undercover police and charged with sodomy.

One of the unusual things about this case is that it was not unusual; Sikhs were being charged on a fairly regular basis with such acts (in fact, there were numerous cases titled “Rex vs Singh”).

These trials were brought to public attention through the work of Vancouver-based university instructor and historian Brent Ingram, who wrote a piece in which he delved into the court transcripts of these cases. According to Ingram, Sikhs were singled out for entrapment because, as British subjects, they arrived with a full set of rights and privileges, which meant they were immediately resented by the white majority —and, by extension, the police. “Certain white people in Vancouver were not happy about this,” says Ingram. “The early ‘city fathers’ of Vancouver were all white and often quite racist. They didn’t want Indo-Canadians becoming a significant demographic group in Vancouver, and by sexually harassing them they hoped to make these men feel unwelcome.”

Ingram says these court dossiers document urban relationships that prefigured modern resistance to attacks on sexual minorities.

“These trials functioned to equate intimacy between adult males (various forms of contact, affection, and sex) with the new Canadian statutes against ‘gross indecency.’

“Before these early 20th century laws for gross indecency,” he notes, “the laws were really against ‘buggery’ only (anal penetration) whereas these trials against Sikh males for ‘gross indecency’ were for a much wider range of affectionate behaviour and sexual activity than had been discussed in trials in British Columbia.”

When Out on Screen approached John Greyson (whose Lilies took the Genie for best picture in 1997), the Toronto-based filmmaker suggested using Ingram’s work on these cases as a launch point for an experimental project. Of the numerous cases they looked at together, this particular case seemed the most captivating.

“This was a very complex case,” Greyson says. “There was also some very racy testimony, full of very literal descriptions of sexual acts.”

The testimony and accusations include discussions of pants being dropped, erections and repeated use of the word “fuck”- in other words, not what we tend to think of as Victorian-era stuff.

But with Greyson spearheading the project, the last thing anyone would expect is business as usual.

“I thought it would be great if several of us got together and each created our own take on the trial,” he says.

Greyson invited two other Toronto-based filmmakers to collaborate: Richard Fung (Sea in the Blood, Chinese Characters) and Ali Kazimi (Continuous Journey, Narmada:

A Valley Rises). The first segment is what Greyson describes as a classical courtroom drama.

“We used Witness for the Prosecution as a model,” he says. “We filmed it in the Old City Hall in Toronto, which is still used as a courtroom, so that added another dimension to the segment. We all have a great love of classic realist cinema, so we wanted to make it work on those terms.”

But Greyson, Fung and Kazimi also liked the idea of stepping back from this typical and generic cinematic treatment of history and then posing a series of questions. “We felt this would be not only about the enigma of history,” explains Kazimi, “but about the enigma of retelling history.”

Those familiar with the Greyson oeuvre will instantly recognize this approach —of recounting historical events while simultaneously deconstructing them.

After the classical narrative segment is complete, Greyson directs a musical segment, Fung offers an experimental take on the events, and Kazimi does a documentary treatment (albeit a very unusual one).

For the team behind Rex vs Singh, the very fact that many of the questions surrounding the case remain unanswered made it all the more intriguing as a story. Unlike

a Hollywood studio courtroom drama, for example, Rex vs Singh will offer no easy answers, but rather raise a series of questions.

“Were the men having sex?” asks Greyson. “Or were they just entrapped? We don’t even know what the verdict was in this case —that part of the story has never been uncovered. There is so much about it that is unknowable, that is mysterious. This is a video about fragments of a story —the more we try to answer them, the more they fall apart.”

For example, Ingram points out, it’s unclear if they were actually gay men, or just men who’d been targeted by police due to racism. “We don’t know enough about these individuals to know if some or all of them had exclusive homosexual or even bisexual identities,” he says.

And the question of how these men identified is all the more absorbing, given that the very concept of a gay male identity didn’t exist at the time.

“The legal notion of the ‘Homo Sexual’ —that’s how it was written in Canadian court records —as somebody who identified with their homosexuality wasn’t really articulated in Canada until the late ’20s and ’30s. So these trials were a few years before that,” Ingram explains.

Kazimi adds that these cases represent a fascinating intersection between homophobia, racism and state power.

“Richard Fung pointed out that before these cases were brought against Sikhs, the Chinese migrant worker community had been hit with similar charges in the mid-1800s. The police were targeting these communities.”

Something else struck Kazimi when he read through the transcripts. The two Sikh defendants, who spoke in Punjabi and had a translator, were not helpless victims.

“Too often, when we engage in historical representations of situations like this, we re-victimize the people. I think it’s important to recognize their dignity,” Kazimi emphasizes, noting that their words of resistance are actually quite profound.

“When asked, they outed the cops who entrapped them. These two Sikhs actually refused to be cowed by the trial. For us, that was something that was very important to convey,” he says.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra