After more than three decades of activism the Coalition for Lesbian and Gay Rights in Ontario (CLGRO) is preparing to close down.

The organization’s demise will leave a huge void when it comes to sex-positive activism and a willingness to take on controversial issues, say CLGRO members and queer activists.

A meeting of CLGRO’s steering committee on Jan 10 decided to recommend to the membership that the organization close down. A final vote will be held at CLGRO’s annual meeting in May.

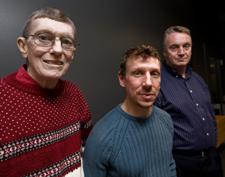

Tom Warner — who has been a member of CLGRO since its founding in 1975 — says the organization’s membership is aging and dwindling.

“We have tried to draw in more members, particularly younger members, and we haven’t had much success,” he says. “Our ability to organize around an issue is a real question. A demo, an action, even a press conference would challenge our resources at this point.”

But Warner says he’s proud of what CLGRO has accomplished in its time as an activist force in the province.

“We’ve been around for a long time and we’ve achieved a lot,” he says. “I don’t think there’s an organization that’s been around as long as we have that’s accomplished as much.”

Certainly a list of the issues CLGRO has tackled includes most of the major fights for queer rights in Ontario over the past 30 years. CLGRO was the leader in the successful fights to change Ontario’s Human Rights Code and to get the Toronto District School Board (TDSB) to adopt a non-discrimination policy. The group also helped lead the fight against bathhouse raids and in defence of The Body Politic — Xtra’s predecessor — when it came under attack from the government. CLGRO was a pioneer in calling for reforms to make the health system in Canada more queer-friendly. Work by CLGRO led to the formation of the Rainbow Health Network and the Triangle Program — the TDSB’s program for queer students.

CLGRO also was a groundbreaker in the fight for recognition of same-sex relationships, a struggle that eventually culminated in same-sex marriage. CLGRO was also one of the very few groups that fought for other types of recognition and against the increasing mainstreaming of queer relationships. In the last few years CLGRO was also one of the few queer groups willing to fight aggressively against oppressive sex laws and raising the age of consent.

“A lot of people felt 14 was too young and 16 was okay,” says Warner. “You could say that marriage has killed sex. My experience is that the community doesn’t thank you for talking about sex and in fact tries to marginalize you. I find that that very concerning.”

So does Ken Popert, the executive director of Pink Triangle Press — which publishes Xtra — and one of the founders of The Body Politic.

“Activism is basically nonexistent,” says Popert. “[CLGRO’s demise] leaves the field of speaking on behalf of gay people to conservative organizations like Egale, who have a civil-servant mentality when it’s not a social worker one.

“Egale has made a career so far of fleeing from sex. The only thing that’s ever embarrassed Egale into taking the occasional stand on sex-related issues was CLGRO.”

Andrew Brett, the founder of the Age of Consent Committee, agrees CLGRO’s absence will be felt on sex issues. He says CLGRO was tremendously supportive of young activists in the unsuccessful fight against raising the age of consent.

“CLGRO is one of the very few queer liberationist organizations out there,” he says. “When you’ve got a bunch of kids trying to take on the government, it can be overwhelming. When you have an organization with that longevity and activists who have been around for a while, it’s tremendously helpful. What strategies to try, even how to draft a statement to the justice committee, these are all things they had advice on.”

Nick Mulé, a 20-year member of CLGRO, says the focus on same-sex marriage ultimately led to a marginalization of that sort of sex activism and of CLGRO itself.

“What I wanted was a debate on ‘Did we want to enter this institution?,” he says. “It wasn’t a voice that was picked up a whole lot. I do find myself sitting and wondering how marriage has benefitted us or our options, our choices, our diversity. I still don’t support it.”

And Warner takes satisfaction in knowing that time and the few Canadian queers who have married may prove CLGRO right.

“I’m actually, gratified is not the word, but not surprised that the number is so small,” he says.

And despite CLGRO’s marginalization Mulé does point proudly to the existence of organizations like the Rainbow Health Network, which grew out of one of the very few instances of CLGRO receiving government funding.

In 1992 the organization received money from Health Canada for Project Affirmation to study the health and social service needs of sexual minorities in Ontario. Five years later Systems Failure, the finished report, was released only to sit on a government shelf. To try to implement some of the policies CLGRO formed the Rainbow Health Network in 2001.

“The Rainbow Health Network is still officially a reference group of CLGRO,” says Mulé.

Popert says CLGRO has also played a lasting role in the fight against police abuses, and particularly in curbing Julian Fantino and his Project Guardian witch-hunt for child porn among gay men while he was police chief of London.

“The organization has continued to play a very good role in fighting arbitrary police power and defending sexual freedom of gays and lesbians in particular,” he says. “I think it was CLGRO who managed to plant an indelible stain on Fantino and rightly so. I think that’s an important contribution, their role in Project Guardian.”

But for all its accomplishments the longtime members of CLGRO do have regrets, especially around the problems that continue to be faced by queer students and youth in schools and rural Ontario.

“It’s kind of unfortunate that we couldn’t mobilize more around the education issue,” says Richard Hudler, who joined CLGRO in 1979. “It’s kind of unfortunate that we couldn’t maintain the provincial focus. People in the rural areas are suffering as much as they were in 1975.”

Part of the reason for that, says Warner, is that the community didn’t fully support groups like CLGRO.

“If I want to be really cynical I would say the community doesn’t really care,” he says. “The community has always expected CLGRO to be there for them but they weren’t ready to be there when we needed them.”

But CLGRO may not be ready to completely die just yet. Mulé has put forward a proposal that would see a greatly reduced online version called Queer Ontario.

“Queer Ontario for the most part would have a virtual existence via a website that would showcase the history of CLGRO and a series of positions on contemporary issues affecting queer communities in Ontario,” he writes. “A regularly updated blog could also be created, a listserv for ongoing discussions as well as the possible use of podcasts.”

Warner says that if queer youth ever come under attack from governments or police or decide they need to focus on sexual liberation issues again, members of CLGRO might still be available.

“There might still be some of us around with our walkers and hearing aids to help them,” he says. “I have to be optimistic. We didn’t know all of this. We learned. They’ll learn too.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra