There’s a particular kind of void left by losing someone dear to us, especially if they’re young, so young that it defies what we thought are the laws of nature, especially if they’re family, especially if their deaths are associated with a disease that has claimed the lives of more than 30 million people worldwide since the beginning of the epidemic.

Behind that statistic are people who refuse to forget, friends who continue to tell tales of revolutions, family members who recall building sculptures on the kitchen table and lovers who remember cold autumn mornings listening to music and sipping hot chocolate.

In honour of World AIDS Day, Xtra spoke to three people whose lives were directly affected by the HIV/AIDS epidemic. They are friends, family and lovers of the departed—people who continue to remember and fight to never forget.

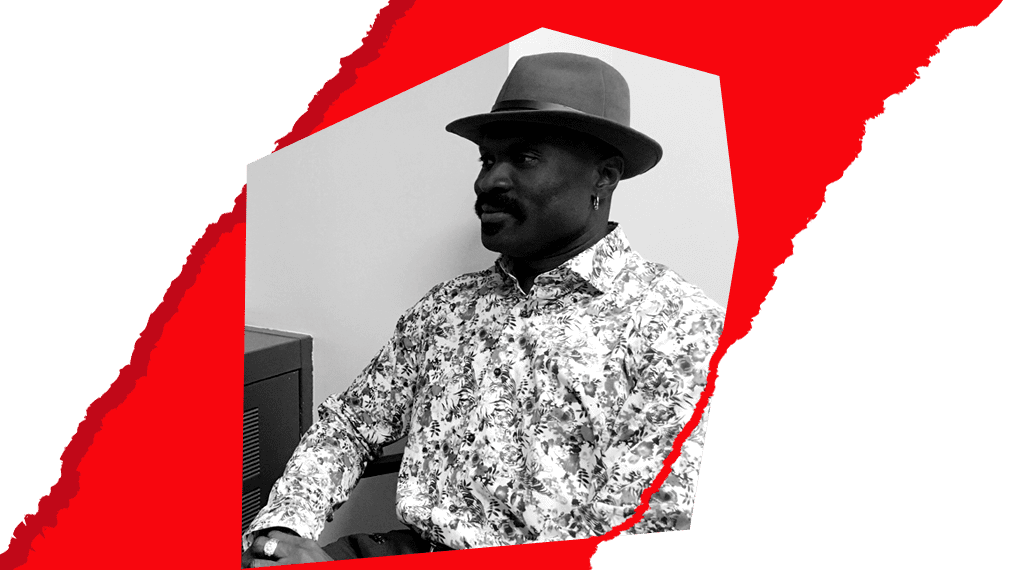

The Friend: Remembering Euloge aka Akissi Vis-à-vis

Carlos Idibouo remembers Euloge on World AIDS Day. Credit: Arvin Joaquin/Xtra; Francesca Roh/Xtra

A woman with big pretty eyes in a traditional dress walks in one of the markets in Abidjan, Ivory Coast’s economic capital. All eyes are on her as she struts along the busy street, some women whisper to their friends, “Are you seeing what I’m seeing?”

From the market’s entrance, she points at the onlookers. “You! You! I can see you!” she says. “If you tell me what you’re telling your friend, I’ll come over and tell her who I am.” She continues. “If you’re trying to figure out things about me, I’m here. So you don’t have to struggle with that.”

The whispering women shuffle away, saying, “No, no, it’s okay.”

As a trans woman, Euloge (we’re only using her first name for privacy) was used to people staring at her because she challenged what was perceived to be acceptable. But according to friends, she always had a way to win over other people’s hearts.

“She was a straightforward person, but she was lovely,” her friend Carlos Idibouo says, recalling that day in the market back in their home country more than a decade ago. “She always told people that, ‘you know, if I’m talking to you like that, believe me, it’s because I love you. If I didn’t love you, I will just ignore you.’”

Idibouo worked with Euloge, who died in 2006, organizing one of Ivory Coast’s first LGBTQ organizations in 2000. At one point, they even lived together in a home they shared with five other people.

“The following Sunday she goes back and the women were laughing and joking,” Idibouo says. “She became friends with all of [the women in the market].”

Euloge, fondly referred as Akissi Vis-à-vis by her friends—Akissi, a name from one of Ivory Coast’s local languages, is typically given to girls born on Mondays and Vis-à-vis a French phrase meaning in relation to, usually facing something or someone—had a huge personality and charm that would make people look at her the moment she entered the room.

“Akissi Vis-à-vis basically means someone who is not afraid to tell the truth,” Idibouo says. “Nothing scares her, ‘I will tell you the truth when I see you,’ that’s how she was.”

Euloge was also one of the first trans people to serve the LGBTQ community, as well as a health clinic that addresses the needs of the trans community in Abidjan.

Idibouo says when he and Euloge created the organization, Arc en ciel Plus [Rainbow Plus], its first partnership was with a clinic serving women sex workers.

He recalls meeting with the physician who worked at the clinic they partnered with and told him that there are sex workers in the LGBTQ community who don’t have anywhere to go to get tested because of fear for their safety.

“I told him, ‘when they are infected or have any kind of STI, I don’t even know how to treat it. That’s why most of them died,’” he says.

Having Euloge in the clinic helped because trans people who wouldn’t go to clinics if they couldn’t identify someone from their community ended up going and getting tested.

“HIV was destroying relationships no matter what kind of relationship it was—family, friend, lovers.”

“You know, I was working at the clinic as a manager and having Akissi Vis-à-vis around really motivated people to come to the clinic to get treated,” he says.

Euloge’s HIV/AIDS-related death in 2006 greatly affected not just Idibouo but the entire LGBTQ community. In fact, after Euloge died, he couldn’t find anyone else to run the organization with. In August, that same year, Idibouo moved to Canada.

He says losing someone like Euloge, someone who was helpful, fearless and charming affected how he continues to live his life and also his advocacy as an HIV/AIDS activist.

“HIV was destroying relationships no matter what kind of relationship it was—family, friend, lovers. I don’t know what other pandemic destroys human beings’ lives the way HIV did and still doing because stigma is too strong.”

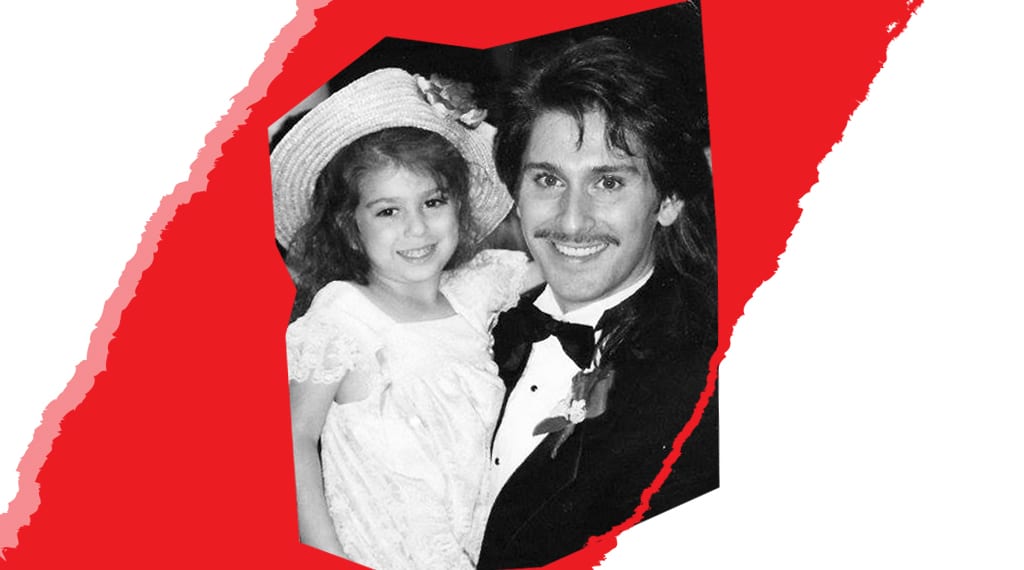

The Family: Remembering Allan Koppelberger

Ash Abraham with her uncle, Allan Koppelberger Credit: Courtesy Ash Abraham; Francesca Roh/Xtra

While on a hospital bed—which would later become his deathbed—Allan Koppelberger catches the look of pain in the eyes of his niece, Ash Abraham. He is hooked up to an IV line, his condition deteriorating, but his sense of humour remains the same.

“I know, I know, it’s ridiculous,” Koppelberger says, referring to his state.

Koppelberger loved to make other people laugh. He was a great impersonator, a joke teller and a brilliant pianist.

He lived in Nashville as a musician and a songwriter. To Abraham, he’s “unc”—a permanent figure growing up.

Koppelberger stayed with Abraham’s family on and off and Abraham doesn’t have a lot of memories where unc’s not around.

“There’s not a birthday party that I don’t remember having him not there,” she says.

Growing up, Abraham and Koppelberger would create pieces of art together on a big table at Abraham’s mom’s apartment. The two would make crafts and sculptures.

“I feel like I lost a friend—a friend you can’t replace.”

“I have a lot of memories of sitting around the table. I’m sculpting with him or sometimes we just have a bunch of paper and we doodle and draw comics together. Sometimes we’d watercolour,” she says.

But Abraham also recalls unc being sick and needing to spend time in the hospital. Then in 2001, when Abraham was 14, Koppelberger’s condition deteriorated.

“I was actually watching a movie when he passed away. My dad came early in the theatre to just sit with me,” she says.

She was aware that her unc’s condition was worsening, so sitting beside her dad that day, she recalls, “I’ve kind of figured, okay, this must be it.”

And it was.

Koppelberger—unc—passed away at 38.

“You feel like a big part of your soul is not on earth anymore, you feel like punched even as a kid,” she says. “My uncle and I had this weird relationship where he’s a friend and a brother because he’s young, so I feel like I lost a friend—a friend you can’t replace.”

“It only made me love him more and have more understanding for the kind of pain that he was in at the time.”

In 2007, while Abraham was away in Nashville and then Knoxville, Tennesse for school, her mom decided to move to Boston. Since her mom was moving to a small place, she gave most of her stuff to Abraham’s dad and Abraham inherited the rest.

Abraham was left a black bag with an instruction: “Make sure to take care of this bag. Don’t put it in the basement, keep it in your room.”

She didn’t explore the contents for two years. But then, in 2009, she opened it. Alongside photographs and legal documents, she discovered Koppelberger’s death certificate. She read the document and saw the cause of his death: AIDS related.

When Koppelberger passed away in 2001, Abraham’s family had told her that her unc died of cancer. Eight years later, after learning the real cause of unc’s death, she confronted her mom about the way they talk about and remember unc.

“My mom said, ‘I didn’t want you to see him any differently,’ which broke my heart because it only made me love him more and have more understanding for the kind of pain that he was in at the time,” Abraham recalls.

Abraham remembers Koppelberger on World AIDS day but she says what’s funny is the public remembers her unc, and others who died because of the AIDS epidemic, on a day that she says she’s not sure if her unc would have actually wanted to be associated with—a day that’s still so heavy, a day full of mourning.

“He was the opposite of that. He was full of love and happiness and joy and so creative and he was also very faithful,” she says.

“I think he would want to be remembered as somebody who tried his damnedest—period.”

The Lover: Remembering Gilles Godbout

Jeff Bale remember ex-lover, Gilles Godbout. Credit: Riley Sparks/Xtra; Francesca Roh/Xtra

A pear-shaped bottle with a red cap has seen countless mantelpieces, been on various shelves and will always conjure memory of fall weekends, good coffee and the sound of someone’s laugh.

“The cologne by itself smelled amazing. On him, it made my knees shake,” Jeff Bale says as he remembers his former partner, Gilles Godbout and Godbout’s signature scent.

“I saved that bottle, and it sat in any mantelpiece, on any shelf I’ve used in every place I’ve lived in, the last 21 years.”

“The cologne by itself smelled amazing. On him, it made my knees shake.”

In one of the apartments in Montreal, songs by Cuban singer Ray Barretto fill the air. It’s a weekend morning, and the fall weather produces a convoluted mix of sun, rain and cloud.

The apartment is suffused by the smell of brewed coffee and on the settee sit two men. One of the men wears an undershirt and underwear looking both serious and goofy at the same time. His raspy voice emerges when he speaks, the kind of voice that smokers have.

The other man looks and listens intently, enamoured by his partner, a good dancer, a talented artist with incredible style, someone who introduced him to theatre and other scenes the city has to offer.

That morning, in between coffee and music, a memory was made—a memory so hard to forget.

Bale met Godbout in the summer of 1995, just after the second Quebec independence referendum. As Americans, Bale and his parents regularly traveled to Montreal to celebrate Christmas and New Year’s Eve. They stayed at the Auberge Les Passants du Sans Soucy so frequently that Bale developed a friendship with the then-owners, who were a gay couple.

They invited Bale to work for them during the summer—and eventually introduced him to Godbout. Bale and Godbout hit it of and they dated that year. When Bale had to go back to the US for graduate school, the pair continued to communicate via phone calls, letters and $50 Amtrak trips from DC to Montreal.

“I definitely went to Montreal more often than he came to DC probably because it has impacts on his health,” Bale says as he recalls the on-and-off relationship with Godbout. Godbout was several years older and had been living with HIV for a while at the time.

The pair continued to visit each other in the span of two years.

“Language limited how much I would ever be integrated into his life [in Montreal],” Bale says.

Regardless, the two remained in each other’s lives until July 9, 1997 when Godbout died of AIDS-related illnesses.

“I’ve only been to one funeral in my life and it was for my paternal grandfather which was a closed casket,” Bale says.

Godbout’s service was different. Bale recalls there was a table in front, instead of a casket, on top of it was an ornate box and next to it was the spot where people who want to commemorate Godbout stand; but Bale found the ceremony difficult to follow along with as it was in French.

“I just didn’t know what they were saying and I didn’t know what to say. It took me half the service to realize that the ornate box was his ashes so people kept referring and pointing and gesturing towards this box,” Bale says. “Then I realized, ‘that was Gilles [in the box], it’s his ashes.’”

Bale says that moment was very profound because it emphasized that he never really had the chance to get to know Godbout as a whole and vice versa—because of language and because of distance.

“She said to me, ‘we’re really glad you’re here, he loved you very much.’”

During Godbout’s funeral, one of his relatives who Bale had never met approached him. The woman spoke to Bale in English.

“She said to me, ‘we’re really glad you’re here, he loved you very much,’” Bale recalls.

“I remember how much that meant to me because it was a totally unnecessary thing but very thoughtful thing for her to say to go out of her way to tell me that his family was glad I was there.”

When Bale heard of Godbout’s death, he experienced immense loss over someone he loved, but he didn’t really have a community of people who knew Godbout well enough that he could grieve his death.

“My friends in DC knew I had some guy in Montreal I used to go see and now he’s dead,” Bale recalls. “But I couldn’t really grieve with people there cause nobody really knew him . . . I was part of his life in a small way and he was part of my life in a small way in DC.”

Bale also felt like he didn’t have the right to grieve when it was only for one person.

“I am not part of the cohort of gay men who experienced huge amounts of loss,” Bale says. “I remember thinking that I didn’t really have the right to say a word to commemorate publicly or to share this thing publicly because it wasn’t that amount of grief that compared to other kinds of loss and grief that other gay men experienced. I couldn’t even really seek preservation of people because it was just the one versus [hundreds of] people.”

“I told everybody how funny he was, how beautiful he was and how happy he made me. How much I loved him, missed him.”

But this changed in 2017, 20 years after Godbout’s death. Bale decided to join the Friends for Life Bike Rally, a six-day, 600-kilometre bike ride from Toronto to Montreal done to raise funds to provide services and support to individuals living with HIV/AIDS in Toronto.

“A friend of mine runs a company that makes bike decals. He made a decal set for me that has Gilles’ name and the day in which he died, and I put that in my bike,” Bale says.

He says he knew he was doing the ride in honour of Godbout’s memory but it took him a while to finally admit it in front of others because he was so used to grieving Godbout’s death in private as he thought that he didn’t have the right to mourn one person’s death when other gay men loss many.

But this changed on an open mic night during the rally’s candlelight vigil where everyone was encouraged to speak about why they were riding and who they were commemorating.

“It actually was so freeing to be able to call his name out in front of people [again] and talk about him. I talked, maybe, for two minutes. Nothing more than a few words,” Bale recalls.

“I told everybody how funny he was, how beautiful he was and how happy he made me. How much I loved him, missed him.”

Bale recalls one of Godbout’s most memorable visits to DC sometime in the mid- or late ’90s when Godbout left an empty bottle of cologne.

Bale says the scent of the cologne was long gone but the scent lasted around 10 years.

“Every time I opened it up and let more scent out—the sensation of that scent is so endearing,” Bale says. “It gives me a chance to reflect on him and memories of him.”

This story is part of our coverage on World AIDS Day.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra