This is a story that Peter MacKay doesn’t want you to read. In the fall, Canada’s defence minister signalled that there would be no compensation for Canadian veterans dishonourably discharged for being gay.

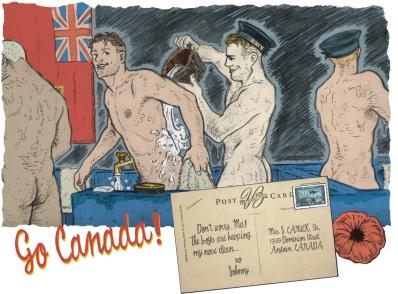

While there was a well-documented purge of gay servicemen during the ’60s, ’70s and ’80s, the realities of gay life in the military a couple of decades earlier were quite different. During the Second World War, some gays were turfed, while others were tolerated. Often, getting kicked out of the military for being gay had to do with circumstance — when Canada’s troop levels ran low, gays were far less likely to be discharged.

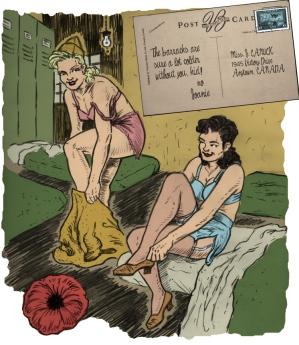

But for a generation of young men and women, the Second World War was both their coming of age experience and their opportunity to come out. The war changed the world of gay life indelibly.

For example, American queers can thank Second World War veterans for laying the foundations of gaybourhoods across America.

So goes the tale told by John D’Emilio in Sexual Politics, Sexual Communities — what has become one of the most important queer history texts of the last two decades.

The book traces the origins of gay villages in the United States to the port cities where soldiers and sailors spent much of the war. D’Emilio argues that gays returned to these cities in droves during peacetime because, as queer people, they no longer felt comfortable in their hometowns.

“For many gay Americans, World War II created something of a nationwide coming out experience,” D’Emilio wrote.

Canadian gays might not have contributed as dramatically to the growth of their cities when they returned home after serving overseas, but several years of war nevertheless helped thousands of young men and women explore their sexuality.

Montreal writer Paul Jackson has found that the war not only showed soldiers a world they had never seen before, it also revealed a way of life that was equally foreign.

“For many queer servicemen, the transfer overseas represented a break with heterocentric Canadian social structures,” he wrote in One of the Boys, a book that chronicles the wartime experiences of Canadian gay men. “Many found new opportunities for sexual self-discovery.”

In World War II, Canadian women served an increasingly crucial role, often in sex-segregated environments, as medics, mechanics and support staff. Upwards of 50,000 Canadian women were shipped to theatres of conflict (although they did not fight in battle) during the war. Lesbian conduct while overseas was often condoned or ignored by the allies, according to D’Emilio.

But Jackson doesn’t embrace D’Emilio’s claim that the Second World War gave birth to gay neighbourhoods — in Canada, at least. He says that similar sex-segregation happened during the First World War, and there is no evidence that gaybourhoods popped up afterwards.

Jackson adds that sex-segregated environments also existed long before Canada’s military ballooned at the outbreak of the war — at logging and fishing camps, for example.

Working-class men were often separated from women in Canada, he says, and but those environments didn’t spawn the gay enclaves that now exist in Canada.

Nonetheless, during World War II, military bases (which were already homoerotically charged) became brazen cruising zones. So it’s not surprising that one of the most prominent wartime hotspots for gays developed in one of central Canada’s traditional military strongholds — Kingston, Ontario.

Marney McDiarmid, who wrote her master’s thesis about Kingston’s queer history, says the war transformed the city’s relatively quiet gay community. She wrote that, during the conflict, “the sheer presence of so many young men, far from home, transformed city streets into sites of sexual possibility.”

For years after the war, the Kingston garrison remained quite large. Six thousand men were stationed in town as late as the 1960s. McDiarmid detailed the experience of one man, identified only as Earl, whom she interviewed about that period of time.

“One of the great hobbies was to get in your car and drive the La Salle Causeway,” he said, referring to the road that bridges the Cataraqui River between downtown and the army base.

“[Soldiers] were short of money — naturally, in the military, they weren’t paid too well — and they were always walking up the hill,” he said. “So you’d stop and offer a lift, and they’d get back a lot later than they should have.”

But McDiarmid said that the military presence in Kingston eventually shrank and had little impact on the growth of the city’s queer community — unlike San Francisco and New York City.

D’Emilio wrote that in those port cities, the war empowered gay men not only because they had the opportunity to have sex with other men, but because of their relations with heterosexual men in particular. D’Emilio pointed to the experience of Donald Vining, a noted gay diarist who lived in New York City during and after the war.

“Many of the non-gay men with whom Donald Vining enjoyed physical intimacy during the war resumed a heterosexual existence in peacetime, but the occurrence of what, for them, was an unusual homosexual encounter intensified for men like Vining the sense of being gay,” he said.

That thriving wartime queer community remained, even after much of the world had returned to peacetime. In New York, the Veterans Benevolent Association was founded in 1945; it was a social club for gay ex-servicemen, D’Emilio wrote, that held parties for hundreds of men who were previously stationed in the city.

Of course, the war and its aftermath wasn’t all fun and games. Frank Burton, who told his story under a pseudonym to the Oberlin College Lesbian, Gay, Bi and Trans Community History Project in Ohio, said that being gay during the war was stressful. After all, the Canadian and American armies, air forces and navies all officially rejected homosexuality as something unbecoming of an officer.

“Back in those days, I think a lot of people felt the tension and so forth of leading a double existence [and] drank a lot,” Burton said. “I was a heavy drinker, for years. And most of the people I knew were … [You] would find somebody that [you] felt compatible with, you’d go out and drink yourself silly, and you’d end up in a room together.”

The Canadian conscription crisis of 1944 interrupted the homosexual witch-hunt that was, until then, being carried out by commanding officers, psychiatrists and snitches at home and abroad. But being discovered as gay was still something that earned a soldier a dishonourable discharge.

Jackson said gay officers in the Canadian military faced court martials and were often charged with “scandalous behaviour unbecoming the character of an officer” or “conduct to the prejudice of good order and military discipline.”

Jackson wrote that military officials argued — and in some cases, still argue — that “the presence of openly homosexual soldiers would disrupt unit cohesion. Queer soldiers would be a disturbing influence, weakening the bonds that hold a group together and making it less effective.”

Outside the context of outright discovery, gays were often simply ignored — a position that has regrettably extended to much of the literature about the war. Take Paul Fussell, for example, who wrote The Great War and Modern Memory in 1975. He practically denied that any real queers served on the front lines; instead, he framed homosexual activity as “temporary.”

“Given the deprivation and loneliness and alienation characteristic of the soldier’s experience … we will not be surprised to find both the actuality and the recall of front-line experience replete with what we can call the homoerotic,” he wrote.

“I use that term to imply a sublimated form of temporary homosexuality. Of the active, unsublimated kind, there was very little at the front.”

Not so, says Jackson. Gay sex and intimacy were often tolerated by soldiers on the ground. Solidarity among men on the front lines — both gay and straight — often trumped any pre-war prejudice or bigotry that might otherwise have caused divisions.

“There were secrets everywhere, and soldiers protected each other from [their superiors] in the army, navy and air force. It was to everyone’s benefit to protect the unit,” Jackson said.

In her research exploring cross-dressing and military entertainment in the Second World War, Laurel Halladay found evidence supporting that quid pro quo approach. She wrote that “available documents on military entertainment” never mentioned homosexuality as being a problem. She attributes that to “a more flexible cultural environment at that particular time and place, one created by the absolute necessity of group cohesion for survival.”

Jackson added that, off the front lines, society hit the pause button on morality. He said that men and women, both overseas and at home, forgot all about pre-war norms.

“War was like suspended animation. Social bonds were broken down,” he says.

Jackson described the gay underground of wartime London as but one example of men forgetting all about their preconceived sexual boundaries. “Soldiers were selling their bodies in London,” he said. “Older British men with money took advantage of younger, handsome men from the colonies.”

After the war, Jackson said, Canadian society embraced a return to pre-war normalcy. There was a sense that Canadians needed “to put society back together again,” he said.

But University of Toronto political science and sexual diversity professor David Rayside said that, at a broader level, the Second World War had a dramatically progressive effect on post-war social norms and policymaking.

“The Second World War was total war, which made it different than other wars. It entailed huge levels of mobilization,” said Rayside. “It created huge avenues for social change. Wars of that scale generate expectations for massive progressive change afterwards.”

Rayside said although Canadians tend to remember a period of conservatism following the war, that perception is misguided.

“The post-war period was not conservative,” he said, referring to a greater focus on human rights and gender issues after the war, as well as the emergence of radical beat poetry and lesbian pulp fiction.

“The seeds of change didn’t just disappear.”

Illustrations by Ken Boesem.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra