Minister of tourism and associate finance minister Randy Boissonnault says that he hears the calls for Canada to have a special envoy for 2SLGBTQI+ issues internationally.

“Canada should have an envoy,” Boissonnault declares. When asked about the response to this demand from around the cabinet table, Boissonnault smiles and taps the table in front of him. “Stay tuned. People get it—it needs to be done in the right way, at the right time, but I’m very encouraged about the fact that the community has asked for this. There are a lot of voices that have said we need this.”

In a wide-ranging interview with Xtra, Boissonnault started off talking about the years he spent trying to hide who he was.

“I spent 30 percent of my mental energy trying to be a straight guy, and when I stopped that, I got to be 100 percent me, and I’ve never looked back since,” Boissonnault says. “When I was growing up in Ralph Klein’s Alberta, there was no chance of a queer kid being an MP, certainly not as a Liberal and certainly not as a queer Liberal, but the world changed.”

Boissonnault credits Scott Brison crossing the floor to the Liberals in 2003 as the first time he looked at Parliament and thought that maybe a career in politics was possible, and it confirmed for him what party he belonged to.

“I didn’t expect I would be in a country where I could marry my partner, because it was unthinkable back then,” Boissonnault says. “Alberta changed and Edmonton changed, but we can never stop being vigilant.”

Boissonnault was first elected in 2015, and in 2017 was made Special Advisor to the prime minister on LGBTQ2S+ issues. He lost his seat in the 2019 election, which he describes as his “sabbatical” before being re-elected in 2021, at which point he was appointed to cabinet in his current portfolios.

During that time out of office, Boissonneault helped to create the Global Equality Caucus, an international network of parliamentarians and elected representatives dedicated to tackling anti-LGBTQ+ discrimination, alongside other out politicians like Nick Herbert from the U.K. and Angélica Lozano Correa from Colombia. The impetus was the sense of frustration from being queer MPs and senators who would only meet along the margins of other conferences and events, before deciding to make their own group.

“It was an important thing for me to work on during my ‘sabbatical’ from Parliament,” Boissonnault says.

When asked about the progress around issues raised when he was Special Advisor, Boissonnault lists banning conversion therapy and progress on lifting the blood donation ban as things he can check off his list.

“I’m not happy with what’s coming up from Florida and other parts of the States—the DeSantis rhetoric and hate is not helping anybody,” Boissonnault says. “What’s the big deal about a drag queen reading a book at a library? People need to get over themselves. Gender non-binary people have a place in our society, and people need to stop worrying about each other’s business, maybe get off of Facebook, and walk a mile in somebody’s high heels.”

Boissonnault also says that he learned from France and the U.K. and that their action plans for local queer and trans issues spurred the creation of Canada’s, and the birth of the 2SLGBTQI+ Secretariat, which is now growing.

“We were able to lay track down for the 2SLGBTQI+ Action Plan and the $100 million down payment, and I can tell you, being associate minister of finance, this close to that shop as a queer person means that I get to have an eye on things, and I also get to advocate, which I did, and I will continue to,” Boissonnault says.

Boissonnault says that being around the cabinet table means he gets to raise the communities’ issues, and says that there is a lot of solidarity around that table.

“There are a whole bunch of us that didn’t have voices 10 years ago, and making sure that minority community voices are not just heard but are present and shaping policy makes a big difference,” Boissonnault says. “The face of government has changed since we’ve been in office.”

Boissonnault also says that internationally, he gets a chance to either thank other countries for the work they’re doing or have a conversation about doing more, which gives him insight into when a government feels wedged or it hasn’t moved fast, which helps him to understand how Canada can help them.

“There is a huge international world out there, and not everything can be done by governments,” Boissonnault says. “Some of the change has to come from the citizenry, and that’s where actors like the United Nations Development Program matters, the Westminster Foundation for Democracy matters, and the fact that we have envoys, like the United States and the United Kingdom has a special envoy—Canada should have an envoy.”

Boissonnault says that such an envoy needs to be a full-time job, speaking from the experience he had when he was Special Advisor while also doing his work as an MP.

“You need that full-time lens, and Jessica Stern in the U.S. is remarkable, and she ran Outright International before President Biden named her,” Boissonnault says. “It is about being around the world and being present, and also engaging the corporate sector. How many Canadian companies are in-field making sure that LGBTQ+ people are protected in those communities?”

Boissonnault says that this is happening with some U.K. companies and a number of U.S. companies, and should be happening with Canadian firms.

Boissonnault also points to pots of money that Canada provides internationally, such as to our embassies and missions abroad. One example was how the Canadian mission in Ecuador used $25,000 to help a local group helping queer people fleeing Venezuela when the local government wouldn’t help, and that grew into an organization that now spans four countries in the region.

“That’s what I want to see this envoy doing around the world,” Boissonnault says. “Set a baseline, set some targets, empower the missions to do that work.”

Boissonnault points to money provided to groups like equality and social justice educators Equitas as driving change in communities around the world, as proof that Canada can do more.

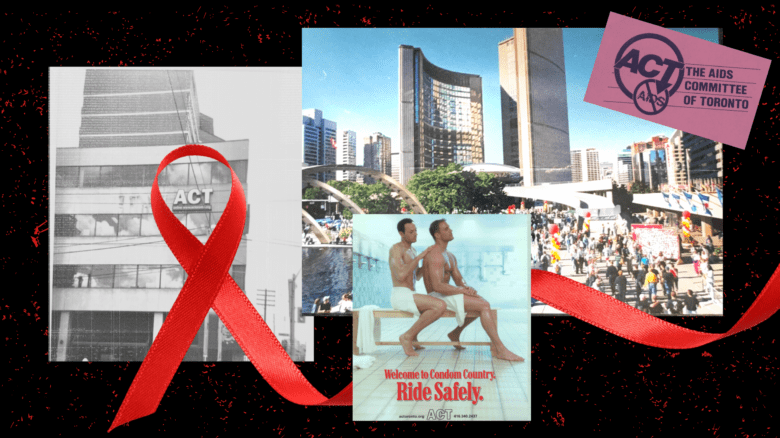

With regards to the tourism part of his portfolio, Boissonnault points to the fact that more than 10 percent of the world’s Pride festivals happen in Canada, which is an economic driver and important for the politicians to show that they care about the queer and trans communities, but also gives them an opening to engage with the communities.

“Queer tourism for me is a big deal,” Boissonnault says, and notes that it’s not just about Pride. “LGBTQ2S people want to go to the Jazz Festival and to Stampede.”

It’s not only tourism, but ensuring that the government does things like ensuring that queer and trans people are present in trade missions.

“I want allies, but the community needs champions,” Boissonnault says. “Allies will have your back when you’re in the room, but I want people to have my back and the community’s back when we’re not in the room, and that’s the difference between an ally and a champion. And we’ve developed champions.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra