For the past two years, Nilay Joshi has been doing drag performances across India under the name of Miss Bhenji—something he feels only became possible after Sept. 6, 2018, when the Supreme Court of India struck down Section 377, the colonial-era law that criminalized homosexuality. “People have now started to accept me and love me for what I do,” Joshi says via Skype from his home in Nagpur. “I mean, some people still have problems, but the amount of love just suppresses it.” But Joshi’s story is the exception. The legal framework in the country may have changed, but that’s meant little in the day-to-day lives of queer and trans Indians. Most members of India’s LGBTQ+ community still face challenges, and the COVID-19 pandemic has only made matters worse. Many queer individuals have been forced to live with unsupportive or homophobic family members, while poorer queer and trans folk are contending with increasing financial struggles and the decimation of the few LGBTQ+ safe spaces. A 2019 report by the International Commission of Jurists, a non-governmental organization, found that LGBTQ+ people in India face discrimination due to their real or perceived sexual orientation, gender identity and gender expression. The discrimination further “affects their ability to fully enjoy their civil, cultural, economic, political, and social rights.” The report also found that trans and intersex people face severe forms of discrimination and violence. “Accounts of bullying in schools were common. Educational and training opportunities are often denied to LGBTQ persons due to harassment, bullying, and violence,” the report states.

Community organizer Shyam Konnur in Bangalore. Credit: Courtesy of Zoom.

For Shyam Konnur, the founder of Mist, a queer and trans arts collective based in Bangalore, overturning Section 377 hasn’t amounted to much. “You are allowed to have sex,” Konnur says. “It’s nothing, nothing else.” Konnur, who won the Mr. Gay India pageant earlier this year, feels decriminalization is a far cry from protecting rights. “There’s no act that says you’re not supposed to discriminate against an LGBTQ+ person,” he says. And that discrimination is clear when it comes to marriage and adoption. Same-sex unions remain illegal in India: In a recent court hearing in the Delhi High Court, the government of India opposed a petition to recognize same-sex marriages. (Two additional marriage cases are currently making their way through the system and are expected to appear before the court early next year.) Same-sex couples are also prohibited both from adopting in India or, after the Surrogacy Regulation Bill that passed last year, enlisting the help of a surrogate.

“There’s no act that says you’re not supposed to discriminate against an LGBTQ+ person.”

India’s trans and intersex communities are unique. Traditionally known as hijras, this group of eunuchs, cross-dressers, intersex and trans people has been revered in Hindu mythology and received legal recognition under a separate “third gender” category six years ago. But their position in society is incredibly tenuous. Ostensibly, the Trans Rights Bill that passed in 2019 was supposed to safeguard the constitutional rights of India’s trans community, but it was drafted without any community consultations. The bill provides social welfare benefits such as a pension, housing and food to recognized transgender individuals—but makes the procedural path a difficult one by requiring proof of sex reassignment surgery (SRS). “The Trans Rights bill was a horrible bill,” Konnur says. “We’re still fighting against it. The first agenda, after COVID-19, will be to send the suggestions to the government.” Moreover, most hijras don’t have a government-issued ID, making access to basic amenities difficult. Konnur says that hijras have to beg or get pushed into sex work just to put food in their mouths; many trans individuals face stigma and systematic exclusion in education and employment. “They earn maybe 100 or 200 INR [approximately $3] a day through begging. Now, the bill has made SRS a compulsion, which costs 80 to 90,000 INR [$1,600],” Konnur says. “The pandemic has made even their access to food impossible, let alone these expensive procedures. Not to generalize, but most of them are living in a bad state, areas that might be in coronavirus containment zones.” COVID-19 restrictions have amplified these problems and made it more difficult for hijras to be on the streets as beggars or sex workers.

Psychotherapist Sayli Jadhav in Mumbai. Credit: Via Zoom.

Sayli Jadhav, a psychotherapist living in Mumbai, shares Konnur’s outrage. “The Trans Rights Bill in itself is so transphobic, and there was no support for it,” Jadhav says. “It’s [made life] so much harder for [trans and intersex people].” Jadhav, who works with queer and trans clientele, notes that generations-old perceptions that link hijras with the sex trade are hard to shake. People consider the community to be hypersexual—and taboo. “When your identity gets reduced to your sexual orientation, people just see you [only] as a sexual being,” she says. “It’s problematic.”

“The Trans Rights Bill in itself is so transphobic, and there was no support for it.”

Jadhav, who identifies as pansexual, has faced derogatory remarks herself. “They say, ‘You’re like a half boy,’ and men keep asking if I want to have a threesome with them.” She has heard these sorts of comments from within the medical establishment, too. “My doctor questioned me once, saying I am probably looking to date women as I had bad experiences with men.” Society at large—and even other LGBTQ+ people—understand little when it comes to the differences between drag queens and trans folks. Like Jadhav, Joshi is often confronted by people who question his gender. “They have this image that a drag queen should be in a certain manner only, like just dramatic,” he says. “I wasn’t fitting in that box. I was being quirky, funny and just myself, being a complete weirdo. And they had problems with it.” Jadhav adds that, as the COVID-19 pandemic continues, the state of mental health within the LGBTQ+ community is of critical concern. “There is an increasing feeling of anxiety and identity confusion in the community,” she says. “They’re being forced to live with their families and deal with the toxic violent environment everyday.” “There is a lot of stress,” Konnur says. “Many face mental pressure, peer pressure. Especially now, during COVID-19, we are receiving more calls from people seeking help. We receive calls on how people are being outed, as they are living with their families, and their phones have been accessed.” While his organization, Mist, is doing what it can, there has been little support from the government. “The government is saying, ‘We are letting you breathe. What more do you want? We will not kill you, but we’re not going to make this easy for you either,’” Jadhav says. Konnur agrees. “Leaving ideologies, left or right, aside, I don’t think the government is doing anything. They have done nothing at all so far,” he says. “I learned one thing about the current government: They just ignore.” Narendra Modi’s government, led by the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), has sown division in the country by undermining the rights of the minority Muslim population and other groups. That polarization is evident within the LGBTQ+ community. “The community is literally divided into the right and the left,” Konnur says. “Within the community, you have people shaming one another on their political inclinations.” He worries that such divisions will decimate the few safe communal spaces available for queer and trans people, like the ones run by his organization, university safe spaces and parties like the drag nights at the LaLiT Ashok hotel. Most of these safe spaces are confined to the metropolitan cities of India. Rural areas and smaller towns offer few respites from the stigma that LGBTQ+ folks face. Honour killings have been a regular practice in many parts of India, driven by a culture that approves of anti-gay violence. More safe spaces for the community are therefore essential, Jadhav says. “People need people who can understand, validate and affirm their experiences and have access to these spaces when they reach out for support.” Jadhav hopes that education can bring further change. “There isn’t comprehensive sex education happening anywhere. It’s like a systemic issue,” she says. “While it might be very difficult to change this with adults, with the coming generation, I think education is a way to go.”

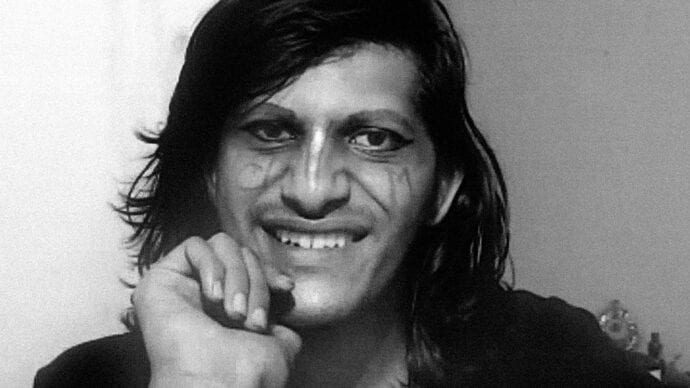

Drag performer Nilay Joshi in Nagpur. Credit: Via Skype.

Joshi puts the emphasis more on collectivism. He points to young people who are increasingly coming together under the banner of Pride. “Most of us drag queens are also LGBTQ+ activists who are trying to make a change. Since Section 377 has been removed, more and more people want to consciously learn about the community,” Joshi says. “I wish someday [to] have my own TV talk show where I can employ all queer folks. I know it will take a lot of time for India, but I [see] the strength in our community. It’s difficult, for sure, but not impossible. I know.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra