It’s a beautiful late July day when the small crowd gathers at Church and Wellesley, the intersection at the heart of Toronto’s Gay Village. Some wave small rainbow flags; others brandish simple pieces of cardstock bearing messages in no-frills text: “Give us back our community centre,” reads one; “The 519 is an enabler,” says another. Protest organizers hold microphones, sporting yellow T-shirts emblazoned with the slogan: “Takes a village to save the Village.” The crowd of mostly middle-aged men moves one block west to Yonge Street and marches into the street, occupying the northbound lane as they walk up to Bloor, holding their signs proudly over their heads. “Remove the violent few” is scrawled hastily in big, blocky letters on a man’s neon-green poster.

This isn’t some kind of anti-homophobia demonstration, despite the location and presence of rainbow flags. They’re local residents and business owners frustrated with the presence of unhoused people in the neighbourhood, particularly around Barbara Hall Park, which sits adjacent to long-standing LGBTQ2S+ community centre The 519. In speeches and interviews given to journalists, protest organizers and attendees raised concerns about the visibility of drug use, instances of vandalism and harassment and feelings of a lack of safety. A key point of contention was The 519 and the community services they offer to the unhoused. Though the call to action was an even-keeled request for all levels of government to “find concrete solutions,” the overall tone was clear: they want the unhoused gone. “It affects residents, it affects business, it affects tourism. This is supposed to be a live and vibrant community and people are scared to walk up and down the streets now,” Steve Dawson, owner of Dudley’s Hardware, a local business that’s been on Church Street since 1934, told the CBC during the protest.

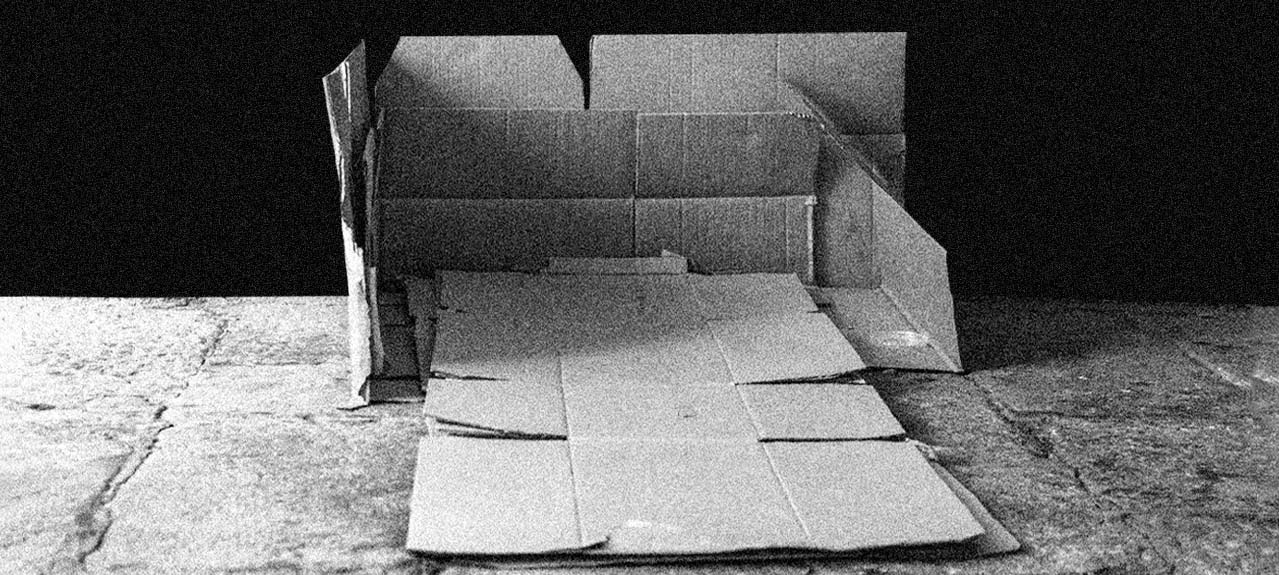

A homeless encampment near Toronto’s Gay Village. Credit: Colin Perkel/CP Images

Over in Montreal, the situation is much the same. On Rue Sainte-Catherine around Metro Berri-UQAM, where the Gay Village is loosely concentrated, the presence of unhoused people and visible drug use has resulted in rising tensions with local business owners. Merchants advocated for the city to find solutions prior to Pride in August—traditionally a boon for local businesses; in June, an increased police presence was dispatched to the area. La Société de développement commercial du Village, the neighbourhood merchants’ association, has long called for the neighbourhood to be made more “family-friendly” and hospitable to tourists, to the point of attempting to blanch the association with the LGBTQ2S+ community and rebrand from “Le Village Gai” (The Gay Village) to “Le Quartier Inclusif,” or The Inclusive Neighbourhood. The visible presence of poverty and precarity doesn’t align well with this vision of gentrification. “When people pass by here and see people asking for money, asking for cigarettes, they don’t want to come here anymore,” Emily Yu of Sainte-Catherine’s Yamato Dumpling said to the CBC in June.

These rising tensions in the Gay Villages of Canada’s two most populous metropolises and elsewhere raise larger, pressing questions: about what purpose these neighbourhoods serve; about who’s included—and who’s excluded—when queer and trans people think and speak about our communities; and about our perceptions of what’s appropriate and what isn’t in public life. The unprecedented and urgent crisis of homelessness currently facing cities across North America certainly requires addressing—and everyone, housed or unhoused, deserves to live without exposure to, or fear of, violence and harassment. But this crisis is not one that will be solved by excluding the voices and wishes of those most impacted by it, or by othering those who in fact live in and are a part of our communities, regardless of the state of their housing. At this crucial moment, we have an opportunity: to radically reimagine what kind of Village we want to have, and what we want it to stand for.

In August, during Montreal’s Pride Month, I found myself walking along Rue Sainte-Catherine. The street had turned pedestrian-only for the summer, and was filled with a mass of people walking leisurely between the gazebo-covered booths that flanked the road: banks and cellphone companies professing their queer solidarity, middle-aged lesbians representing the Quebec Lesbian Archives, the Canadian army and Montreal police force looking for butch recruits, community health workers handing out free condoms. I couldn’t get over how different the street was than usual. In previous months, I’d typically walk on to Sainte-Catherine to find a bustling community of unhoused people: sitting on the side of the road chatting with one another or panhandling, pushing crowded carts down the street, sometimes being questioned by stone-faced police officers standing in power stances. On this day, it was as though they’d more or less disappeared into thin air. Though the city didn’t release any statements detailing the outcomes of the increased police patrols, and it’s unclear exactly why the unhoused had left, it seemed that the city had, ostensibly, succeeded at quietly clearing the street for Pride.

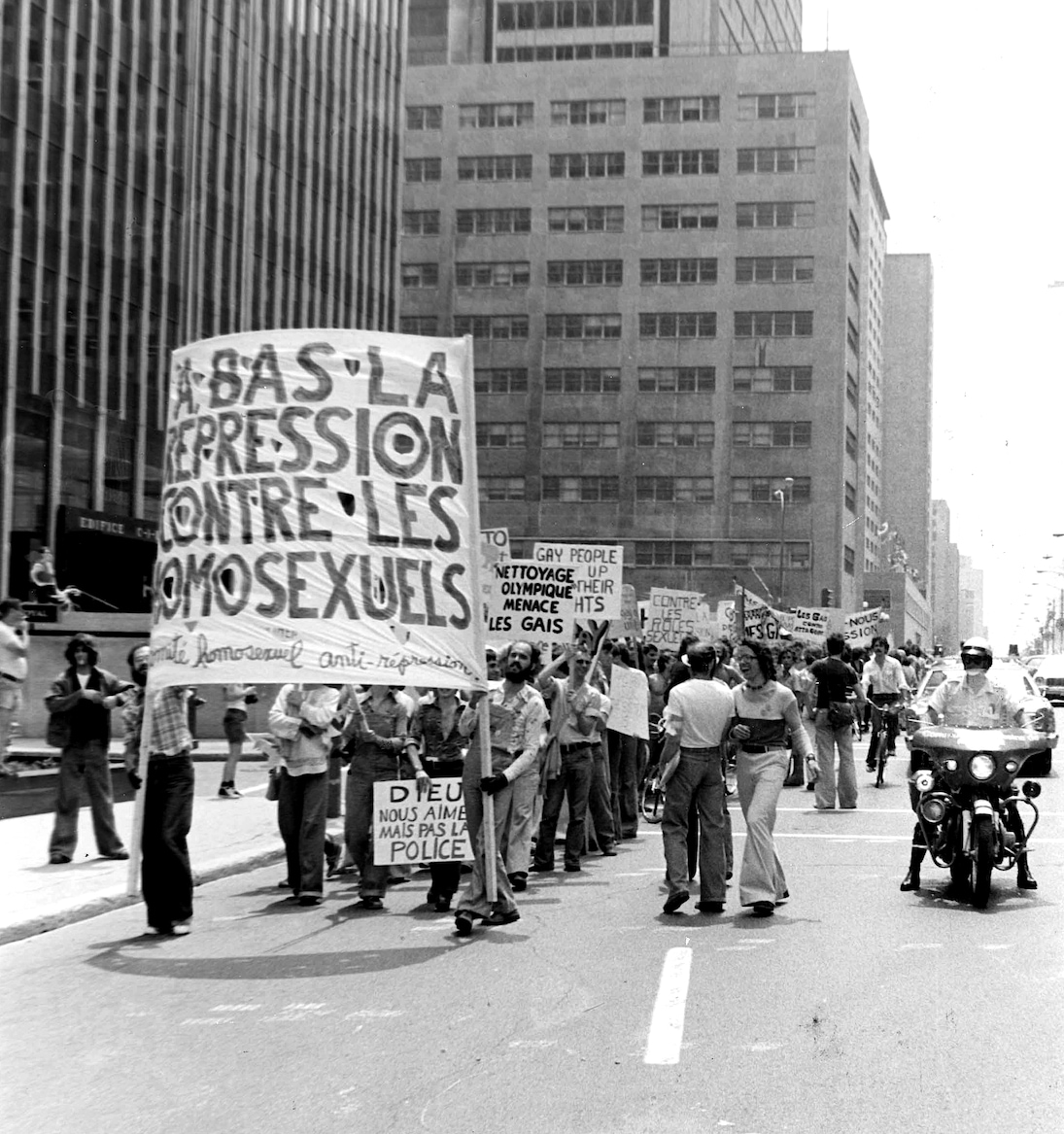

The scene brought to mind a piece of Montreal history. In 1976, the Summer Olympics were to take place in Montreal—the first time they would be on Canadian soil— and then mayor Jean Drapeau wanted to get his city ready for all the international attention. Between 1975 and summer 1976, Montreal police initiated a series of violent raids on lesbian and gay bars and bathhouses, arresting dozens of people and spreading intimidation through the community, in a spree referred to as the “Olympics Cleanup.” Similar raids took place in Ottawa and Toronto on a smaller scale; the overall intention was to prepare the country for the influx of tourists by getting rid of the “unsavoury” elements of public life. This wasn’t Drapeau’s first time attempting to rid public spaces of expressions of queer life; in the 1950s, he infamously launched a campaign of deforestation on Mont Royal, an infamous cruising spot, wanting to remove hiding spaces that could be used for “immoral” activities like drinking alcohol or having gay sex. The removal caused sustained environmental degradation to the point of the mountain earning the ironic nickname Mont Chauve—Mount Baldy.

In June of 1976, demonstrators rallied against the Olympic cleanup campaign in Montreal that saw lesbian and gay bars raided by police and gay bathhouses closed. Credit: Courtesy of the Arquives

When the Olympics Cleanup happened, Montreal’s Gay Village was located much farther west than it is today, concentrated around Rue Stanley in the downtown area. In the ’80s, there was an exodus of gay businesses eastward, to where the Gay Village currently is. There were a variety of factors influencing this move, including the targeting by police and pressure from developers as the downtown area gentrified, as urban geographer Donald W. Hinrichs detailed in his 2012 book Montreal’s Gay Village: The Story of a Unique Urban Neighborhood Through the Sociological Lens. When the new Village began to establish itself, it did so in one of the city’s most impoverished areas, racked by systemic deindustrialization and disinvestment. LGBTQ2S+ people and businesses found a home there, on the outskirts of the city where they could be left alone, without being harassed by a majority population that disagreed on what things were appropriate parts of public life.

Ideas around what’s acceptable in public life have certainly shifted over the last 40 years. Today, gay bathhouses and queer bars enjoy public-facing presences on Rue Sainte-Catherine; in 2017, Montreal even issued a long-overdue apology for the history of police targeting and raids against the queer community. In other ways, things are much the same. The city still polices the Gay Village, seeking to sweep unsavoury elements under the rug; and although norms have changed, it’s still those with power who get to decide what is and isn’t permissible. Outward expressions of poverty and precarity—panhandling, intoxication, sleeping on benches, in tents and on sidewalks—need to be removed from public sight, lest they impact the comfort and spending habits of tourists and higher-income residents. Though the targets may have shifted, in some ways the philosophy behind the Olympics Cleanup still lives on in today’s Gay Village. It’s a philosophy we need to root out if we want our Villages to be communities grounded in principled inclusivity and humanity, places that serve as shining examples for addressing the homelessness crisis with compassion and strength.

Our current crisis of homelessness did not crop up out of nowhere. It’s been a long time building, spurred by multiple factors such as increasing housing unaffordability, the inaccessibility of adequate healthcare and increasing drug toxicity, and then the compounding system-wide stressors of the pandemic and inflation. From May to September this year, the average asking price for a new rental in Canada increased by over $100 each month. As of September, this average is $2,149; if you wanted to spend 30 percent of your income on rent, you’d need to be making $85,960 a year after taxes, significantly more than the actual median after-tax income of $68,400. Meanwhile, more and more Canadians are unable to access healthcare; according to a 2023 survey by the Angus Reid Institute and the Canadian Medical Association, half of Canadians either don’t have a family doctor at all, or struggle to get an appointment with one. Finally, an increasingly toxic drug supply—in which nearly 23,000 Canadians died from opioid toxicity between 2016 and 2021—coupled with our overtaxed healthcare system, is creating worse outcomes in regard to substance use, and not just in terms of treatment for drug users. If you’re unable to get adequate care for a chronic health condition using the typical routes, for example, you’re more likely to turn to other sources for pain relief.

“An overwhelming number of the unhoused are, in fact, LGBTQ2S+ people.”

Poverty, poor health and addiction are all factors that influence homelessness, so it’s unsurprising that we’re seeing more people pushed to the streets during this infrastructural degradation. The City of Montreal’s 2022 census found that the number of visibly homeless people in the city—which doesn’t reflect the actual total number of homeless people—was 4,700, a whopping 33 percent increase from just four years earlier. While the numbers in Toronto have actually decreased from 2018 to 2021, the number of asylum seekers forced to sleep on the street in front of shelters due to lack of space this past summer indicates an increasing problem.

In the midst of all this, our shelters and community services are overburdened by the overwhelming need. “We’re full all the time. We have to refuse people because all of our beds are already occupied. The amount of refusals has gone up,” says Marie-Pier Therrien, communications director at Montreal’s Old Brewery Mission, a long-standing homeless shelter. “The stays at our shelter are longer, and the complexity of the cases is increasing, because there’s a lot more precarity when people come to see us.” It’s the same in Toronto: in June, the city’s shelters turned away approximately 273 people each night due to lack of capacity—the highest number ever recorded.

During the July protest in Toronto, protestors repeatedly called for The 519 community centre to stop servicing the unhoused population, insisting that it’s too much for them to handle. Dawson, the hardware store owner, told the CBC during the protest that the centre isn’t supposed to be social-services-oriented, and that it isn’t equipped to deal with complex issues like drug addiction. In some ways, The 519 agrees that the homelessness crisis is bigger than what they can handle. “The need for services is huge, and impacted by much larger systems than The 519 is able to influence,” says Martha Singh Jennings, director of housing advocacy and support services at The 519. But that doesn’t mean they should just give up, and pull away from a population that urgently needs access to services.

Singh Jennings notes that inclusion of the unhoused population has always been a part of The 519’s programming; the centre’s founding documents from 1975 note that there’s a large unhoused population in the community, and that they want to ensure that those people are included in service provision. “It’s our mandate to respond to community needs, and folks who are in the area are our community,” says Singh Jennings.

An overwhelming number of the unhoused are, in fact, LGBTQ2S+ people. “The folks we interact with in and around The 519, many of them are queer and trans,” says Singh Jennings. The City of Toronto notes that 12 percent of people experiencing homelessness in the city are LGBTQ2S+ people, and 26 percent of homeless youth; in Canada, only four percent of the general population aged 15 and older identifies as LGBTQ2S+. Queer and trans people in Canada are more than twice as likely to experience homelessness or housing insecurity at some point in their lives. The idea that the unhoused people in our Villages are somehow separate from our communities doesn’t hold up under the reality that homelessness is, overwhelmingly, a queer issue, and should be treated as such—not pushed out of our communities by police and frustrated business owners.

Credit: Getty Images; Elham Numan/Xtra

The homelessness crisis is complex and multifaceted, and will be solved only by collaboration between all levels of government, service providers and the community. People already doing work with the unhoused community say that adaptive, one-to-one services that respond to people’s actual needs, rather than imposing standardized initiatives on them, is the best route of action. “We’ve been advocating for a task force with mental health experts, community experts and addictions experts with a holistic approach, to understand what services they need and start to identify the best next step,” says Therrien.

“It’s going to start by being present.” says Steffes Lavoie, an outreach worker at Dans la rue, an organization in Montreal that supports unhoused youth. There needs to be better trust in, and communication with, current service providers doing on-the-ground work, Lavoie says. “Outreach workers actually take the time to know the people and give help, and not just force it on them.”

An increased police presence isn’t productive for improving relationships with the unhoused and helping them feel safe and supported. “They don’t feel at ease at all [due to the increased police]. They end up being arrested for jaywalking sometimes,” Lavoie says. Therrien notes that it can come down to the type of approach that the police take: “Bringing homeless people into the police station isn’t going to solve anything.” She adds that the Old Brewery Mission is involved in consultations with the Montreal police, and that they encourage the use of “mixed teams,” or police dispatches that involve other professionals, such as social workers or mental health professionals.

Several of these teams are already being used in Montreal. Police and community services collaborate with Urgence psychosociale-justice, or crisis and mental health support teams, who are trained to respond to crisis situations in place of police units. There is also the Équipe mobile de médiation et d’intervention sociale, a pilot project in certain Montreal neighbourhoods, in which a team of social workers are dispatched for crisis mediation in place of police. In Toronto, a similar Toronto Community Crisis Response Program was formed in 2020 in response to calls for police reform, in which teams of trained mental health professionals are dispatched instead of police for crisis intervention.

Nonetheless, crisis response teams are only reactive in nature. Though they won’t worsen the situation, like criminalization will, they also won’t entirely solve anything. The homelessness crisis requires a diversion from policing to more community-focused models—as well as better drug testing and safer supply alternatives, and more addiction and mental health services. But at its core, it requires one thing: more housing, and housing that’s materially accessible to those living in precarity. Last year, the Old Brewery Mission opened a 12-unit housing project, Les Voisines de Lartigue; Therrien notes that they found that the previously unhoused women residents really stabilized their lives and began reintegrating into society once in their own homes.

A homeless person sleeps on a city bench in Montreal. Credit: Graham Hughes/CP Images

In places that have made real strides in tackling homelessness, housing has been the key. Over the last decade, Houston, the U.S.’s fourth-most populous city, moved over 25,000 people into housing, leading to a 63 percent reduction of unhoused people in the region since 2011. The overwhelming majority of them remained housed after two years. Previously, the city had one of the highest per capita rates of unhoused people in the country. The idea behind Houston’s success is known as the Housing First approach, in which unhoused people are moved straight into apartments, without first requiring them to become employed or sober or meet other qualifications first. A 2014 study by the Mental Health Commission of Canada followed 2,000 unhoused people across five Canadian cities for two years, approximately half of whom were treated with a Housing First approach, and the other half given access to existing shelter and mental health treatments instead, what’s called the Treatment First approach. By the end of the study, 62 percent of the Housing First group were housed all of the time, as opposed to just 31 percent of the Treatment First group.

Housing First clearly works—but in order to implement it in Canada, we need a lot more affordable housing. There are some gains being made: after Olivia Chow became mayor of Toronto this summer, she announced a top-up of the Canada-Ontario Housing Benefit, one of the few ways that unhoused people are able to obtain money for housing. The HousingTO Action Plan also intends to build 65,000 affordable housing units by 2030. To accomplish this aim, and more, the city needs the collaboration of the provincial and federal governments. Given that both higher levels of government did provide temporary higher funding during the summer’s asylum-seeker housing crisis, things seem promising, though only time will tell.

In Toronto, Montreal and other big cities in North America, solving the homelessness crisis will require the collaborative implementation of affordable and supportive housing under a Housing First approach. But in the meantime, we need to ensure that the unhoused people in our communities aren’t alienated and erased from the neighbourhoods that they’re a part of. To reduce the tensions in our Villages, Singh Jennings says we need “more conversation and collaboration,” as well as “concerted efforts from all involved to not ‘other’ people.

“One of the reasons people gravitate to queer and trans spaces is because they’re warmer, safer, more humane spaces,” she adds. “Because we’ve had to create those spaces for ourselves, they’re more accepting, safer and more comfortable of many different identities and experiences.”

At the end of the day, we can’t change reality: unhoused people live in our Gay Villages. The only choice we have is whether or not we treat them as part of our communities. “You cannot just move the homeless population somewhere else,” says Therrien. “You can’t say, ‘We have a big space in [the Montreal borough of] Anjou, how about we bring you there?’ They’re not gonna go.”

Our Villages were created as inclusive, liberal enclaves within hostile cities in which the marginalized could live as their authentic selves among a community of accepting neighbours. This is an ethos that we can continue to align ourselves with, by treating the unhoused people who live in our communities with humanity and inclusivity—or it’s one that we can abandon, by instead prioritizing the desires of tourists, business owners and higher-income families. During this crisis, our Villages sit at a crossroads of identity; it’s up to us to choose in what image we’ll shape them.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra