In the streets of Rio, a mixture of hope, samba and fear accompanies the ongoing election campaigns that seek to oust conservative president Jair Bolsonaro. Election stickers with rainbow flags and promises of a path forward—something LGBTQ+ Brazilians haven’t experienced in the four years of Bolsonaro’s far-right reign—are desperately and joyfully handed out to potential voters. On October 2, Brazilians will vote for the kind of country they want: a reactionary, violent dystopia, or a nation that offers a glimmer of progress.

In the runup to the election, LGBTQ+ activists have been mobilizing to increase queer and trans representation in federal and local governing bodies. Voters will be choosing a president, a vice president and national congress members, as well as local positions such as state senators, governors and vice governor. LGBTQ+ candidates are hoping that popular resistance to the current conservative government will propel them to power. On September 7, for example, in honour of Brazil’s independence day, people took to the streets in the tens of thousands in several capital cities to protest the growth in hate crimes against the community during Bolsonaro’s term. An opposition march I attended in Rio de Janeiro on September 25 saw thousands of people coming out in support of leftist candidates. The event was led by grassroots carnaval groups and repeated in several cities like São Paulo, Brasília, Salvador, Belo Horizonte, Recife, Olinda, Vitória and Belém.

“We have no time to waste and nowhere to run.”

VoteLGBT, the Brazilian NGO seeking to increase LGBTQ+ representation in the country’s political system, has observed a 36 percent growth in the number of LGBTQ+ candidates since 2018, the year where President Bolsonaro was elected. There has also been a 44 percent rise in the number of trans candidates compared to 2018, according to a report by the National Association of Travestis and Transsexuals (ANTRA). At last count, 76 trans candidates are competing in local and federal elections. The majority of these candidates stand for progressive causes: 85 percent of candidates are running in progressive parties such as the Workers’ Party (PT) and the Socialist and Liberty Party (PSOL).

A goal shared by most LGBTQ+ candidates is to increase queer and trans representation so that pro-LGBTQ+ policies have a better chance at being drafted and put into action. In Bolsonaro’s Brazil, that’s a tall order. Roberta Cassiano, a philosophy professor at the Federal Institute for Education, Science and Technology in Rio de Janeiro, and founder of the lesbian magazine Brejeiras, says many LGBTQ+ voters do not trust government institutions and party politics.

Credit: Silvia Izquierdo/AP Photo

“When LGBTQ+ resistance articulates itself on a cultural level, separated from party politics, mobilization is easier,” Cassiano explains. “There is a certain general climate of distrust in the institutional system—which I consider a serious mistake and a huge danger for all of us in the community.”

Cassiano has been working on the campaign for feminist Black lesbian journalist Camila Marins, a Workers’ Party candidate running for the national congress. This is part of Cassiano’s focus to bring LGBTQ+ people into politics and rehabilitate the image of institutional politics within the community.

“I tend to believe that the main goal of all LGBTQ+ candidacies, including the one I am currently involved in, is to affirm [institutional] politics,” Cassiano says.

Despite the historical exclusion of queer and trans people from politics in Brazil, Cassiano says that LGBTQ+ Brazilians have to take up space in the political arena to advocate for their communities—because nobody else will.

“We must dialogue with our side and show that without fighting for political space, we will always be put aside by our comrades on the left or we will be literally annihilated by the right. We have no time to waste and nowhere to run.”

“A society that is safe for an LGBTQ+ person will also be safe for those who are straight and cisgender.”

For Sara Azevedo, a lesbian Socialism and Liberty Party candidate running for senate in the state of Minas Gerais, taking space in institutional politics means making sure LGBTQ+ political campaigns are not solely identity-based, but inclusive of the issues faced by the majority of Brazilians under Bolsonaro: 10 million Brazilians are unemployed and forced to deal with one of the highest rates of inflation in the world. Those economic realities, Azevedo says, encourages hatred of minorities and other vulnerable populations.

“We have to explain to people that we are not fighting for division, but for uniting the population,” Azevedo tells Xtra. “A society that is safe for an LGBTQ+ person will also be safe for those who are straight and cisgender. If a trans person gets a job, it means that the entire population will also have access to employment.”

While the right-wing parties and politicians present a serious danger for LGBTQ+ populations, Cassiano also warns that cis white straight men on the left are not their saviours. They often steal the spotlight from queer racialized women, who are the backbone of the resistance to Bolsonaro. This lack of support from left-wing and progressive parties results in a movement that isn’t fully united. “What I’m noticing is that while there’s a strong, militant resistance coming from LGBTQ+ movements, as well as women who are against Bolsonaro and everything he represents, these forces are still dispersed and diffused,” Azevdo says. “They will need to restructure themselves in the next election cycle.”

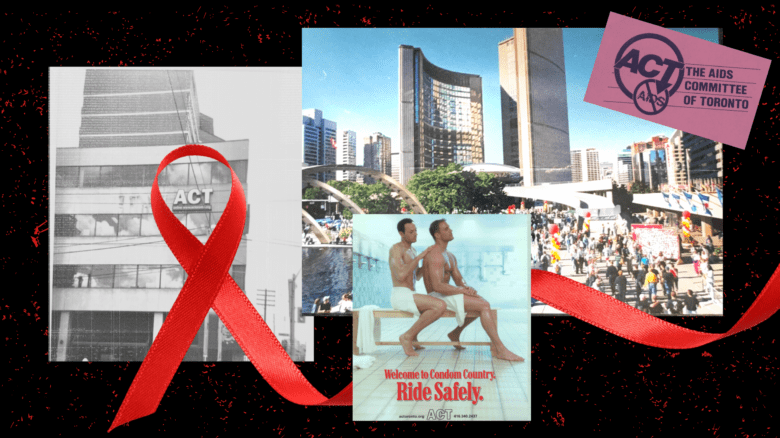

Credit: Eraldo Peres/AP Photo

Most LGBTQ+ candidates are supporters of Luiz “Lula” Inácio da Silva, the Workers’ Party candidate for president, currently ahead in national polls. The ex-president is considered the candidate most likely to beat Bolsonaro. A VoteLGBT poll taken at the São Paulo Pride parade in June revealed that 86 percent of attendees are supporting Lula’s candidacy. Lula, who was president from 2003 to 2011, and his successor, Dilma Rousseff, have a proven pro-LGBTQ+ track record. It was under the Workers’ Party that queer grassroots movements were invited to develop policies and demand more rights. That hadn’t happened before—up until that point, LGBTQ+ activists mostly operated in the margins and were not given space or weight in institutional politics.

According to Caia Maria Coelho, a trans activist from the Pernambuco Association of Travestis and Transsexuals, a local chapter of the legal nonprofit Rede Trans Brasil, the Workers’ Party government under Lula made the community more visible, particularly through the creation of campaigns like “Brasil Sem Homofobia” (“Brazil Without Homophobia”) and policies that shifted how gender identity is understood in the public health system, thus providing trans people with essential gender-affirming care.

“LGBTQ+ people in Brazil have to resist conservatism, but the ideal environment for our candidacies to thrive and our projects to grow is in a left-wing government that is adamant about leftist policies and projects,” Coelho says. “Is the growing number of LGBTQ+ candidacies in response to conservatism or despite it? We will only be able to thrive politically when the government is less violent toward our populations and when we have a government who stimulates and encourages our movement.”

“The ideal candidate does not exist. However, Lula is the candidate with the greatest possibility of defeating Bolsonaro at the polls, and this is our priority.”

The presidential election is decided through popular vote in a two-round system. If a candidate receives more than 50 percent of the vote in the first round, that candidate is declared the winner and a second-round runoff is not needed. That is what many Lula supporters are hoping will happen.

“The priority of the movements is to defeat Bolsonaro, so we have joined efforts to elect Lula in the first round of the election, because we know that in an eventual second round it will require even more resistance and strength from us to win the election,” says Marília Freire, Socialism and Liberty Party senate candidate in the state of Amazonas. However, Freire warns that Lula is not the ideal candidate. Many on the left have criticized Lula’s previous governments for making too many concessions with centre and right-wing parties. “The ideal candidate does not exist. However, Lula is the candidate with the greatest possibility of defeating Bolsonaro at the polls and this is our priority.”

For Coelho, the election of Lula and the end of Bolsonaro’s government would usher in a kind of LGBTQ+ politics that is less reactive and more focused on building permanent policies around queer and trans rights. The constant state of panic and reaction motivated by Bolsonaro’s anti-LGBTQ+ presidency, Coelho says, will subside with a return to a Workers’ Party government.

“Our movement will only grow expressively when we aren’t dealing with constant political repression by public authorities,” Coelho says.

Correction: September 29, 2022 8:14 amAn earlier version of this story had the wrong affiliation for the group Pernambuco Association of Travestis and Transsexuals.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra