One of the most politically charged issues in Canada at the current moment is undoubtedly the provision of gender-affirming healthcare to youth. Politicians, pundits and transphobic influencers are peddling the myths that such healthcare is dangerous and too easy to access. With so much misinformation circulating, it can be difficult to piece together an accurate and clear picture of what gender-affirming care for youth actually looks like in the country. What sort of healthcare is available? Do parents have any say? Is the care kids are receiving safe, and is it effective?

To set the record straight, Xtra spoke to legal and medical experts across Canada to answer these and other commonly asked questions about gender-affirming care for youth.

At what age do kids start to understand their gender?

Let’s get one thing straight right off the bat: youth can and do know their own gender identity “well before they reach the age of majority.” That’s according to Dr. Arati Mokashi, medical director of the Trans Health Endocrinology Clinic at IWK Health in Halifax, Nova Scotia. When she established the clinic in 2012, it was the first of its kind in Nova Scotia. Mokashi has spent the intervening years working with gender-diverse children and youth, their families and LGBTQ2S+ experts in the province.

The British Columbia Children’s Hospital’s (BCCH) Gender Clinic and Trans Care BC are two organizations that help to provide gender-affirming care to youth in the province, from medical interventions to mental health supports to help with the social dimensions of transitioning. Medical experts at both institutions agree with Mokashi. A spokesperson who talked to Xtra on behalf of both orgs said that “children begin to know their genders from a very young age. Some start expressing their gender as young as age three.”

However, Mokashi says, “[There is] no exact age at which a child knows their gender identity.” Research into gender identity formation has largely focused on cisgender children. Amongst gender-diverse children, “some will start to exhibit differences in gender identity and assigned gender quite early, whereas others may be well into their teen years.” It depends on the individual youth.

On average, kids are a little over nine and a half years old when they first realize their gender differs from the gender others see them as.

Are kids being offered irreversible surgeries in large numbers?

Gender-affirming healthcare is just one part of gender-affirming care.

Not everyone wants, needs or qualifies for hormones or surgeries. That’s why “gender-affirming healthcare also includes other care,” Mokashi says. Care providers help with everything from using a child’s proper name and pronouns, providing mental health supports, addressing issues such as bullying and harassment, connecting parents with supportive groups in the community and helping youth access gender-affirming garments, Mokashi explains.

In other words, while doctors and other medical providers have a role to play in providing gender-affirming care, parents, friends and gender-diverse youth themselves have a major role in ensuring well-being.

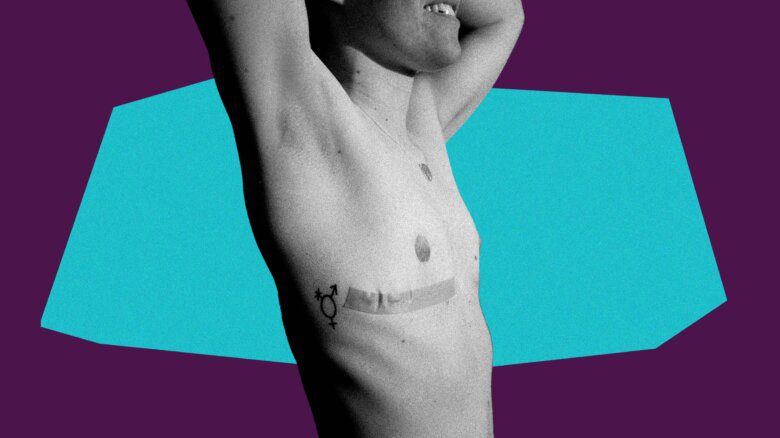

As for surgeries, some youth in Canada are eligible for top surgeries (funding and age limits vary by province), but they’re rarely performed. In Alberta, for example, only 23 people under 18 years old received top surgeries in 2023—but it is unclear whether all were conducted as gender-affirming care, or for other reasons such as cancer care or breast reductions.

Bottom surgeries aren’t available for youth in Canada at all.

In Nova Scotia, where Mokashi practises, the only gender-affirming surgery available to youth is mastectomy with chest contouring; and it is only available to youth aged 16 and 17 “by exception.” That means youth must meet all the standard criteria for accessing this surgery and also demonstrate some other exceptional circumstance—for example, severe gender dysphoria that prevents them from participating in school or other activities.

A representative from BCCH and Trans Care BC say that top surgeries are only occasionally available to people younger than 19 (the age of majority in that province). “Age, maturity, capacity, time on hormonal treatments, severity of gender dysphoria, support for aftercare and parental/caregiver support and many other factors are all considered on an individualized basis between the patient, their caregiver/family and their medical care team,” they say.

In reality, much of the gender-affirming care youth receive is not medical in nature. The representative from BCCH Gender Clinic and Trans Care BC was clear: “The main focus of treatment available for adolescents is support for the social aspects of transition. This can include support for navigating relationships such as family dynamics and safety and inclusion issues with peers, in school settings and other spaces.”

Are puberty blockers safe for kids?

Puberty blockers are also known as “hormone-suppressing agents.” They work by countering the puberty-causing effects of the hormones of the sex that person was assigned at birth.

One of the reasons puberty blockers are prescribed is to give gender-diverse youth an opportunity to explore their gender identity without the pressure of being forced through the puberty of the sex they were assigned at birth. The idea is to delay puberty so that kids can decide whether to pursue other medical interventions, like hormone therapy. Their use has been endorsed by the Canadian Paediatric Society, among other medical organizations.

The effects of hormone-suppressing agents are reversible. According to guidelines put out by the Canadian Paediatric Society, “endogenous sex-steroid production and/or effects will resume if hormone blockers are discontinued.” In other words, if they stop taking blockers, youth will go through the puberty of the sex they were assigned at birth. By contrast, puberty has many irreversible effects, such as the development of breasts in those assigned female at birth, or voice dropping in those assigned male at birth.

Puberty blockers are effective. Those who want and receive puberty blockers report lower levels of suicidality compared to those who want but do not receive them. In short, they save lives.

Do hormones cause permanent changes? ?

They might.

According to the Canadian Paediatric Society, reversible effects of testosterone include the development of acne and the suppression of menstruation. However, there are irreversible effects, too. These include voice deepening and growth of body and facial hair.

Reversible effects of estrogen include skin softening and fat redistribution. While the primary irreversible effect is the development of breast tissue.

Because there is the possibility of permanent changes, the process for accessing gender-affirming hormone therapy is quite strict. In Nova Scotia, for example, to access hormone therapy, youth must go through an in-depth assessment by a trained mental health clinician, who will meet with the child and their guardians over several sessions, Mokashi explains. That is in addition to the assessments that physicians perform to determine the suitability of hormone therapy for kids who request them.

On average, kids wait 13 to 14 months from the time they first seek hormone therapy to the time they actually receive it.

Are kids being rushed into transitioning in Canada?

Quite the opposite. Relative to general healthcare of the sort you would get from a standard family doctor, gender-affirming healthcare is difficult to access. One study, using 2019 data, found that among trans and non-binary Canadians of all ages, roughly 41 percent of those “who needed but had not completed gender-affirming care” were on a wait-list for such care. At the Alberta Children’s Hospital’s Pediatric Gender Services Clinic, for example, wait times to access care can be a year or more.

Exacerbating the long wait times to access specialized gender-affirming care is the fact that, across Canada, between 34 and 68 percent of trans and non-binary people lacked a family doctor with whom they felt comfortable discussing issues related to gender identity and expression.

In short, gender-affirming healthcare is very difficult and slow to access, for youth as well as for adults.

What safeguards are in place to keep youth from being “pushed” or “rushed” into medical transition?

Plenty.

Mokashi is clear: “No child should be pushed or rushed into life-altering decisions, particularly related to starting medications which may lead to potential permanent physical changes.” And that means each case must be evaluated individually.

Across Canada, assessment guidelines are strictly observed. Parents and guardians, as those “who know the child best,” are almost always involved at every step, Mokashi says. Doctors weigh the risks of treatment (for example, weight gain and hot flashes as side effects of puberty blockers) against the potential benefits. And “hormone therapies that may cause permanent changes aren’t started until the youth can weigh in on and demonstrate a persistent, consistent, stable gender identity and demonstrate an understanding of the risks and benefits,” Mokashi tells Xtra.

As both the BCCH Gender Clinic and Trans Care BC told Xtra, “many children and adolescents take significant time and thought to share personal information about gender diversity with those they love.” Before kids receive any gender-affirming medical care at BC Children’s, they undergo “multiple assessments and consultations from a range of specialists … to address both their physical and mental well-being.”

“The bottom line,” Mokashi says, “is that no medical therapies are ever started quickly or without careful assessments. Evidence-based medicine is always practised, as with all other areas of medicine.”

Do parents have any say in the care their children receive?

In almost every case, yes.

“The World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) guidelines stipulate that all the assessments must include a parent/guardian (as long as it is safe to do so),” Mokashi says.

That means the only circumstances in which a youth’s parents are not involved in their care are, realistically, ones in which there is a genuine risk of abuse and family violence.

Can withholding gender-affirming care harm youth?

Yes.

The available research indicates that conversion therapy is actively harmful to the youth who experience it: it causes psychological distress, depression, substance abuse and suicidality.

Florence Ashley is an assistant professor at the University of Alberta, Faculty of Law, and an expert in the legalities and ethics of conversion therapy.

According to Ashley, forcing youth to go through the puberty of the sex they were assigned at birth constitutes a form of conversion therapy “as it effectively changes their body away from their desired gender expression and, in many ways, discourages and represses it.” Ashley also points out that these attempts to repress trans youth’s gender identities and expressions are at the core of attempts to ban gender-affirming care: “legislators hope that endogenous puberty will make trans youth ‘grow out’ of being trans, or are simply hostile to the very idea of youth being trans.”

Is gender-affirming healthcare safe for kids?

Yes.

In its statement concerning gender-affirming healthcare for youth, the Canadian Paediatric Society found that gender-affirming hormone therapy “is considered safe for adolescents,” although there are some minor risks as with any medication regimen (such as, for injectable hormone therapies, tenderness at the injection site).

Trans Care BC and the BCCH Gender Clinic note that patients and their families are informed of both the risks and the benefits of potential medical interventions before any medications are prescribed, and that, in Canada, the gender-affirming therapies currently in use “have been available for over 30 years, and significant evidence exists on their safe use.” Clinicians at the Gender Clinic also perform regular follow-ups with patients to monitor for medication side effects.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra