Probably after your lover(s) and your mother when you were a child, the person who is most intimate with your body is your doctor.

He or she probes all the orifices of your body, asking personal questions about its functions, taking notes of your responses. Yet how comfortable are we, individually or as a community, with being open about our sexuality with doctors? How free do we feel to explain the symptoms we think we may have, particularly those of a sexual nature?

Talking about the issues that matter to us, that define who we are, exposes our innermost desires, thoughts and fears; the very things that religion and society, despite years of change, still tell us to disguise, not to discuss?

So many of us have personally experienced discrimination. Can we ever predict whether honesty with a doctor will be met with brusque dismissiveness?

It was only 30 years ago that homosexuality stopped being classified as an illness requiring psychiatric intervention. It is true today that there are gay images and gay issues everywhere you turn, and we understand them. But for many straight people, unless it hits them between the eyes, they simply don’t pick up on the clues we relentlessly drop. They don’t understand our underlying concerns.

In a 1997 study by the Coalition for Lesbian and Gay Rights in Ontario, an astounding 87 percent of Ontario gays, lesbians, bisexuals and transsexuals who were polled indicated they had suffered discrimination from the medical profession.

Furthermore, 70 percent of the respondents had actually been insulted about their sexual orientation by health-care providers. These are shocking statistics when you consider that for young gay people the suicide rate is two to three times higher than it is for straight youth.

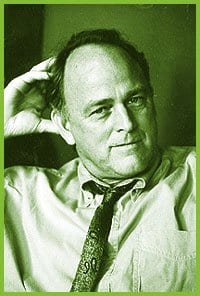

For the past 10 years, Dr Bob Birnbaum, an Ottawa family practitioner, has been making presentations, accompanied by members of Ottawa’s gay and lesbian community, to second-year medical students at the University of Ottawa. The impetus for this came from both students and faculty at the university. They were responding to concerns they had heard about homophobic comments and attitudes reported in the medical school and city hospitals.

Last November, Dr Birnbaum, accompanied by a lesbian medical student, a gay couple, an out representative of the Youth Services Bureau, a transsexual and a gay youth, presented firsthand how each panelist had been treated by medical personnel. They were also enlightened as to how gays, lesbians, bisexuals and transsexuals want to be treated by their doctors. A key part of the presentation was the individual coming-out experiences. This set the discussion firmly on the context – what it is to be gay, lesbian, bisexual and transsexual in Canada today.

The medical students had an opportunity to become familiar with GLBT slang – top, bottom, friend of Dorothy, gaydar, sings in the choir, etc. They explored the persistent myths – “it’s a phase,” “it’s a choice,” “nature versus nurture,” “gays are effeminate, sex-obsessed and child molesters,” “lesbians are masculine,” “they just want to be the other sex.”

The students learned how easy it is to be perceived as heterosexist when using terminology, such as family values, which may have a certain connotation for them, but a very different one for GLBTs.

It was underlined that the composition of the family structure has changed irrevocably. Today, as was illustrated by the gay couple Jay Lawrence and Jean-Marie Belanger, gay and lesbian couples lead happy, fulfilled lives and have, for the most part, been accepted by their neighbours and take active roles within their larger community.

The couple discussed how they interact with their parents and their brothers and sisters, how they go about their daily lives.

Sue Pihlainen, who works for the Youth Services Bureau, told of her struggle to find a medical doctor who would artificially inseminate her when she and her partner decided to raise a family. The first doctors turned them down because they were lesbians. But persistence on their part paid off when they found a doctor who agreed. Today, Sue and her partner have two children, eight and 10 years of age.

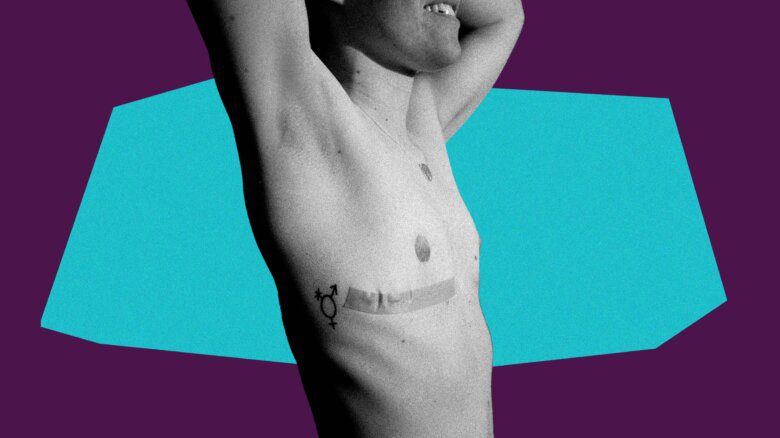

The class heard from Jordan Kent, a transsexual who had spoken to a class the year before while still a woman. She recounted her experiences since deciding to live as someone of the opposite sex. When she confided to a female doctor that she was not interested in having sex with a man, the doctor couldn’t comprehend this, remaining insensitive to the true wishes and feelings of Jordan.

Such negativity only compounds the difficulty young gay people face in accepting who they are, the students were told.

All too often, youth carry negative self-images that society puts forward – sometimes subtly, other times bluntly – about homosexuals. This negativity can require a lifetime of effort to dispel.

Nathan Hauch told of being a gay disabled youth and of his wish to assist other GLBT youth to build positive images of themselves. He underlined for the students that, as a son of a minister, his faith inspires him.

A member of the panel was Christy Haywood-Farmer, a second-year medical student. On her first day as a medical student, she stood up and proclaimed her sexual orientation. Having just arrived in Ottawa from western Canada, she decided that she would no longer hide her true self. She thanked the students for being so welcoming and accepting of who she is.

Hopefully, these future doctors will remain open and attentive to gay patients in the decades to come. Hopefully, they represent a new trend in the medical profession across Canada, one that will see that 70 percent figure dramatically drop.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra