My first memory of addiction is watching my birth mother drown a bottle of sleeping pills with a bottle of vodka. I was eight, and I didn’t know if she would wake up. I brought her water, played her favourite movies on the VHS, and counted the hours she’d been out.

By the grace of the universe, I never developed a substance use disorder. I went through college and grad school and my 20s without any of the drinking and partying common in early adulthood. I went to bed at 10, woke up at seven and limited my consumption to a half glass of wine with dinner a few times per year.

After I moved to the Bay Area and got involved in sex-positive queer communities, I got used to saying no, over and over: No thanks, I don’t use weed. No thanks, I don’t want to go to that party featuring ecstasy and GHB. No thanks, I can’t have sex with anyone intoxicated. It took time and effort to find queer, sex-positive, sober spaces.

I know I have a genetic predisposition to addiction. Over the years, I’ve watched people I care about struggle with this illness. And it is an illness, just as physically rooted as diabetes or knee pain.

Credit: Courtesy of Tauheed Zaman

Tauheed Zaman, MD, is an associate clinical professor of psychiatry at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) School of Medicine and the associate director of UCSF’s addiction psychiatry fellowship program. He’s triple-board certified in psychiatry, addiction psychiatry and addiction medicine. He’s also an out gay man, a Bangladeshi immigrant, a singer and a trained sex educator. During medical school, he doled out lube, condoms and advice about sex and drugs in Boston nightclubs as the Sparkle Ranger, complete with a rhinestone cowboy hat. When it comes to queer communities’ challenges with addiction, he’s seen it all.

As concern about substance use disorders and isolation is on the rise during the pandemic, people still need to connect. Xtra reached out to Zaman to ask how queer folks can navigate addiction during the pandemic with a compassionate, harm reduction mindset, especially if they’re stuck at home with less than understanding family members.

Let’s define some basic terms. What is addiction?

Addiction is a relapsing and remitting disease, much like diabetes. It’s a brain disease—not a matter of character or poor choices. It’s a real medical condition that warrants evidence-based, nonjudgmental treatment.

The colloquial definition is the ongoing use of a substance despite consequences. The medical definition is a series of substance use disorders: Alcohol use disorder, cannabis use disorder, stimulant use disorder and so on. These days, we use 11 criteria to say someone has a substance use disorder, and whether it’s mild, moderate or severe. The criteria have to do with impact on functioning, loss of control and physiologic dependence.

Almost any substance that can be harmfully used and hard to give up can go into the blank space of _____ use disorder.

How do these kinds of disorders develop, and are they different based on the substance or the behaviour?

Certain aspects of someone’s history make it more or less likely that they’re going to develop a disorder if they’re exposed to a substance. People with a strong family history or a genetic predisposition to any substance use are much more likely to develop any kind of substance use disorder. People who have histories of trauma, depression, anxiety and other psychiatric comorbidities are also more likely to develop substance use disorders.

I also want to call out the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACES) trial, which lays out many of the childhood risk factors for future mental health concerns, including substance use. Risk factors include experiencing and witnessing violence, including suicide attempts. Nadine Burke Harris, California’s amazing surgeon general, gave a great TED Talk on it.

So if you imagine two people—one of whom has a bunch of these risk factors and one of whom doesn’t—and you put them in the same situation, how might that play out?

That’s been studied scientifically with a concept called delayed discounting. The basic premise is that if you offer someone $5 now versus $10 in an hour, people who have an addiction history or predisposition will opt for the reward now, because that’s what their brain is primed to do: Seek immediate gratification. People without that history or predisposition will take the $10 in an hour. It’s an oversimplified example, but it illustrates the concept.

Two people who otherwise might look the same, and even have similar physical health profiles, can have very different neurologic profiles and responses to rewards.

What protective factors help prevent or manage addiction?

The things that help are the things that you would expect: Really good social support, really good insurance, housing, not having other significant medical or cognitive issues. All of those are significantly tied to better outcomes.

That means for our patients who come in the door without those protective factors, we have to provide them targeted support to succeed. We have to help them with housing, social isolation and insurance issues. We all spend so much time fighting with insurance companies because we’re helping build up those protective factors that will help people succeed in addiction treatment.

If somebody is looking to see a provider about an addiction, who should they go see first?

If someone has a concern about substance use, I actually think primary care is often the best place to start. That’s to make it easier to identify any medical issues that need to be addressed right now to prevent harm, and to order any lab work.

Primary care doctors also have access to basic screening tools to give them a sense of, “Is this an alcohol use disorder, a cannabis use disorder, a stimulant use disorder? What’s going on?” And then they can refer you to the appropriate provider.

People in the U.S. can also search for providers on findtreatment.gov. In Canada, a good place to start is this guide from the Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction.

For specialist referrals, what’s the difference between addiction psychiatry and addiction medicine?

Addiction psychiatry promotes the evidence-based diagnosis and treatment of substance use disorders. Treatments that work include pharmaceuticals and behavioural interventions. Addiction psychiatry also encompasses the treatment of anxiety, depression, trauma and any other mental health issues someone comes in with, since usually substance use disorders don’t show up alone.

Addiction medicine is also focused on substance use disorders, but a bit more on the medical and physical consequences—like liver disease, heart disease and kidney disease—and a little less on the psychiatric issues like depression, anxiety and PTSD.

Addiction psychiatrists have a real emphasis on evidence-based diagnosis and treatment in the context of co-occurring psychiatric conditions. Addiction medicine doctors can treat an addiction and prescribe you your PrEP, get you into hepatitis C treatment and help you get your cholesterol down.

The two fields really fit together, and for me, it’s really cool to be on the faculty for both of these training programs at UCSF.

Let’s talk about abstinence versus harm reduction approaches.

Abstinence used to be the gold standard treatment for addiction. The idea was: Do whatever you can to brow beat your patients into being abstinent from a particular substance or behaviour.

That doesn’t work for a lot of people. It turns out we have to have a harm reduction approach for many people to succeed. Some people go from harm reduction to abstinence; some people don’t.

Part of treating the whole person is understanding their goals for treatment, and supporting them in abstinence if that’s what’s appropriate and harm reduction if that’s what’s appropriate.

Given that approach, what are some of the ways treatment might look?

Treatment is broadly broken down into pharmacotherapy and behavioural treatment.

A lot of people don’t know there are actually FDA-approved medications for specific addictions, and there are a whole bunch of medications we can use off-label. For example, there are three FDA-approved medications just for alcohol use disorder that have been around for decades. Doctors rarely think to talk about them, even though they’re cheap and generic and widely available, and patients often don’t think to ask. Similarly, there are FDA-approved medications for smoking cessation and opioid use disorder. And there are good, evidence-based off-label medications for meth use disorder and cannabis use disorder.

Choosing a medication requires careful consideration of risks and benefits, and I’d encourage everyone to discuss the options fully with a physician before choosing a medication for any substance use disorder. Medications to discuss include:

- Alcohol use disorder: naltrexone (oral and injectable), disulfiram and acamprosate are FDA-approved to treat alcohol use disorder in the U.S.; in addition, topiramate and gabapentin are used off-label

- Opioid use disorder: buprenorphine, methadone and naltrexone (injectable) are FDA-approved to treat opioid use disorder in the U.S.

- Tobacco (nicotine) use disorder: nicotine replacement, bupropion and varenicline are FDA-approved to treat tobacco use disorder in the U.S.

- Stimulant (meth) use disorder: mirtazapine is used off-label; a combination of bupropion and naltrexone is also used off-label

- Cannabis use disorder: n-acetylcysteine and gabapentin are used off-label.

That said, medications aren’t the be-all and end-all, or appropriate for everyone. Behavioural treatment is the mainstay.

12-step gets talked about a lot, and it does have a good evidence base that works for a lot of people. It’s where you’re working through all the steps of recovery in Alcoholics Anonymous, Narcotics Anonymous, Crystal Meth Anonymous, etc. But there are so many different flavours of that, so I like to tell people to look around. Some 12-step meetings do away with God and spirituality altogether and are very secular. Some are focused on mindfulness or dharma or zen. Some are for women, for men, for other genders. There’s a punk rock 12-step meeting. There are so many options.

Beyond 12-step, the best evidence is for cognitive behavioural therapy and group motivational interviewing, both of which really, really help. Motivational interviewing takes a nonjudgmental stance and hones in on the person’s own values and their intrinsic desire to change. It’s a much more person-centred approach to medical care.

Finally, contingency management is huge and I wish more people had access to it. Contingency management is the gold standard treatment for stimulant use disorder—meth and cocaine. If you try contingency management, you’ll come into a clinic twice a week to test your urine. For every negative test, you get to reach into a fishbowl and it’s a lottery; you have a chance of drawing a reward. It turns out that is the most effective intervention for stimulant use disorder.

So my overall message for people is, let’s talk about both of these big options—medications plus or minus behavioural treatment—but understand that there are so many flavours of each that we can use to target what works for you.

How can you tell if a physician has their shit together in terms of how they treat addiction? As in: If they’re really evidence-based, up-to-date on the science and not going to be shaming?

Ask them if they have any specialty training in treating substance use disorders. Ask them about their experience prescribing specifically for those conditions. If a physician is diagnosing you with a use disorder, they should be able to tell you what the evidence-based treatments are for that diagnosis, or refer you to a trusted colleague who can. Their discussion of treatment options should include medication and behavioural treatments.

If a doctor says you have a use disorder and you’ve just got to stop because your heart can’t take it anymore and that’s it, that’s the extent of the conversation, that is probably not someone who is addiction trained or informed. That’s a bunch of scare tactics. And it turns out that, in addition to not being nice, that approach does not work.

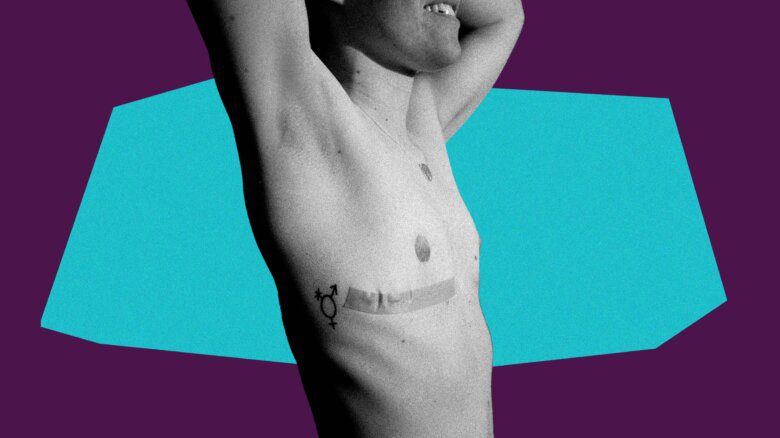

What do queer and trans people need to know about addiction in their communities?

I’m really grateful to work with patients who identify with any part of the queer community, because, as Johann Hari said, the opposite of addiction is not sobriety—it’s connection. Connection and supportive communities can be a huge strength in terms of recovery.

Queer people report higher rates of cannabis, opioids, alcohol and tobacco use compared to their heterosexual counterparts. And substance use disorders also tend to occur at higher severities for queer people, which could just mean they’re not showing up to care until later.

“The opposite of addiction is not sobriety—it’s connection.”

That might be due to the minority stress model, which says that the more minority categories someone fits into, the more vulnerable they are to certain types of illnesses over the long term because of the cumulative impact of homophobia, transphobia, racism, all of those things.

All that said, the standard treatments that help others can be effective for queer people as well, including pharmacotherapy and behavioural treatments. The research clearly shows that queer-focused treatments work better for queer people, but less than 10 percent of programs in the country actually offer queer-specific, culturally competent addiction treatment.

So I take all of that into account in talking to my queer patients. The overall messages are: Your queerness can be a strength rather than a liability; yes, these problems occur at higher rates, but there are good reasons for that; and association is not causation. There’s nothing wrong with you. It’s not your queerness that’s leading to your addiction. Let’s help you get connected to treatments that work, and also have some level of queer competency, which is so important and also hard to find.

How do you evaluate a provider for queer competency?

I’m a queer-identified provider. I’ve sought out queer-identified providers for myself and for patients. Ask a provider to tell you about their experience treating folks like you.

Look for a provider who introduces themselves, states their pronouns, doesn’t make assumptions about your orientation or gender and asks about your identity in an empathetic, matter of fact way as a part of their care and getting to know you. Those are all good signs that someone has some awareness and sensitivity towards treating queer people.

It’s also good to look for a provider that is trauma-informed. It’s not uncommon for queer people with addictions to have a trauma history. Look for a provider who takes a good history, but doesn’t push too far. For example: Someone who says, “Hey, we’re going to talk about some stuff that can be hard. Let me know if it’s uncomfortable for you.”

Do you see parallels between abstinence-only versus harm reduction approaches in sex ed and addiction treatment?

I see a lot of people who use substances in the context of risky sexual behaviour. A lot of patients choose abstinence, and say, “Oh my God, I use meth with other guys during hookups, sex with multiple guys at once, more anonymous sex, unprotected sex a lot of the time. You have to help me stay away from sex and meth because the two are so tied together.” And so we’ll define relapse and relapse prevention for the substance and for sex. And it is not unusual for patients to set goals of abstinence around both saying, “You know what? I need to not have sex with another person for six months because I’m trying to stay away from meth.”

And I’ll say, “Okay, I’ll support you. How could you reach that goal? Who can help hold you accountable? What apps will you delete from your phone?”

Some patients choose harm reduction, and say, “I’m only going to have sex with one other person who I know and trust to be sober,” or “I’m only going to have sex with myself.” I’ve had so many patients hand me their cellphone and be like, “Hey, can you just delete Grindr for me? Just do it.”

So I think harm reduction can be applied just as easily to risky sexual practices as it can to substance use.

What particular drugs are most often used during sex? What do they do?

The most common drugs in people’s systems when they have sex are actually the most commonly used substances overall: Alcohol, nicotine and cannabis. Three other classes of drugs have gained notoriety in the LGBTQ2S+ community for their association with sex, though plenty of straight people use them too:

- Hallucinogens/club drugs like MDMA (ecstasy/molly), gamma hydroxybutyrate (GHB/G) and ketamine (special K). Many of the queer patients I’ve worked with encounter these drugs at raves or circuit parties, or even during casual sex. Hallucinogens can create euphoric or disinhibited states which can enhance sex, but can also cause dehydration, respiratory depression, injuries sustained while high and, in the case of GHB, medically risky withdrawal including the risk of seizures. Rohypnol, the date rape drug, is also sometimes placed in this category, and causes an extremely relaxed state along with amnesia, which leaves a person vulnerable to sexual assault.

- Stimulants like cocaine and methamphetamines. These uppers can provide a boost of energy and create a euphoric high followed by a crash. The high can facilitate sex, but all stimulants carry significant health risks, including addiction, cardiac arrhythmias, strokes and death. For those who use these drugs via injection, sharing needles or works [other drug injection equipment] increases the risk of skin infections, heart infections, hepatitis C and HIV.

- Inhalants like amyl nitrate (poppers). Inhalants relax blood vessels and smooth muscle, which makes it easier to bottom vaginally and anally. They can cause headaches and lightheadedness. They are short-acting, which means people often end up taking multiple hits during sex. I always advise LGBTQ2S+ patients who plan to use poppers to proceed with caution, and be careful about injuries that they could sustain to their vaginal and anal tissues, particularly if they’re attempting fisting or inserting larger objects. Having a caring and experienced partner can be a great form of harm reduction.

Any other advice around sex and drugs?

Sober sex—and amazing sober sex—is really possible! It can take a while to get there for someone who might be used to having sex exclusively while using drugs. But with the right support, behavioural and/or medical treatments, people can get there—I’ve seen it happen countless times.

“Sober sex—and amazing sober sex—is really possible!”

We’re a year into the pandemic, and public health authorities have been asking people to stay away from other households this whole time. You talked about how the opposite of addiction is community. How has COVID-19 affected substance use rates?

We’re still gathering data, but I can tell you about my sub-specialties, opioids and cannabis. What we know so far is that opioid overdoses are up, and patients are using much higher doses of cannabis more frequently. Perhaps most concerningly, people who have other mental illnesses—who are more depressed or anxious or psychotic, for example—are using cannabis at much higher rates than people who do not have those conditions.

Social isolation is hard on anyone. For people in recovery, if they’ve suddenly lost access to their home AA group or meeting or can’t meet up with their sponsor who is a real pillar of their recovery, it is a huge blow to their treatment and mental well-being.

In that context, it makes sense that there are more relapses and more people using alone. It’s particularly risky to use opioids when there’s no one around to give you Narcan or CPR or to call 911 if you overdose. As a result, there’s now a hotline called Never Use Alone where someone will stay on the phone with you while you use, and call for help if needed. I’ve been talking to patients about these scenarios and helping them to plan ahead.

All that said, there have also been some significant silver linings. Some people don’t have access to their usual dealer, and they feel great without substances in their systems. Some people don’t want to have to mask up and risk getting COVID-19, so they’re not using, and they’re feeling better. And I’m like, great, we’ll take it. We know that addiction rates go up when there’s more access to a substance, and rates go down when there’s less access to a substance. For some substances, the pandemic has reduced access.

How has the pandemic shifted access to addiction treatment? What’s better, and what’s worse?

Many of my patients don’t have a phone, much less a laptop or an iPad or a reliable wifi connection. That makes it hard to access newly expanded telehealth services.

That said, for my patients who do have a phone or a way to join a video call, I can call them and prescribe medications, including controlled substances. It means patients no longer have to drive 100 kilometres, find parking and become aggravated in the waiting room because I’m running behind. That’s because of reduced restrictions placed on physicians and increased infrastructure at hospitals. Suddenly, I’m seeing people who are 400 kilometres from San Francisco, all the way up in Eureka, California. They’ve now been sober for the entire pandemic because they suddenly have access to care. I really hope these gains last beyond the pandemic.

I want to talk more about the loss of in-person community. We’re starting to say “physical distancing” over “social distancing” because of the acknowledgment that social support is important for everyone. That’s especially true when the opposite of addiction is community. So for folks who just really miss the physical presence of their local AA or other group, who may also be touch starved in other ways—what do you tell them?

First of all, it has to start with a great deal of empathy.

There are physicians, particularly those of us who’ve seen patients die of COVID-19, who might take the approach of saying, “You know what? Yeah, that sucks, but it doesn’t suck as much as dying of COVID, so deal with it.” And that’s an understandable approach, but not a helpful one.

It’s more helpful to acknowledge how tough it is and think about ways to problem solve with a harm reduction approach. For example, I’ll ask, “What’s reasonable for you? What is the reasonable or acceptable amount of risk you’d be willing to take in order to get that need met?”

Does that mean you have to be proactive and reach out to some trusted people to form a sobriety pod? What period of time is enough for that? A weekend? A week? Longer? How do you talk to people about getting tested and sharing their results with you before you pod up?

It could also be companionship, cooking together, sex, support groups, whatever connection might be crucial for you.

Talking to people about acceptable risks for themselves, helping them balance the importance of their mental health, including their kind of addiction support, with some of the very real infectious disease risks of COVID-19, are in a way the kind of harm reduction we’ve been doing all along. But now we’re applying harm reduction to both substance use and COVID-19 risk.

Maybe someone is trying to get sober, but they’re living with a partner or roommate or friend who drinks socially, or who also has a disorder and no interest in treatment. If someone is stuck in a non-sober household during the pandemic, what can they do?

Boundary setting is so incredibly important in any relationship, but particularly important in recovery—especially that first year of early recovery. So I like to help people think about it that way, that you’re in this acute phase where protecting yourself and trying to keep your environment safe during this acute phase is the most important thing. And there are different ways to have that conversation: You have a right to your space and to ask for what you need in order to address your medical health. I encourage people to talk about it in that way, to talk about their needs as a real medical necessity.

I encourage them to sometimes even use my name or to use my profession and say, “My doctor told me that I cannot be around marijuana smoke,” or, “I cannot have a single drink of alcohol, and you leaving a bunch of beer bottles on the table everyday is making that really hard.”

It’s about empowering people to set boundaries to the degree they safely can, helping frame it as a medical necessity during that early recovery period, and assuming that the person agrees, offering education or to do joint visits with the other party. I’d say, “Hey, would it be helpful for them to hop on a call with both of us?” Now that we’re using telehealth, it’s an easy way for them to get why it’s important not to be smoking around you or using around you.

And then people ask similar questions, “What if I used to drink with that person or use with that person, and suddenly I’m like, ‘Nope, I can’t do any of that.’ How do I explain that?”

First, you actually don’t have to explain that at all. You could just do it and they should respect that. But if you need a reason, you can say, “My doctor told me to take a break.” You can say you’re on a medication that interacts with a substance (since a lot of substances interact with many medications, it’s a pretty safe bet). Or just say you’re taking a break and it’s temporary. Do what you need to do to smooth the communication over. And if you need to cut someone off because they’re too much of a risk to your recovery, that’s okay, too.

I wish everyone could just have their own solo apartment where they didn’t have to negotiate those things. But what has really struck me is that developing those skills translates into better relationships far beyond the living environment. They translate into setting boundaries and expectations with everyone in your life, including people outside the home. And that can be really important for recovery.

Any last thoughts you’d like to share?

We as queer people have a particular history when it comes to the HIV epidemic, and I think it can be really important to have conversations about sexual health and HIV risk and testing as a part of addiction treatment. I’m trying to get funding for a pilot project where we offer PrEP to all of our patients who are engaging in risky sexual behaviour around their addictions. We don’t do that yet. I’m not even allowed to prescribe PrEP, because our health care system only allows infectious disease doctors to do that.

So I’m hoping that through this lens of HIV history that we have as queer people, queer physicians like me can help expand the boundaries of treatment to treat the whole person. I want to be able to offer PrEP to everyone—to people of any orientation or any gender identity.

All of this is to say that I think there are real strengths and lessons to be learned from the queer experience and real resilience in our histories that can give us hope in treating addiction and mental health more broadly.

Comments included here represent Dr. Zaman’s professional opinion, and do not reflect that of the U.S. government or any of his employers. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra