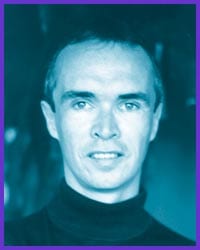

My brother, theatre artist Ken McDougall, and I grew up in a dysfunctional household. Chaos and confusion were substitutes for parents as our daily companions, and as I think back to our childhood, I wonder how we survived.

As a girl of 12, I was embarrassed because even though you were a boy, you had obvious girly mannerisms, which I had happily discarded years earlier in favour of the guy stuff that eluded you.

While I played with guns, threw footballs and climbed trees, you lovingly cared for the dolls of our younger sister, changing their clothing and hair at every opportunity. You were doing make-overs long before the world discovered Oprah.

We had so little in common, aside from our shared biology, and I mourned the lack of a real brother who could catch baseballs and run as fast as I did.

It wasn’t long before the neighbourhood kids discovered your prissy pursuits and I found myself protecting you against the damaging taunts of childhood cruelty. I developed a reputation as a street fighter, and with a few well placed punches the message was clear: It was okay for me to call you names, but woe to the outsider who dared.

I was known as the tomboy and you were the sissy. Our parents probably hoped we’d grow out of these phases and become normal respectable children, but thankfully, we didn’t.

Our closeness began with our mutual coming out declarations; adulthood held separate yet similar adventures for us. We were both drawn to the arts. I chose music, and in true baby dyke fashion became a professional drummer, travelling the countryside with a succession of mostly unremarkable girl groups popular in the late-1960s and early ’70s.

You began a brilliant career in the world of Toronto theatre, with your immense talents as an actor, dancer and director. There are half a dozen Doras engraved with the name of Ken McDougall.

I remember the times we used to meet in the bars watching the action on the dance floor, and we would have such fun critiquing the moves of the pretty boys. You filled me in on all the hidden meanings of pocket hankies, earring placements, and the latest in leather accoutrements. It was all so fascinating, and it made my no-frills lesbian life seem boring by comparison.

We made each other giggle as we switched our queer roles for amusements’ sake. I could fag it up at the drop of a pillbox hat, especially after you showed me how to flip my wrists like the models on The Price Is Right.

I would double over with laughter as you mimed the fabulous Gabriella Sabatini dyke walk, the only time you were even remotely butch, and my tears flowed as you re-created the Martina Navratilova curtsy to the royal box at Wimbledon.

You taught me a whole new language when you explained glory holes, size queens and tops and bottoms. I truly believed that bears lived only in forests.

As we got older, we ventured into the more combative state of lesbian and gay politics, debating the thorny issues that divided us then, and still cause friction today. I questioned the gay male preference for washroom encounters, public sex and orgies in the baths. You countered with the contentious themes of overweight lesbians, how dykes couldn’t be sexual without getting married and why in the name of Calvin Klein couldn’t we pay more attention to our appearance?

I worried about your lithe, dancer’s body being bruised and beaten by some ill-chosen one-night stand, and you’d stop me, midangst, with a look that said it would never happen, changing the subject by reminding me of the importance of having good hair.

We argued these points late into many nights, our voices sometimes rising to near shouting levels, while never being able to completely understand the reasons and concerns of the other. But we learned from each encounter, and always ended the night with a kiss and a warm embrace.

Our love of movie musicals provided solace to our combative spirits, especially Singin’ In The Rain and anything featuring Cyd Charisse. I always knew the latest gossip about Buddies In Bad Times, the theatre group you and Sky Gilbert created in 1979.

I’m so very glad that I have these memories of our journey together as gay siblings, and I find myself wondering about the other half of the world. I know that straight brothers and sisters have their own ways of being close, but can you imagine The Brady Bunch’s Greg and Marcia waxing rhetoric on the pros and cons of a cock ring? I think not.

It was at Casey House in March of 1994 that we expressed our love for the last time. We said our good-byes, and as I held your hand, you slipped quietly and peacefully away and I began to know the pain of missing you.

For a long time, I could not be comfortable in the company of gay men, fearing I would burst into tears at the memory of a brother who shared so much with every one of them. I’m much better now, and rather than feeling bitterness over your death, I find that I’m able to rejoice in having known a wonderful, funny, talented gay brother who complemented a lesbian sister in ways unknown to the outside world.

We were unique and special. We still are.

And to this very day… I miss you, Kenny.

The Ken McDougall Director’s Fund Award is presented during the Harold Awards, an evening celebrating alternative theatre which begins at 8:30pm on Mon, May 15 at the Rex (194 Queen St W); admission is $7. Sonja Mills hosts, with a performance by John Alcorn; playwright Sean Reycraft DJs at the afterparty.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra