I can’t help but love Provo, Utah. It’s where I discovered the magical concoction known as “fry sauce”— a pink, goopy condiment that’s really just a mixture of mayonnaise and ketchup. It’s where I first felt the thrill of driving up canyon roads and over mountain passes, pushing my hand-me-down car to its limits. It’s also where I felt the most hopeless, the most afraid and the most certain I had no future.

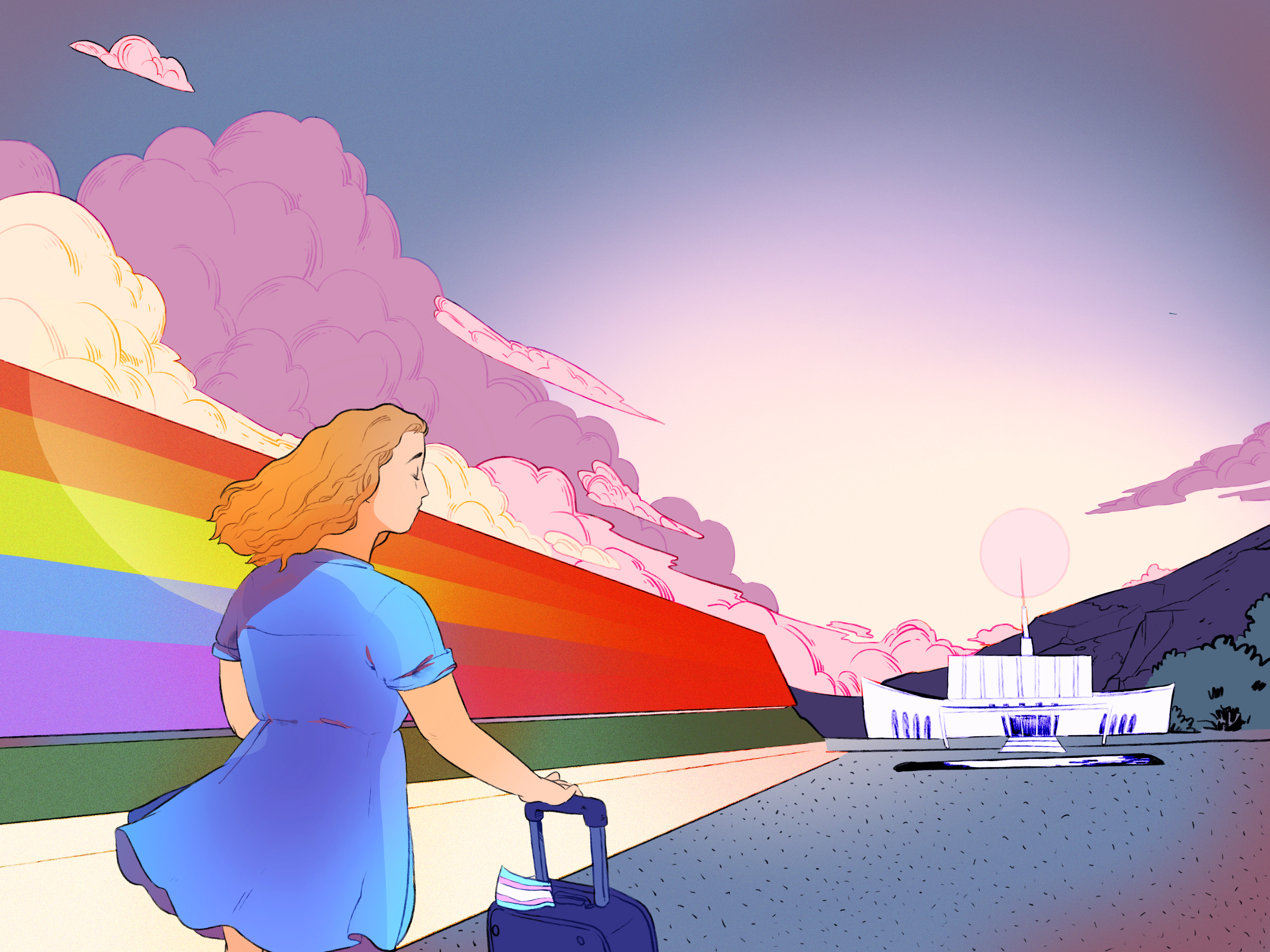

Today, I am an openly transgender woman, but I was deep in the closet in 2005 when I started attending school in that Mormon college town. As a teenager growing up in New Jersey, I turned to the religion of my birth as a way to suppress my still-nascent gender identity. Choosing to attend church-owned Brigham Young University (BYU) after high school was — in large part — an attempt to convince myself that I could become the very model of a Mormon man.

Instead, Provo became the site of my own quarter-life crisis. Not only did I stop believing in Mormonism during my sophomore year, I stopped believing that I was a boy. Sequestered in my private dorm room late at night, wearing women’s clothes and googling accounts of Mormon history, I began the slow process of coming to terms with myself.

The idea of exploring my transgender identity in any sort of public way terrified me. Not only could I potentially be expelled from BYU for violating the school’s anti-LGBTQ2 honour code, I was also living in a city where at least three out of four people were Mormon.

When I ventured outside of my dorm while presenting female, I was petrified of being seen, and I almost never left my car. College is supposed to be an auspicious moment in life, when the horizon stretches out in front of you; instead, all I saw was a dead-end. I couldn’t be myself in Provo, no matter how much I liked parts of the place.

“Provo became the site of my own quarter-life crisis.”

So I left in 2007 — back to New Jersey, back to my parents’ house, back to the town that all my peers had fled. I resigned from the Mormon Church the following year. I started over at a local community college, transferred to Rutgers University and came out as transgender in 2012.

Provo became nothing but a memory.

In the summer of 2017, when I set out to write my reported travel memoir, Real Queer America: LGBT Stories from Red States, I knew I had to go back to Provo.

The logic was simple: I wanted to tackle the most difficult part of the journey first — the remaining five weeks of cross-country travel, from Texas to Indiana to Georgia, would be a reward for surviving it.

The last time I had spent more than a few hours in Provo was a decade before. When I left the city in my rearview mirror, I cast off much of my old self, too.

“When I left the city in my rearview mirror, I cast off much of my old self, too.”

After I came out as transgender, I met the woman who would become my wife in 2013, underwent sex reassignment surgery in 2014, and got married in 2016. The scared, confused, closeted person I was in Provo didn’t exist anymore — or, at least, not entirely.

Going back there to write my book felt risky, like venturing into a house haunted by my own ghost.

On a sunny day in July 2017, I drove into Provo in a rented vehicle, my heart caught in my throat.

Memories came rushing back, fueled by familiar sensations. The sight of the Wasatch Range in the distance recalled lonely, late-night drives through the canyons up past Bridal Veil Falls. The smell of my favourite charbroiled burger place brought back every solitary dinner in my dorm room. The arid air on my skin reminded me of the last happy summer I spent here before everything came crashing down — a summer spent lazing in parks with my Mormon girlfriend, which now seems cut out of another lifetime. But above all, I felt the same, trembling terror that once pervaded my body in Provo. I fell asleep in my motel room that night worrying that the whole trip was a mistake.

The morning after my anxious arrival, I hiked to Battle Creek Falls with Emmett Claren, a young transgender man from a Mormon background who served a proselytizing mission in Utah before his transition and fell in love with the state’s natural treasures. He decided to come to school here — and to come out as transgender here — posting videos about his life in Provo online, which is how I found him. Emmett told me that the mountains around us had saved his life — that being around nature helped him come to peace with his own seemingly conflicting identities. Through Emmett’s eyes, Provo looked beautiful.

“I fell asleep in my motel room that night worrying that the whole trip was a mistake.”

Over the course of the next week, with Emmett’s help, I discovered a queerer side of Provo that has become more prominent since I left. I played card games with queer teenagers down the street from the Mormon Temple, in an old Victorian home that, in 2017, had been remodelled into the LGBTQ2 youth and family centre Encircle. It was surreal to see such joy among people so young in a place where I had once felt so afraid. By week’s end I was letting loose too, watching a drag show in a local dive bar that delighted me more than any big-city performance ever has.

The LGBTQ2 locals in Provo somehow erased my years of trauma with mere days of joy. They showed me that I didn’t have to be afraid here, as long as I was with my people.

Then it happened: I fell in love with Provo all over again.

When I lived in Provo, I liked waking up every morning to see the imposing triangle of Mount Timpanogos staring down at me from the north. I liked the “Cookies and Cream” milk from the BYU Creamery — mostly because in the Sesame Street song “Breakfast Time,” Cookie Monster sings about drinking “a glass of cookie juice” and I always wanted to know how that tasted. I liked the dated bowling alley in the basement of the student centre and the smell of dirt in the sun on the Rock Canyon Trail.

Together, all those little things added up to a single, inexplicable, gut-level attachment to Provo, one that now transcends the suffering I once experienced within the city limits. Those pleasures didn’t go away just because I did — they were waiting for me, alongside new LGBTQ2 friends, when I came back.

And now those years I spent in Provo don’t haunt me anymore. I’m equipped to handle the strange ambivalence of loving a place that didn’t always love me back, a place that gave me both unspeakable pain and enduring pleasure.

I don’t feel a need to resolve that contradiction, to tie it into a neat bow. After all, love doesn’t have to make sense — at its most powerful, it often doesn’t.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra