After the long flight from Dubai, I made my way to the hotel information desk in Heathrow Airport. “Could you tell me where Half Moon St is please?” The clerk behind the desk ignored me, more concerned with chatting to her co-worker than a rumpled visitor.

I knew the hotel was near Green Park, central for both sightseeing and the meetings I had later that week. But I had never heard of Half Moon St. I posed the question a third time.

She looked dismissively at me and with a lazy gesture unfurled a map. A thin finger jabbed at the map, at a one-block street running off Piccadilly. “Thank you.” It rolled off my tongue, dripping sarcasm.

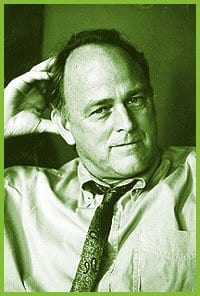

Weeks later, as I read the biography of First World War poet Wilfred Owen, Half Moon St cropped up once again. It was on this street that Robert Ross introduced Owen to the gay London literary scene. Ross was a Canadian. Yet few of us know about him, despite his pivotal role in the life of Oscar Wilde.

Ross’ maternal grandfather, the Honourable Robert Baldwin, had been joint premier (with Hippolyte LaFontaine) of the united Canada. His father, the Honourable John Ross, was Attorney General of Canada. Ross’ family had moved to Europe for health reasons and stayed, although they made trips back to Canada now and again. Robert Ross was born in Tours, France in 1869.

How Ross came into Oscar Wilde’s life is a matter for speculation. One version goes it resulted from Wilde’s lecture tour of Canada in 1882. Wilde’s tour was to be a grand success, particularly in Ottawa at the Russell Hotel. A young female Ottawa artist in the audience approached Wilde after his talk, seeking his assistance to gain entry into the art world of London. He agreed to help her. She, in turn, gave Wilde Ross’ address in London, urging him to contact her young friend with literary aspirations.

The long and the short of it was that Wilde did. Ross moved into the house of Wilde and his wife Constance. It was there, in 1886, that 17-year-old Ross inducted the 32-year-old Wilde into the intimacies of male sex. Their relationship was relatively brief. Wilde developed a taste for slim-hipped young men of a rougher countenance, which continued even during and after his passionate affair with the young narcissistic poet Lord Alfred Douglas.

Ross remained in love with Wilde throughout his life, becoming his confidante. Wilde turned to him in times of emotional turmoil during his affair with Lord Alfred. It was Ross who cautioned Wilde against taking Lord Alfred’s father, the Marquess Of Queensbury, who had accused Wilde of being a sodomite, to trial. Wilde ignored Ross’ sage advice. Nonetheless, Ross stood by Wilde throughout his trials in 1895. When imprisonment seemed imminent, Ross counselled Wilde to flee to Europe. When the sentence came down, he retrieved manuscripts and key personal papers of the author from his house before it was turned over to bankruptcy bailiffs. He raised almost enough funds to cover Wilde’s main debts, but just not enough.

Throughout Wilde’s imprisonment, Ross would visit, acting as a go-between, conveying messages from Wilde to Douglas or to Wilde’s wife who had gone to Europe. He prepared Wilde’s refuge in France, to which the author went upon his release from prison. There, Ross encouraged him to write, overseeing his last works. Ross was Wilde’s literary executor and after Wilde’s death in 1900, Ross kept his works in print despite a ban that had been placed on them. Ross commissioned the artist Jacob Epstein to create the monument that would mark Wilde’s final resting-place in Paris. It was there that Ross’ ashes were placed on the 50th anniversary of Wilde’s death, in a secret cavity he had asked to be put into the design so he would forever lie with the man whose life he had changed irrevocably.

Ross’ lodgings on Half Moon St were a salon in the early 1900s that saw the coming and goings of famous and soon-to-be-famous writers, particularly homosexual authors. At that time, gays in London lived lives of subterfuge, fearing exposure and imprisonment. The aftershock from the Wilde trial in 1895 still reverberated. Yet there, at the centre of it, was Ross living openly as a gay man, just as he had when he stood by Wilde and as he continued to do until his death in 1918.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra