Newsflash: Canadians are still dying of HIV/AIDS. The killers from the early days of the epidemic are still around – infections like PCP (pneumocystis carinii pneumonia), and KS (Kaposi’s sacroma). But to these have been added deaths from various types of cancers, heart attacks, strokes and diabetes.

That is what doctors will tell you, based on what they’re seeing among their patients and in hospitals. In Ontario these deaths are not being formally tracked, so there is little solid data on causes of death.

“That information is hard to get at,” agrees Ahmed Bayoumi, research director at the Ontario HIV Treatment Network. Bayoumi says he’s made efforts to link an Ontario database of people with HIV/AIDS with death records, but has run into roadblocks because of confidentiality concerns and technical issues.

Health Canada officials can give minimum figures for the number of people in Canada whose deaths are AIDS related – 89 in 2002 compared to 1,497 in 1995, which was the worst year for deaths. But they don’t have information on what people died of and they caution that AIDS cases are underreported and so are AIDS deaths, since it’s not mandatory to report them.

If you’re HIV-positive (but don’t have AIDS) and die, or have AIDS and die from something like a heart attack or liver failure, there’s a good chance you won’t show up in the federal statistics.

Alex Klein, a family doctor who has treated people with HIV/AIDS in Toronto since ’81, says “the truth is that among those who are on HAART (Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy), we’re not seeing a lot of deaths.”

But people with co-infections of hepatitis B and C are at a heightened risk of liver disease, he says. As people live longer, their family history of illness and habits such as smoking, combined with the impact of the HIV infection itself and the drugs used to treat it, can leave them particularly vulnerable to conditions like heart disease, diabetes and stroke.

Until recently, doctors haven’t spent a lot of effort counselling people to change some potentially harmful lifestyle habits like smoking, drinking and eating fatty foods, he says. “The attitude was, ‘You should live so long.’ And there are socioeconomic considerations: if you’re on a public disablity plan, you might not be able to afford to eat better food or join a gym.

Meanwhile HIV-positive people in the hard-to-treat population – including injection drug users, the homeless, refugees and undocumented people who lack access to health care – are still dying of the classic AIDS opportunistic infections, says Gord Arbess, who works at the clinic at 410 Sherbourne St.

So are those who have become drug resistant, or have chosen to go off medications, says Kevin Gough, an infectious diseases specialist at St Michael’s Hospital who is also on the board at Casey House AIDS hospice. Gough has recently had patients with PCP, and those dying as a result of progressive HIV wasting disease, liver failure and KS in internal organs.

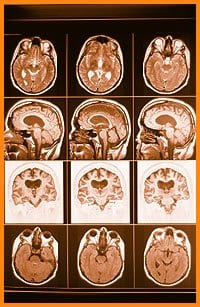

“The old opportunistic infections are not gone. We still see the traditional causes of death and a whole new set of complications,” he says. Those newer complications include liver cancer, non-Hodgkins lymphoma, brain lymphoma and heart disease. There are also more bone problems and more osteoporosis – not themselves fatal, although a hospital admission for a broken hip can lead to other complications.

Suicide is another cause of death among the HIV-positive population and Arbess says that in the past year two of his patients have killed themselves. (A two-year-old Ontario study of 32 people with HIV/AIDS found the majority had decided to pursue assisted suicide as an option because of their physical deterioration and their loss of community.)

In British Columbia, fully one-third of BC residents who died of HIV-related causes had not received treatment for HIV infection, according to a recent study. Those who didn’t get treatment were mostly First Nations people, female, poor and/or living in Vancouver’s drug-ridden downtown eastside, according to the study from the BC Centres For Excellence In HIV/AIDS.

In Ontario, official estimates state there are about 22,000 HIV-positive people, of whom about two-thirds, or 14,200, have been diagnosed, according to University Of Toronto epidemiologist Robert Remis.

Just over half of those who’ve been diagnosed (about 8,000 people) are on drug therapy, says Remis. (British Columbia, which provides AIDS drugs free of charge, maintains a centralized system and can track people with HIV/AIDS much better than Ontario. In Ontario, people may have private drug coverage, have social assistance drug coverage or receive partial coverage based on income from the Trillium drug program.)

Klein is concerned that the pendulum may have swung too far away from treatment with protease inhibitors. The “hit early, hit hard” approach to drug therapy, which saw newly infected people going on heavy duty drugs, has been discredited, he says.

Increasingly Klein sees young gay men who resist treatment, even when it is advised, because they are concerned about developing lypodystrophy, a disfiguring side effect of the drugs which “outs” many people on AIDS drug treatment.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra