Last year, I needed to find a new place to live. I had been sharing—squatting in, really—a three-bedroom apartment with eight other queer folks who were kind enough to let me stay with them just before the pandemic hit Nigeria in March. While that housing arrangement provided me an immediate queer community and allowed me to save up enough to get a better place, it was also an arrangement I knew I couldn’t keep up for long.

The main problem was personal space, of which there was very little. There were small pet peeves—from someone borrowing my favourite work bag without permission to listening to three televisions playing at the same time most nights—that started to grate on me. And so, when the rent was due and everyone else was getting sick of the arrangement, it made perfect sense to move.

I began my search last November for a space that would provide me with a much-needed sense of privacy. I did not mind if I would have to share it with a person or two; I just wanted it to be spacious enough that everyone had their own space. Rent in Lagos is notoriously expensive, and few landlords allow you to pay in installments, so I tried not to get my hopes up. But contrary to my expectations and with the help of a friend, it took just one week to find a possible housing option—one I didn’t even need to share.

When I first stepped foot in the small, two-bedroom bungalow apartment I now call home, I didn’t have to think twice about whether or not I would take it. I felt an acute sense of safety the minute I walked in—there was a quiet ambiance about it, and I couldn’t help but start imagining how I’d make it mine. It was what I was looking for but had been too afraid to dream of.

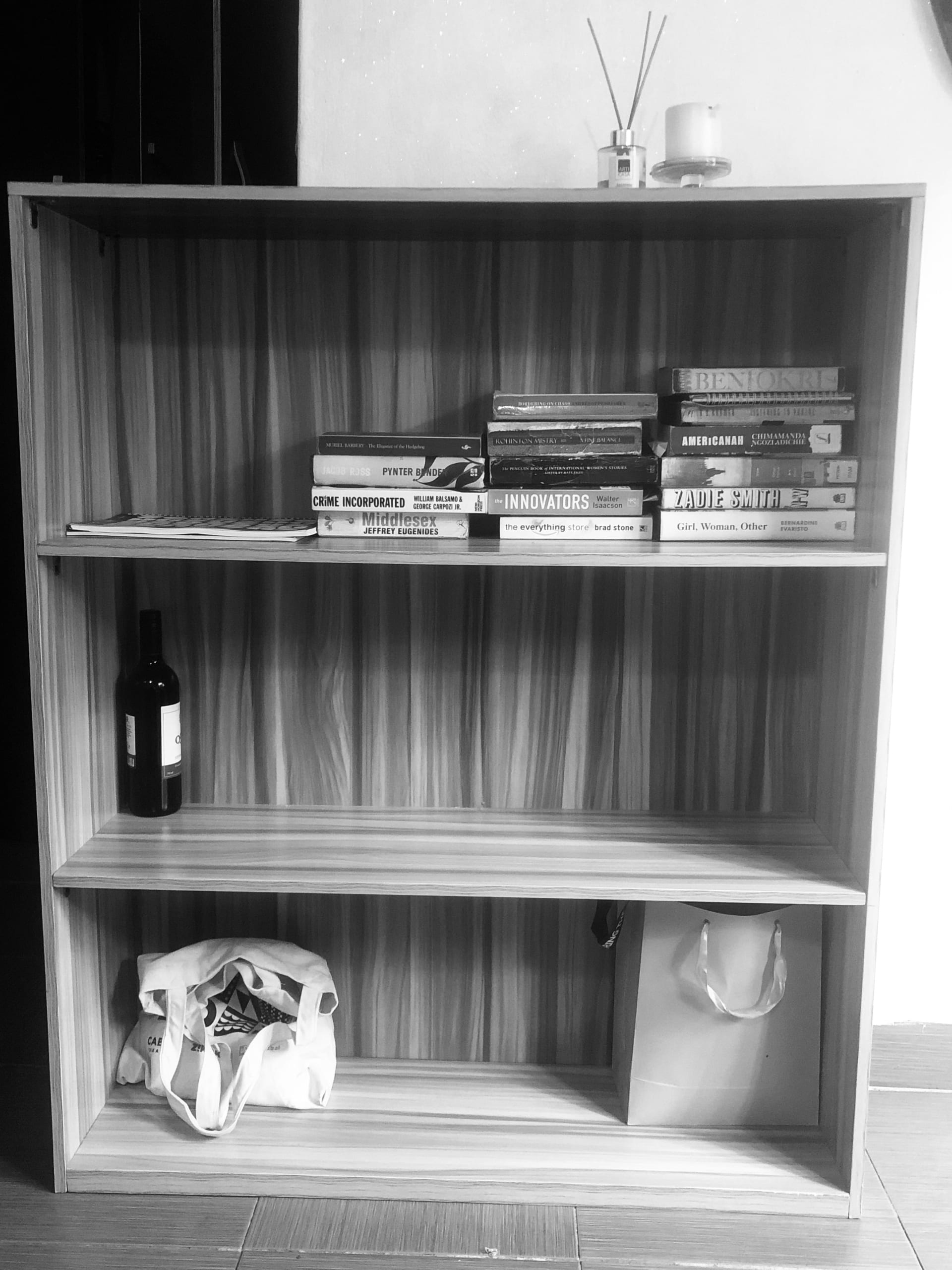

Credit: Courtesy Nelson C.J

I have come to love the smallish-bigness of this place. Like many one- or two-bedroom living spaces scattered across Lagos, my flat has a clean and intentionally minimalist design. The sitting room is only big enough for a couch and a simple, centre table made from light wood. The kitchen is right beside the sitting room, so small that four people might not fit at a time and yet able to accommodate the rancor of my chaotic cooking (which mostly involves fried plantains and egg-soaked yams). Then there is my bedroom, a short walk from the sitting room and similar in size. Everything in my space is there with intention—there isn’t much room to have just anything sitting around on the shelf or taking up space below my window.

“The apartment was what I was looking for but had been too afraid to dream of.”

As a 20-year-old, my apartment feels like a personal victory. I never thought I would be able to afford a home like this for a long time. And as a young queer man, the apartment feels like my own personal oasis. I’ve lost count of the many times I’ve returned home with a sigh of relief. I feel it rise in my chest as I turn the key in my lock and shut the door against the world. I feel it lying on my bed on a lazy weekend watching Grace and Frankie. I feel it when I listen to the quiet around the house—no TVs or chatter, just my rechargeable standing fan whirring. I feel it when I remember I can go to my sister’s house, a place where I cannot truly be myself, on my own terms; I now have a safe space to turn to whenever I need it.

In this small-roomed sanctuary, I can exist in a space where my queerness is not policed. I can play the gayest music or watch the queerest television shows without the fear of a family member looking over my back. I can speak with my friends on the phone without making mental notes to check my language or find other crafty ways to say what I want to say. As minute as those actions might sound, they mean something to me, a queer Nigerian who has grown up with an awareness that I shouldn’t exist as I do. And by virtue of living in Nigeria, a country where violent homophobia has been legalized and where the fundamental right to gather with whomsoever we please attracts a lengthy jail term, personal space is everything.

Credit: Courtesy Nelson C.J

I know I am lucky. For every queer person like me who can afford places of our own, there are many others who are either stuck with family or housemates who wouldn’t hesitate to harm them. I can invite people to my space and curate a sense of community whenever I choose, but that is not an accessible reality for many queer folks I know. Housing and health care are also tightly linked. Those in wealthy neighbourhoods can access much higher levels of care than those in poorer areas, where most queer and trans people live.

I know I am lucky: I wake each day in my new apartment with a swelling sense of gratitude. I can only hope that soon this sort of freedom will be more accessible for other Nigerian queer folks. It’s the least anyone should have to ask for.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra