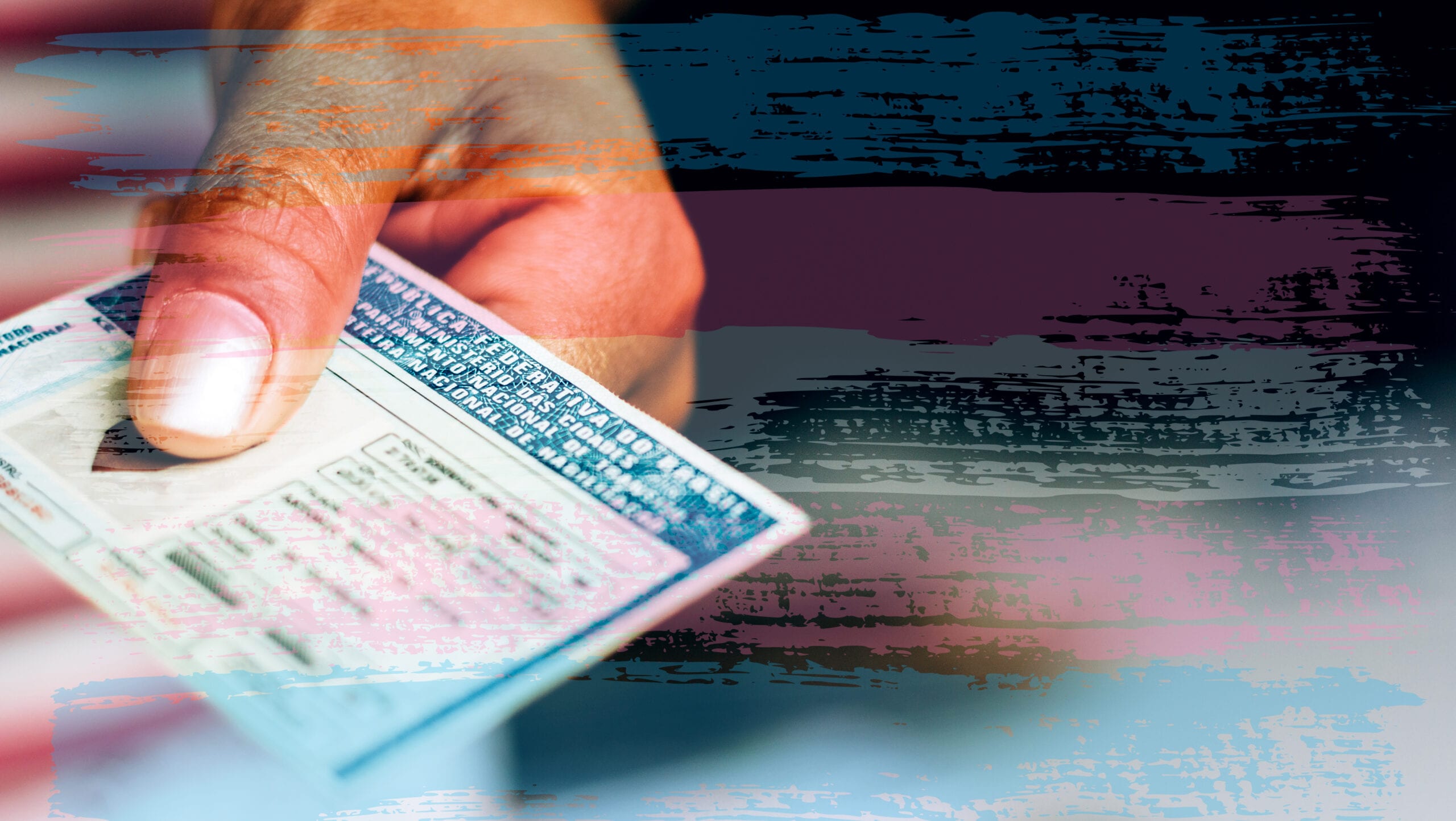

Could having identification that match your gender and name improve your health? A new study thinks so.

The study, published earlier this month found there may be a link between access to identification documents, like health cards and drivers licences and more positive mental health for trans people. Published in the Lancet Public Health Journal, it found that individuals whose IDs l reflected their correct name and gender marker had lower rates of serious psychological distress and suicidality.

The study used data from the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey to examine the relationship between correct names and gender markers on IDs and mental health. Of the 22,286 participants included in their sample, 45.1 percent had their preferred name and gender on none of their documents, 44.2 percent had them on some, and only 10.7 percent had them on all of their identification documents.

“Only 11 percent of people in the study had all of their IDs reflecting both their name and their gender, and yet that group was at markedly lower risk of psychological distress, suicidal thoughts and suicide planning”, says Dr. Ayden Scheim, a social epidemiologist at Drexel University and co-author of the study.

The study found that having all IDs accurately reflect names and genders was associated with a 32-percent reduction in serious psychological distress and a 22–25 percent reduction in suicidal ideation and suicide. Meanwhile, only having some correct ID documents correlated with smaller reductions in psychological distress and suicidality. These findings demonstrate that legal gender affirmation is a structural determinant of health for trans people, who already face massive inequities and discrimination.

While this study doesn’t prove that access to ID that accurately reflects your name and gender directly improves mental health, it does demonstrate that there’s a relationship between the two, Scheim says. For many trans people, this is no surprise.

“I see the positive mental health impacts of people just getting their ID. It really does reduce the stress that they deal with” says Taryn Husband, a trans man based in Ottawa whose identification documents don’t match his gender. “It’s about safety. Correct identification can protect you when seeking services. You don’t need to have the extra level of stress going to your doctor, your job or your university”.

“Part of the issue is that ID is a document of who you are and having that reflect something that isn’t true is really disorienting,” says Niko Stratis, a trans activist and writer based in Toronto. “I have a couple pieces of ID that aren’t correct and it’s like looking at a bad memory— it takes me back into those memories and being in a very bad place mentally” said

Dr. Scheim emphasized the negative impacts associated with incorrect name and gender information on IDs. “There’s a risk of being outed at a bar or a bank, a risk of harassment or denial of services.”

Negative experiences with IDs that don’t reflect your gender and name can have serious impacts on trans people. “One-third of people in our study had had a negative experience presenting ID that didn’t match their name and gender, but every trans person has heard a story of someone who had a negative experience related to ID and that fear can cause real distress and make people worried about accessing essential services” Scheim says.

Despite significant progress in Canada to make it easier for individuals to change their names and gender markers on identification, there are nonetheless still serious barriers. In most Canadian provinces, legal name changes include a fee of approximately $150.00, and changes to the gender marker on drivers licenses and health cards often include a similar fee. In some provinces, such as Ontario, in order to change your gender marker on your driver’s license, you need a letter from either a psychologist or doctor who has assessed you and supports your request to change your gender marker. Changing the gender marker on your birth certificate is similarly complicated, and the process and cost varies across provinces.

In comparison, while Canada certainly has far to go on facilitating legal name and gender marker changes for trans people, the barriers in the United States are often even more arduous, and vary more depending on the state you live in. While some states have phenomenal, low-cost and low-barrier policies, others require individuals to provide proofs of surgery, court orders and letters of support from licensed healthcare providers, which can significantly increase both the barriers and costs for trans people.

“It’s a huge financial commitment to change all of your identification documents. You have to pay for a new birth certificate, a name-change fee, a new passport, new provincial documents and so much more,” Husband says.

Changing your gender marker and legal name shouldn’t be as complicated as it is, Stratis says. “If we want to improve people’s lives, it should be easier for them to make these changes rather than creating all these ridiculous barriers.”

Given that almost half of trans people in Canada live below the poverty line, according to a recent report published by Trans Pulse Canada, the financial cost associated with changing all of your identification documents to reflect your correct name and gender is likely a significant barrier.

Jan Lukas Buterman, a trans man, researcher and graduate student at the University of Alberta said that this study is crucial because it backs up what trans people have always known—and highlights why it’s important to have empirical data to validate experiences.

Buterman, however, also raised the question of why identification documents even have gender on them in the first place. “What does an ‘M’ or an ‘F’ actually mean? What purpose do they accomplish? It’s literally an opinion that someone says and puts on your legal document.”

Scheim agreed and emphasized the need for a discussion on the relevance of gender markers on identification documents, saying that “a photo is much more reliable than a gender marker can ever be,” but emphasizing that in the meantime, getting correct names and gender markers should be made easier.

Moving forward, Scheim hopes this study will demonstrate to governments and policy makers that there is a correlation between positive mental health and correct names and genders on identification documents. He hopes this study encourages advocates and policy makers to remove unnecessary obstacles, reduce costs and help make sure that trans people who want to change their names and gender markers can do so.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra