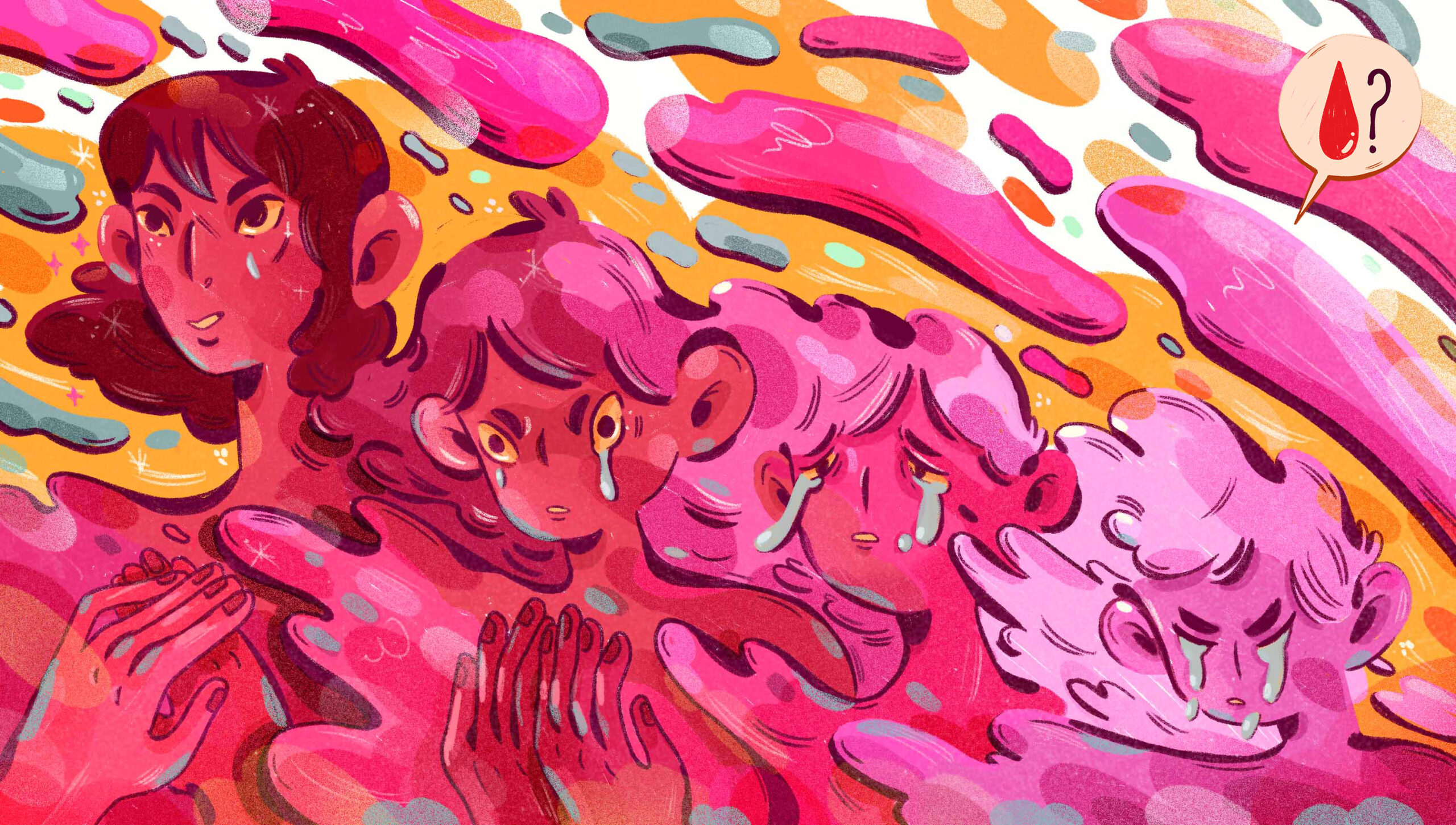

This story is part of Seeing Red, a month-long series exploring periods from an LGBTQ2 perspective.

The day I got my period, I was in the washroom in our new apartment in Bur Dubai. I already knew what it was: our maid back in Calcutta (now known as Kolkata) had told me all about it shortly before we moved. So at the age of 10, instead of freaking out about the blood in my underwear, I called for my mother.

What made the monthly ordeal repulsive to me was the act of getting rid of dried blood from my underwear. I had to wet the rust-like stain first, then sprinkle it with detergent powder, wet my underwear yet again until the detergent soaked in and then scrub the stain with all the strength I could muster. The blood never completely disappeared. Sometimes I felt so lazy about the washing that I would leave a collection of stained undies piled behind my clean ones in the cupboard. I was found out, of course. My mother called me nonkra meye — “dirty girl” — and I was never allowed to forget the incident. It’s been added to her repertoire of family stories.

My ordeal, as I like to think of menstruation, lasted only until I was 12. It was then that the monthlies began to dwindle in time and frequency. A five-day ordeal became three, then two, then appeared only every two or three months. The last time I was ever visited happened after a gap of six months, then my period ghosted me forever.

My middle class parents did what they knew best and turned to doctors. The summer of 1998 was filled with visits from one doctor to another. The tests were numerous: ultrasounds, blood tests, even gene counting. I was picked and prodded, mostly by older male gynaecologists, all over Calcutta. They agreed that my sexual development was “normal” for my age; I had the breasts and pubic hair to prove it. They agreed that my uterus was intact. They also agreed that I had premature menopause.

“It’s simply this,” a smug white-haired male doctor said while seated in his air conditioned office in Salt Lake, a posh neighbourhood in Calcutta. “Her body had limited eggs, and now those eggs are gone.” The matter-of-fact pronouncement was a death sentence for my parents. They saw me as incomplete, someone whose worth, at 12, had lowered; they saw my diminishing value in a future marriage market where no men would bid on me. I was put on prescription birth control to regulate my hormones and, essentially, my periods. My body was made to simulate the ordeal I thought had ended. Now, not only would I bleed, but I would also have to take pills for 21 days each month. The pill was also supposed to regulate my estrogen production and maintain the physical and biological “normalcy” of being a woman. Every time I popped one of those pink pills, I imagined myself as a sick person, somebody relegated to being ill for the rest of their life.

“What happens when there is an undesired excess of estrogen in your body from the age of 12?”

What happens when there is an undesired excess of estrogen in your body from the age of 12? As a child, I was not consulted. That estrogen was supposed to be good for me. Instead, I began to hate my body and the way that it changed. I began to hate my breasts, which seemed abnormally large for my figure. My mother said this discomfort came from the fact that I was a teenager, and my body was changing. But my body changed too fast. I was the first girl in my Grade 6 class to wear a bra. I had to endure a whole year of other girls gossiping about it until their own breasts started to grow.

As I grew older, I tried to see my breasts as other boys did. I tried to sexualize them. I held them together and watched the deep cleavage form in the mirror while I pouted like a sexy Mamta Kulkarni on the cover of a Bollywood film magazine. But the otherworldly lumps still felt like they belonged to someone else. I used clothes to disappear, donning a sports bra over my regular bra, then an oversized shirt or T-shirt over jeans or shorts. This became my staple, a uniform that lasted well into my mid-20s. In retrospect, I now realize that my body dysphoria had less to do with my teen angst, and more to do with how my body was no longer mine.

After I turned 22, the discussion at home shifted to how I would get married. No man would want me because I couldn’t conceive conventionally (my inability to naturally menstruate often referred to as a “problem” by my parents). I began to feel like less of a woman, like what was biologically supposed to work was broken and now needed constant fixing to maintain a semblance of normalcy. The pills were a reminder of this brokenness, as were my parents. Now that my period was gone, losing my “natural” birth-giving abilities seemed to have a huge stake in my femininity and desirability as a future wife, and taking the pills became a dirty secret. Ovarian failure was my secret, my problem.

“I realize that my body dysphoria had less to do with my teen angst, and more to do with how my body was no longer mine.”

My silence and complicity became part of a mutual contract I was somehow coerced into signing with my parents. They were conflicted, torn between optimism and fear, trying to protect me from both disappointment and heartbreak. Sometimes my parents would try to convince me — and by extension themselves — that ovarian failure was quite common these days, and adoption was an easy solution. Other times, they would tell me not to reveal my secret to anyone I was dating until I was absolutely certain of the strength of our relationship.

Carrying my secret, which was by default my parents’ secret, and, alongside it, taking the pill, cost me my mental health. It would be at least a decade before I would connect my depression to a possible side effect of the pills, a symptom that is increasingly being discussed publicly. Yet I have been taking them for so long that stopping could lead to fatal blood clots. I am 33 now, and still taking those pills.

I connected with the love of my life over email. In 2012, I had read his poem in an Indian feminist magazine and decided to reach out. We became good friends and by the time we fell in love in late 2015, I felt it was time to tell him my secret.

Over Skype in mid Nov 2015, a month before I was to fly to India and meet him in person for the first time, I told him about this “problem” that had made me feel like less of a woman. “If this is going to cause a problem in the future, you can back out now and I won’t hold it against you,” I said. He took a drag of his smoke and replied, “If we want kids, we can adopt.”

“I was able to recontextualize my ‘problem’ as a happenstance, something that just was.”

When I told my parents about us two months later they asked, “Does he know?” I nodded. And then, “What was his response?” My partner’s answer to the problem they had spent years worrying about helped our relationship move forward at a faster rate, an urgency lay in my parents’ desire to see me get married. “He is such a good boy,” would become a refrain in my household — the previous narrative of my “problem” replaced by their daughter’s union to this “good boy.”

Throughout all this, I was still dealing with body dysphoria but my relationship eventually helped me come to terms with it. Here was a person who finally knew all my secrets and accepted me in spite of them. I could be myself, my whole self, and exist within my femininity that lay outside conventional understandings of womanhood without feeling like an outsider. Finally, I was able to recontextualize my “problem” as happenstance, something that just was. It was only after our wedding date was decided upon by both of our parents’ in mid-2016 that I finally came out as genderqueer to my mother (and later to my sister and father).

It was only through my partner’s acceptance of me that I was able to accept myself and become more true to who I am. Not feeling as if I was broken or that I had a problem — that I could be loved for who I was and love myself — helped my mental health improve. For the first time, I feel in control of my body and of who I am as a person.

I don’t know if I want kids yet, but my partner and I haven’t ruled out adoption completely. I do know that whatever we choose, I’m on the path to becoming my true self. I see my body as neither male nor completely female — it is a composite of both, like a biological Schrödinger’s cat. I see myself outside the gender binary, somewhere in-between a man and a woman; an androgynous Ardhanarishvara.

This in-betweenness feels like it fits me right.

This story is part of Seeing Red, a month-long series exploring periods from an LGBTQ2 perspective.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra