In the mid-’90s, one person in British Columbia died of AIDS every day. Two more were diagnosed with HIV daily. The epidemic was more severe in B.C. than anywhere else in Canada.

That history is why, in the 30 years since, the province has revolutionized care—opening the nation’s largest largest HIV/AIDS research and treatment centre, pioneering the treatment as prevention strategy and becoming the first province to completely cover the costs of treatments and the highly effective HIV prevention medication PrEP for those at risk of contracting the virus.

Yet this robust infrastructure is now preventing people with HIV in the province—many of them LGBTQ2S+—from receiving the care they want.

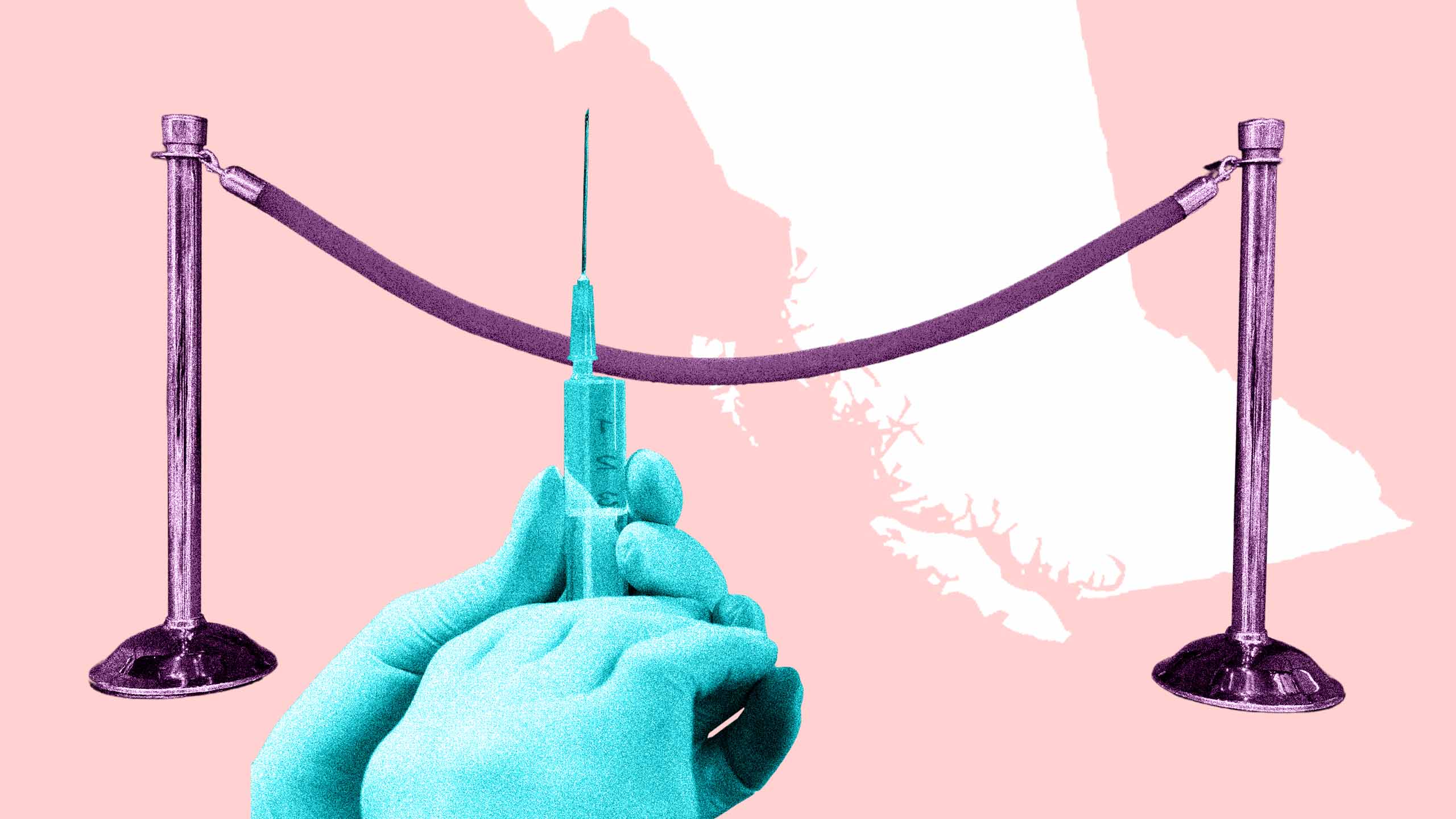

A new advocacy campaign by AIDS Vancouer is pointing out that this is the case with the long-acting, injectable HIV medication Cabenuva. Cabenuva is a combination of two HIV medications, typically taken orally, that help keep the amount of HIV in someone’s body low—preventing that person from developing AIDS or transmitting the virus to another person. Approved for use in Canada three years ago, B.C. remains the only province that has not made Cabenuva widely accessible to its residents.

“I’ve worked with people who have been looking forward to injectables being a possibility for many, many years,” says Sarah Chown, executive director for AIDS Vancouver. “We really want to make sure this option is available for people to choose.”

What is injectable HIV treatment?

Treatment for HIV involves taking a combination of medicines, most of which aim to slow the rate at which HIV makes copies of itself in the body. While there’s no cure, a lower viral load allows a person’s immune system to remain strong (preventing them from developing AIDS), and limits the virus’s ability to move from one person to another during sex. Sex is still the most common form of transmission, which contributes to the fact that half of all HIV cases in Canada are among gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men.

In the earliest years of treatment, people with HIV had to take multiple (and costly) pills a day, many of which caused intense side effects like liver problems and low blood-cell counts. Over decades, these treatments have become simpler, more effective and better tolerated. Today, someone living with HIV can get their entire regimen of medications in one daily pill.

Then came Cabenuva. A combination of two HIV drugs, Cabenuva is injected once a month for two months, and then every two months following. Though not the only HIV treatment option that involves injectables, Cabenuva is currently the only available one that can completely replace daily pills—and Canada was the first to adopt the treatment in 2020, with the EU and U.S. following shortly after.

Why do many people prefer injectable HIV treatments over pills?

“Taking a daily pill is a huge burden for lots of different reasons,” says Chown, citing a major demand for injectable medication among young people—especially those who have had HIV since birth. “I’m talking to teens and tweens who want to go on a school trip or sleepover and, because of HIV stigma, don’t want to tell their friends or be caught taking medication.” Another priority group for AIDS Vancouver and their partners is women, both cis and trans, who may face violence from a partner if their HIV pills are discovered.

Because pills need to be taken at specific times of day or with food, it’s harder for people to keep this personal medical information discreet, Chown explains. This is backed by a 2021 global survey of nearly 2,400 people living with HIV which found that about 40 percent are worried that their pills will expose their HIV status, and a third are stressed about the need to take pills every day.

“People who work long or irregular days … people who can’t get home on time … people who experience a psychological toll or difficulty based on trauma around their status. All of this makes it harder for thousands of people to take their medication every day.”

Why is British Columbia the outlier in Canada when it comes to injectable HIV treatments?

Since being approved by Health Canada in March 2020, most people can access Cabenuva through their doctors—sometimes at no cost, depending on coverage. This includes Canada’s other most-populous provinces of Ontario, Quebec and Alberta.

People in B.C., however, need secondary approval through the B.C. Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS. Spokespeople from both the Centre and the province’s Ministry of Health tell Xtra that this means Cabenuva is, in fact, available in B.C., and that their oversight is because of the “specific clinic and implementation considerations” of the treatment, as well as their desire to “maximize patient and population health outcomes.” This secondary approval also applies to communities who would have had access through federal drug programs, like Indigenous people and inmates.

Chown, however, is quick to point out that the Centre’s guidelines for approving Cabenuva are incredibly limiting. “We’ve had a really hard time figuring out who the guidelines actually apply to, and we don’t know of anyone who has been able to successfully access the injectable treatment option through those guidelines.”

This is largely due to seemingly conflicting rules, Chown says. For instance, the Centre says they’d approve Cabenuva for people who have both a low viral load (meaning they’ve been taking HIV medications consistently) and an inability to take oral medication (like being diagnosed with a swallowing disorder).

“You can’t really get to a controlled viral load without being able to swallow the daily pills, so it’s really hard to see how those two things could both happen at the same time.”

The Centre’s spokesperson confirmed that people in B.C. have been successfully approved for Cabenuva, but stopped short of saying how many people that applies to or addressing Chown’s specific concerns.

Why should British Columbia expand access to injectable treatments?

At the height of the HIV epidemic, the Centre’s centralized powers were a good thing. People were dying, so decisions and resources needed to be allocated quickly, and the Centre was established to step around broader homophobia and racism in the province—providing care through their own channels.

But their withholding of Cabenuva has been prescriptive and paternalistic, says longtime HIV advocate Wayne Campbell. “It’s shameful, especially considering B.C. was a leader for so many years.”

As for why the Centre won’t release Cabenuva more widely, Campbell—who works with AIDS Vancouver and is part of the campaign—is unsure, but suspects it may, like most things, have to do with control and money. “With the Centre’s monopoly on everything, they are watching their budget numbers. That’s been one of their longest-standing arguments, that their budget is stretched thin as it is.”

The Centre’s spokesperson, however, emphasized that their control over access is to manage the “safety and efficacy profile of the drug.” But Campbell also highlights how injectable treatments would save costs elsewhere in the healthcare system, specifically when it comes to clearing up capacity.

“You’d go into a doctor’s office for 15 minutes, get a shot and you’re done for a month or two. We won’t need to sit in pharmacy offices for so long getting pill refills.”

What happens now?

The Centre’s spokesperson tells Xtra that as evidence and experience around Cabenuva accumulates, they’ll adjust the approval criteria as necessary.

Chown is hoping to speed up that process, launching a letter-writing campaign directed to B.C.’s minister of Health, Adrian Dix, and other members of his government. Her hope is that the government can put some pressure on the Centre to, if not change the approval process, then to communicate more openly with representatives of people living with HIV.

“We’ve asked repeatedly for the decision-makers to tell us why they’re saying no,” she says. “We’re not asking for everyone taking pills to be given injectables. We’re asking for people who want injectable medications to have that option in the way they do in most of the rest of the country.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra