Walking into Supporting Our Youth’s (SOY) boisterous Monday night drop-in for the first time can be an overwhelming experience for anyone — much less a socially awkward twentysomething who’s new to Toronto and has never met another queer person before.

On one Monday night in April there are more than of 25 people crowded in a room on the second floor of the Sherbourne Health Centre around two rectangular tables or crammed onto adjacent couches, chatting over plates of steaming curry chicken and rice; some silently flit through the menu features on their mobiles with equal interest. One or two dart out of the room somewhat dramatically, phones glued to ears. The night is slightly atypical. Both of the drop-in’s well-liked coordinators have recently left, and the mood is anticipatory — or maybe it’s just loud.

Over dinner one girl complains to a group coordinator that, lately, she’s feeling inundated by heterosexism, while another guy complains his upset stomach is holding back his usually voracious appetite. Others sit quietly and listen as intern Lexi Linden commandingly announces the evening’s agenda: dinner, followed by a discussion about the coordinator situation and then a frank round of sex questions or, for those who prefer more PG-rated fare, a screening of the Brit boy-turned-ballerina movie Billy Elliot in another room.

If you don’t know where to look upon entering, chances are your eyes will meet those of 25-year-old George Grant who is standing behind the serving table, pointing a serving spoon anxiously at the bowl of tofu vegetable curry on the table, eyebrows raised expectedly as if to say, “Do you want something to eat?” The drop-in is busiest between 6:15pm and 7pm when dinner is served. By the time plates are a cleared several people are gone.

When SOY started in 1998 it filled a void. At that time there were no service organizations aimed at queer youth in Toronto, age restrictions kept many out of the Church St bar scene and, even when they were allowed in, social taboos kept young and old segregated for the most part.

In the early days SOY attracted many well-to-do high school and university kids whose big issue was coming out. Since then organizers have watched the demographic shift dramatically toward multiply marginalized queer youth: black youth, trans youth, street-involved or homeless youth, immigrants and refugees. As SOY prepares to celebrate its 10th anniversary with an all-ages party at Circa on Thu, May 8, organizers and staff say its social groups are needed now more than ever.

“I always think it’s amazing that youth who know nothing about the community have the courage to walk through the door,” says Leslie Chudnovsky, coordinator of SOY’s drop-in and mentoring program. “You never know when you’re going to an organization who’s going to greet you.”

At the drop-in Grant pronounces himself the unofficial welcoming committee. It’s easy to believe. Dressed in a collared shirt and black trousers, his broad smile is certainly friendly. But if you take the bait you’re in it for the long haul — behind the smile are a slew of opinions. During dinner he’s at the table you want to be sitting at; he’s the focal point of a lively debate about which character on The L-Word is the hottest, his finger waving in the air at his peers like Mariah Carey hitting her fourth octave. “It’s the one thing we can discuss and everyone, young and old, is right in there,” he laughs. When he leaves the room it’s noticeably quieter.

Since he started coming to SOY seven years ago Grant says his attitude has completely changed. Once “your typical snooty fag” who hung out with “other snooty fags with rich daddies and no education,” he’s now someone his family and friends frequently turn to for advice.

“As a kid I did not display emotion very well and I didn’t wear much colour so they used to call me ‘Robo ’82,'” says Grant, because he was born in 1982. “Now I wear colour,” he says, dramatically gripping the seam on his slightly oversized red-striped black shirt, “and I’m very emotional.”

These days he spends much of his time taking care of his grandfather, who’s been diagnosed with cancer. He’s also applying to George Brown College’s nursing program.

“Before I came here I didn’t believe in the clash of classes,” he says. “I came from a white-picket fence house in Coxwell and Danforth. This place was completely going against everything my family stands for. But I’ve since learned diplomacy, tolerance, empathy. I believe that came from here.”

Though it’s geared toward youth up to 29 SOY is also designed to give adults the opportunity to have relationships with young people through a mentorship program similar to Big Brothers and Sisters. During the drop-in, for example, adult mentors are on hand and some join in on the evening’s workshop or discussion.

“Almost everybody when I ask them why they want to be a mentor gives me one of two reasons,” says Chudnovsky, “and it’s really the flip of the same reason: either they had nobody to talk to when they were coming out and what a huge difference it would’ve made in their lives or because they were fortunate to find somebody and it changed their lives in a positive way.”

***

Fifteen years ago the Toronto Coalition for Lesbian, Gay and Bisexual Youth — a network of social workers, community activists, healthcare providers and educators — decided to tackle the issue of youth alienation. With underage events hard to come by in Toronto — and not just in the queer community — the group struck a committee and embarked on a series of community consultations.

It was a time when many of the people hoping to create new, youth-focused spaces weren’t out in their own workplaces, says Bev Lepischak, SOY’s programs manager. She was working for Toronto Youth Services in 1993 and saw first hand how the same homophobic environments that kept service workers in the closet also marginalized queer youth looking to these agencies for help. Nor did the gaybourhood offer a safe haven: The perception was that Church-Wellesley business owners increasingly viewed youth hanging around on the street as a nuisance.

“Youth were very much on the margins of that community and the interactions between youth and adults that did happen generally happened in bars. For a lot of youth, it just felt very exploitative,” says Lepischak.

A common attitude among SOY participants is apathy toward the village and the gay bar scene, and for many the upcoming anniversary party at Circa will be their first glimpse inside the multistorey megaclub. Others just can’t afford the luxury.

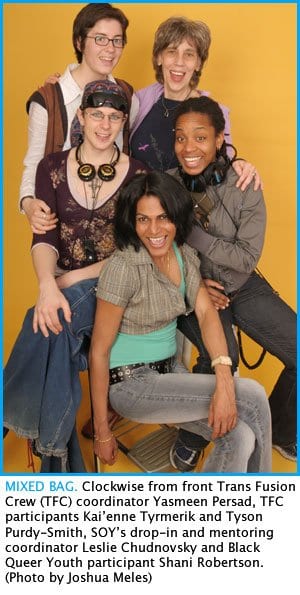

“For meeting people you’ve got bars, clubs and maybe the odd chance encounter at a coffee shop,” says Kai’enne Tyrmerik, a frequenter of Trans Fusion Crew and Monday night drop-in. When the 22-year-old left St Catharine’s in February 2007, Tyrmerik had little more than a backpack and wound up spending several months in a homeless shelter. “All the social places involve money and if you’re not a person with a lot of disposable income you’re going nowhere. But a place like this is somewhere you can come, chill, meet people and not have to spend any money.”

When SOY began, concerns were raised that queer adults volunteering for youth programs would be seen as predatory. “There was a worry the Toronto Sun would get a hold of it and it would be a mess,” says Lepischak.

In April 1998 SOY launched with funding from the Trillium Foundation and those fears proved unfounded. Over the years programs such as the Pride Prom and the annual Fruit Loopz cabaret during the Pride Festival have become staple events for the underage set, in addition to literary group Pink Ink and spiritual group Essence. Lepischak attributes SOY’s success to its well-defined framework.

As the city’s population has changed so has SOY. In 2002 it extended the participant age to 29 to accommodate older youth and newcomers from many cultural backgrounds and added the after-school program Alphabet Soup for high-school age kids.

That same year organizers noticed a lot more black and immigrant/refugee youth coming to SOY, undertook antioppression training for staff and volunteers and started culturally focused groups such as Express for newcomer queers and Black Queer Youth (BQY) — which was until recently one of the only social groups for young black queers in Ontario and one of SOY’s best attended.

A BQY meeting will start with a meal, such as roti, curry chicken or pizza, followed by a guest or a discussion question: Is America ready for a black president? If you were to describe your feelings at this moment, what would they be? What do you think of the recent beatings in Jamaica?

“I try to keep them up on current events so that they can speak to the issues rather than guess,” says Lorelei King, BQY and community programs coordinator. “We try to follow guidelines. Everyone makes an effort to allow people to talk and speak directly to that question. We get involved. It’s quite loud at times but not in a bad way. It’s loud because people are passionate about what they’re talking about and there’s lots of laughter. And sometimes there’s the odd drama.

“It’s like talking to family, so it’s really important to maintain that space because there’s nothing else like it [in the city] to make the youth feel comfortable taking up space, which may not be something they’re used to doing.”

King likes to keep the group structured to train her youth facilitator. She eventually sees SOY becoming more youth-involved, with adults stepping back to advisory roles to allow the youth to take on more leadership.

***

Despite the modest, institutional surrounds at Sherbourne Health Centre (SHC) the hustle and bustle in the second-floor room where the drop-in meets feels more like a high school social club. On the wall a photographic timeline of SOY chronicles the work of participants and volunteers and highlights the organization’s move to its permanent home at Sherbourne in 2004.

Lepischak says the move gave SOY much-needed stability. The advisory committee knew Trillium’s funding wouldn’t last forever, but didn’t want the organization to become an independently run body, perennially reliant on fundraising.

“We weren’t the most attractive organization from a financial perspective,” she says, “and if you don’t have a good year from a fundraising perspective, you’re fairly vulnerable. “

SHC, which already had the LGBT Primary Health Care program and serves a similar demographic of immigrants and homeless people, offered to house SOY. The Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care also began funding half of SOY’s operating budget in 2006 to the tune of $170,000. The rest of the budget comes from fundraising and grants.

The combination of SOY and SHC’s LGBT Primary Health Care program played a role in Tyson Purdy-Smith’s decision to move to Toronto. The 20-year-old was visiting the city last summer hoping to find doctors specializing in female-to-male transitioning and discovered SOY’s Trans Fusion Crew, which he now attends regularly. It’s a far cry from his teenage years in Kananaskis Valley when he hitchhiked a two hour-plus journey to Calgary to attend a monthly trans support group.

“To find so much in this one little building was shocking,” he says. “People here could answer every question I had and they had been through everything before and could hook me up with doctors — not just doctors to who would prescribe hormones but a family doctor who is familiar, knowledgeable and respectful.”

“There’s a real feeling that SOY belongs to the community even though it’s part of Sherbourne,” says Lepischak, who now oversees all the queer services at Sherbourne, including SOY and the primary care program. “It’s astounding to see what happens to young people when they come here; to watch them grow and change in a way that’s not about ‘curing’ or treating them.”

At the Monday night drop-in the sense of ownership seems instilled in some of the attendees. Grant, for example, wants his peers at the drop-in to feel comfortable coming to him for advice, as he says his family already does for info on his grandfather’s personal care. “I’m attending every workshop I possibly can,” he says.

Linden, one of the vocal parties in The L-Word debate, is a University of Toronto student, has been interning at SOY since October. At 23 she’s able to slip from relatable confidante to sexual health expert and answers every question with a combination of unforgiving frankness and humour.

It takes a few minutes to get things started after collecting all the yellow sticky notes with the anonymous questions. Linden fiddles with the blown up condom in her hands as she attempts to gain the room’s attention. Once the room has quieted down, she begins an instructional preamble that’s as funny as it is loud.

“SOY does not encourage orgies for liability reasons. But if you want to plan an orgy, please do so on your own time,” she booms. The room erupts in laughter. “And do not snicker at questions you think are stupid.”

Questions include: Do condoms reduce intimacy? Is it true vegetarians taste better? Is it safer to use two condoms at once? Is it dangerous to insert food into your ass? And is bad to have too much anal sex? The answer to that last question: It can be, but if you know your own limits, you have a lot of lube and you’re relaxed, it’s probably cool. Lexi immediately dismisses reports of studies that attribute loose bowel movements in 80-year-olds to excessive backdoor action as “unproven.”

The drop-in is currently operating with temporary coordinators. Both of the previous coordinators left within one week, leaving SOY to scramble to find replacements. The kids are not happy. The previous coordinators were both in their 20s and well liked. By contrast, Krin Zook, the temporary coordinator is 54 and has had a long day. Though she’s deeply committed to SOY, as a mentor and the coordinator of Essence, she retreats to the kitchen to tidy up during the sex talk.

“I’m not going to be someone they trust right away,” she says. “I don’t have their energy — that’s why Essence is going for me because it’s a lot of meditation. This is more high energy.”

Linden, on the other hand, seems ideally suited to the job. Though she says she’s too young to step into a coordinator role, she can’t see herself walking away from SOY when her internship ends in June.

“I don’t see myself being able to separate,” she says. “The Monday night drop-in has been really important to me and I’ve had so many good experiences that I want to continue with it. At my age we’re all struggling to find our place in the world and the youth can relate to that.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra