Canadian researchers say that mutated strains of HIV in Saskatchewan are causing faster-developing AIDS-related illnesses in people with the virus.

The results from a new study were presented during the 2018 International AIDS Conference in Amsterdam July 26, 2018.

Researchers say that while HIV usually takes years to progress into AIDS-related illness, some cases in Saskatchewan, especially among Indigenous people, are leaping from infection to illness in only a few months.

The rapidly progressing cases are caused by immune-resistant HIV, strains of the virus that have evolved to quickly evade and defeat the human immune system.

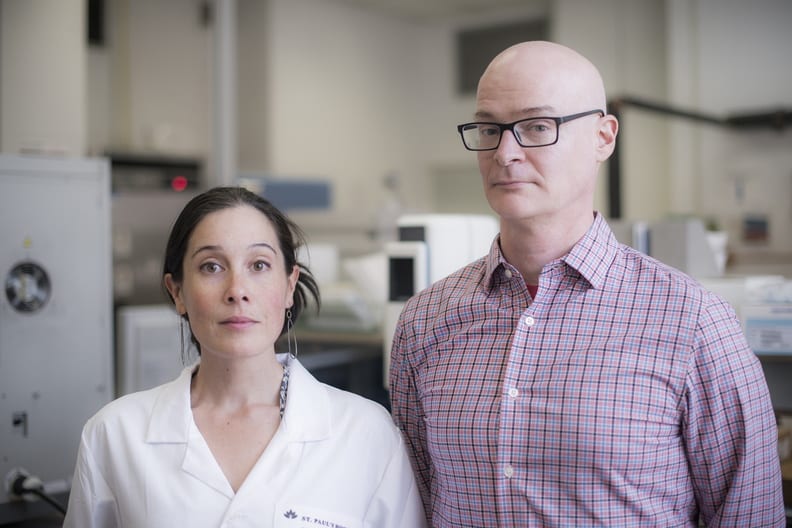

But what is immune-resistant HIV, and what does it mean for people living with, treating, studying or trying to protect themselves from the virus? Xtra sat down with Jeffrey Joy, a research scientist at the BC Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS and Zabrina Brumme, an associate professor of health sciences at Simon Fraser University, to understand the science behind the story.

What is mutated immune-resistant HIV?

While the human body can’t entirely fend off HIV infection, it can put up a good fight. The human immune system slows down new HIV infections, often preventing sickness for a matter of years before the virus finally gets the upper hand if left untreated.

Unfortunately, the HIV virus mutates extremely rapidly — faster than nearly any other virus that infects humans. In some cases, HIV mutates in a way that allows it to evade the host’s immune system, and a virus that dodges the immune system will make the host sicker more quickly.

Since humans have a wide diversity of immune genes, specific mutations in the virus target people with specific genes. That means if a virus mutates to evade your immune system, it will also more likely evade the immune system of someone genetically similar to you. In Saskatchewan, where HIV disproportionately affects Indigenous people, some strains of the virus have adapted to immune genes that are more common in the Indigenous population.

“What’s happening in Saskatchewan is that people are getting sick with a virus that’s already adapted to them, and so there’s not even a fight,” Brumme explains. “They just get sick really fast. The virus has already won before it even infects someone.”

Why is this happening in Saskatchewan?

Immune-resistant strains of HIV appear all over the world, Joy and Brumme say, but there are two factors that make the phenomenon more likely: an out-of-control HIV epidemic and relatively high genetic similarity in a population.

According to the new study, immune-resistant strains have appeared, for example, in Japan, where immune genes are relatively similar, and in Botswana, where the virus infects nearly a quarter of the adult population.

Saskatchewan suffers from both factors. Rates of HIV infection in Saskatchewan are the highest in Canada, more than twice the national average and even higher in some concentrated regions. At the same time, 80 percent of people living with HIV in Saskatchewan are Indigenous, and share many of the same immune genes.

As a result, Saskatchewan has startling rates of immune resistance. Joy and Brumme found at least one immune-resistant gene in 98 percent of the HIV samples they examined.

“Saskatchewan has the perfect storm of factors that allow this to happen very rapidly, and that’s why we’ve seen what we’ve seen over the past few years,” Brumme says.

Does immune-resistant HIV only affect Indigenous people?

Immune-resistant HIV in Saskatchewan is more likely to affect Indigenous people, Joy and Brumme say, but it can affect other people as well. People with similar genetic backgrounds tend to share similar immune genes, but the correlation is far from perfect.

For example, one common gene, called B-51, that is targeted by some strains of immune-resistant HIV is present in 30 percent of Indigenous people but also in 10 percent of people with European ancestry.

Immune-resistance appears in HIV everywhere, and can affect anyone. The rapid circulation of HIV among Indigenous communities in Saskatchewan has led to strains of resistant HIV that are particularly dangerous to Indigenous people.

Are immune-resistant strains of HIV also drug resistant?

“The good news is that if we get people on treatment right away, they’re going to have a very good outcome in the long term,” Joy says.

While some strains of HIV can become resistant to certain drugs, that’s not what’s going on in Saskatchewan. Immune-resistant strains of HIV are just as treatable as any other strain, and people on treatment can live healthy lives with almost no chance of passing on the virus to anyone else.

Immune-resistant strains of HIV are also no more infectious than other strains, and are just as easily stopped by pre-exposure prophylaxis drugs — medication taken by people who do not have HIV in order to prevent infection. The sole difference that makes immune-resistant strains of HIV dangerous is their ability to evade vulnerable host’s immune systems and cause illness more quickly.

What can we do about it?

The solution to immune-resistant HIV in Saskatchewan is simple, Joy and Brumme say, but the execution remains difficult. If people carrying immune-resistant strains of HIV are identified and given treatment they will not only be healthier themselves, the spread of the those strains will also stop.

Testing, treatment and prevention, Joy and Brumme say, could halt the epidemic.

At the same time, the researchers say, HIV in Saskatchewan is entangled with a host of social factors — colonialism, poverty, lack of access to medical care, mental health problems and drug use. Unlike in BC or Ontario, where HIV is most commonly spread through sex, injection drug use is the primary vector for HIV in Saskatchewan.

Joy and Brumme say the province will need more than just drugs to halt HIV; it will need social support, community engagement, harm reduction programs and more access to all kinds of medical care.

Joy points to Saskatchewan’s new budget commitment of $600,000 this year for HIV medication, including coverage of HIV prevention medication, as a good sign. HIV advocates in Saskatchewan, however, say federal contributions to fighting the epidemic are still lagging behind.

“What needs to be done is obvious,” Brumme says. “But it’s the very long history and complexity of social inequities combined with populations that are difficult to reach. Practically it’s a little bit challenging, but it’s very clear what needs to be done.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra