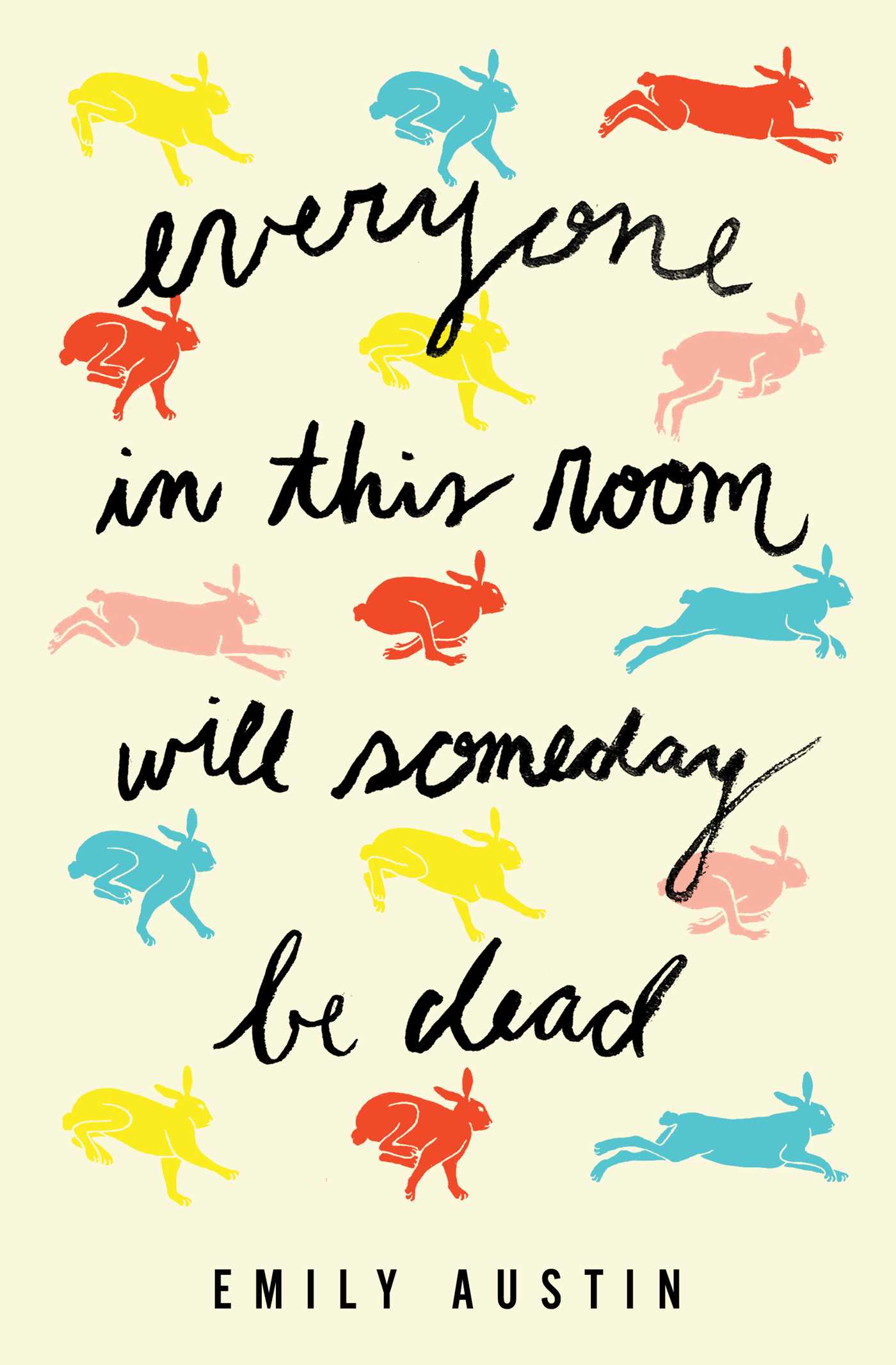

Emily Austin’s debut novel Everyone in The Room Will Someday Be Dead is, unsurprisingly, about death.

The death of a childhood rabbit. The fear of a loved one dying. Death in the news. The death of a local church’s beloved secretary.

Austin’s protagonist Gilda is obsessed with death to the point of anxiety. A regular self-check-in at the local ER for repeated panic attacks, Gilda can barely keep a grasp on her relationship with her girlfriend. But when an attempt to respond to a local ad for therapy leads to the atheist lesbian accepting a dead woman’s job at a local Catholic church, Gilda’s obsession with death is thrown into the spotlight.

I read Everyone in This Room Will Someday Be Dead in the midst of a record-shattering heat wave here on the west coast of Canada. The muggy air around me only added to the intentional anxiety of Austin’s rapid-fire, disjointed prose as Gilda navigated a real relationship, a fake relationship with a self-help guru, hiding her homosexuality from the church and grappling with whether life means anything at all.

It was an immersive experience, and a scintillating debut novel for the queer Canadian author. The interplay between queerness and mental health is a rich palette for painting a narrative, and through Gilda’s eyes, Austin lets us all feel the push and pull of what we know and what we think we know about ourselves and the world around us.

I sat down with Austin to talk about queer library books, religion and writing the queer fiction you wish to see in the world.

To start, could you give me a bit of background on what inspired you to write about anxiety, queerness and religion in this way?

I was at a funeral around the time that I wrote this book. I grew up Catholic, but there was a long delay between the time I had been in a Catholic church and at this funeral. I was looking around and feeling like I was seeing that space with fresh eyes for the first time, and realizing what strange spaces Catholic churches are.

I think that’s where I first started thinking of Gilda as a character. But then, besides that, I was trying to think of things in my life that I would say have been difficult, and to use those like a jumping-off point. Because when you write something, you’re kind of forced to think about that topic a lot, and I think that having to focus on certain things that have been difficult, like mental health, for example, is a tricky way of me doing some self improvement. I was always thinking of two things [religion and mental health] that I felt like, if I thought about them a lot, I might be able to resolve some issues in a personal way by writing about them.

I found it so interesting how the prose itself kind of made me anxious. I was telling my partner about the book, and I described it as “making me feel bad” but also that it felt intentional. So I’m curious about how you worked to create that anxiety in the writing itself.

One thing that I was trying to do with that focus was to help people who don’t feel anxious have an understanding of what it’s like. (Though the byproduct of that is probably triggering for people who are anxious.) I was consciously trying to think of how I could explain what anxiety feels like to someone without just saying, you know, “Your heart rate is going fast.” So I was trying to put people who aren’t anxious in the shoes of someone who is anxious. That’s why I tried to write choppy in some spaces and jumping from one thought to another and things like that.

Gilda is queer and you’re queer and I’m queer and the book is queer—we’re all queer here. But in the book, Gilda’s queerness is not the only thing about her. It does inform the narrative, but it still felt like a very kind of realistic portrayal of being a queer person and dating as a queer person and all that. Can you talk a bit about queerness in the book?

So I went to school to be a librarian. And when you study being a librarian you take reference classes and learn how to research. We also took a collection-development class, and in that class I had a project; the project was to pick a subject and a sample of libraries across Canada and see how well their collections represented that subject.

I picked LGBTQI+ fiction: I looked at stats for how many people identify as queer in Canada and I also looked at things like hate crimes committed against queer people and how many people identify as queer in general. I came up with the numbers, and I came up with a percentage that libraries should have of fiction and then I took a sampling of some libraries. I assessed how well their collections represented that material. None of them did well.

The next part of the assignment was to propose what books should be used to fill the gaps. To identify what those books should be, I looked at the same criteria used to recommend any books—what are the reviews of the book, has it received any awards—then I found queer-specific criteria for books. That included things like, if there’s a romantic relationship neither partner should die and also that the story shouldn’t be just about coming out, for example. So there was a whole list of criteria and by using that criteria, I tried to find books that would fill the gap. But I couldn’t; like, there weren’t any, they didn’t exist.

That was eight years ago, and I know a lot of great queer books have come out since then, but I had that in my mind. I remember specifically looking at lesbian fiction and seeing that it was especially really poorly represented. There weren’t very good options that met the criteria of what good quality fiction is in general, but also that doesn’t have someone die. I had that in mind while I was writing this book, that I was trying to fill that gap. But I was also trying to write about what the experience of being depressed and queer is like.

Yeah, I think the experience of being depressed and queer is a familiar one and I think the interplay between queerness and either anxiety or depression is something a lot of queer folks experience. And so it’s nice to see it kind of portrayed in that way.

Speaking of relationships between queerness and things—you were talking about being Catholic. A big thing in this book is how Gilda is afraid of being discovered as a secret lesbian working at this church. How do you see the relationship between queerness and the church?

I’ve seen a couple reviews of the book where I could tell the person might’ve been religious and they were reading it to see if the book was critical of Catholicism. Most people don’t seem to have been offended by it. I don’t think that the book is very critical of Catholicism, but on a personal level I’m definitely liable to write a book that is.

I do have a complicated relationship with Catholicism: I was raised Catholic and my grandma was very Catholic. She’s a very nice person and I have some nostalgia for some Catholic things. But that said, you know, Catholicism is incredibly anti-woman and anti-queer—particularly in Canada, and especially when I think about the Catholic school boards. I think of that and I think of the impact that had on me and on a lot of my close friends growing up and their careers as well. There’s a way real damage comes from a lot of Catholic ideology around queerness and around women.

What writers influence you in your kind of craft?

One of the first books I read that I really felt seen in was Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar. I remember the first time I read that book, I realized that parts of myself that I thought were personality traits were actually symptoms of mental illness. I think, especially in relation to how this book focuses heavily on mental health, that heavily influenced me.

This is your first novel. What advice do you have for folks who might want to be writing their first book?

I think for queer writers, one thing that I’ve been thinking about recently is to not write for straight people. Like, think of your audience as being entirely queer. I feel like that’s where you’re less likely to write something that is just about being queer, and more likely to write something that will really fill the gaps of what we’re missing.

For writers in general, I would say, “Just write.” I found before writing this book that I’m really hard on myself and always like to read everything I write and compare it to something else. With this book, I tried really hard not to do that as much.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra