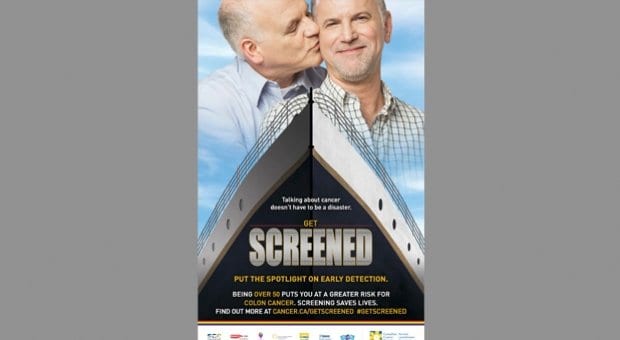

Inspired by top Hollywood movies, Get Screened campaign posters include a grey-haired man kissing his male partner behind a picture of the Titanic. Credit: Get Screened

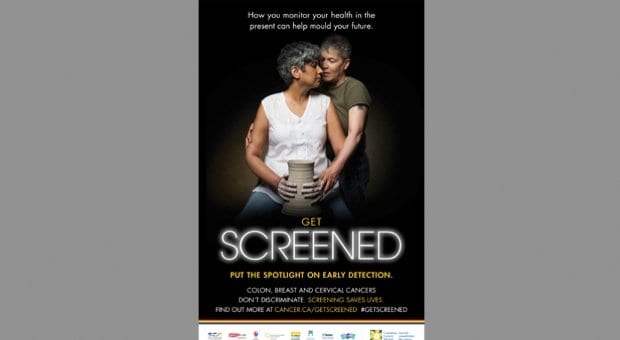

Inspired by top Hollywood movies, Get Screened campaign posters include a new take on Ghost. Credit: Get Screened

One of the great things about being a lesbian is you can never get cervical cancer.

Wait, what? While health myths aren’t uncommon, what’s troubling is that even healthcare providers have repeated that myth to their lesbian patients in the mistaken belief they were imparting factual health information.

Get Screened, a Canadian Cancer Society public awareness campaign, aims to address the barriers and myths that stand in the way of queer people getting screened for colon, breast and cervical cancers.

“LGBTQ community members are less likely to get screened, often because of barriers that exist at the healthcare system level, a misunderstanding of the needs of LGBTQ people when it comes to cancer screening,” says Kevin Linn, the Ottawa coordinator of Screening Saves Lives. “There’s often a myth out there that people who identify as lesbian are not at risk for cervical cancer. We’ve heard from people who have said their healthcare providers actually said that to them.”

Get Screened is the LGBT branch of the Screening Saves Lives campaign, which has been used in First Nations communities on Manitoulin Island and South Asian communities in the Peel region of Toronto, Linn says.

The peer-to-peer model, considered the best practice in promoting cancer screening, recruits community volunteers to act as health ambassadors to talk to their fellow community members about why cancer screening is important and to support them through the screening process, he says.

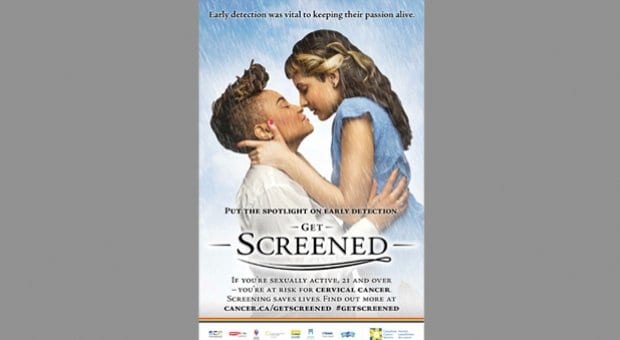

Inspired by top Hollywood movies, Get Screened campaign posters include a lesbian couple embracing in the rain à la The Notebook and a grey-haired man kissing his male partner behind a picture of the Titanic. The copy reads “Talking about cancer doesn’t have to be a disaster.”

Far from being a disaster, the campaign aims for relaxed conversations that can take place anywhere. From Oct 17 to 20, Get Screened representatives will be at the Inside Out LGBT Film Festival at the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa. Previous community outreach has taken place at Toronto Pride, Capital Pride and London Pride.

“I think a lot of the health promotion completed to date has been around STIs, and this is kind of the first time that cancer is being discussed within the community,” Linn says.

Key in the campaign’s success is the recruitment of health ambassadors. While peer support is hardly new to queer communities, Linn says the word “volunteer” sometimes brings up unwelcome and inaccurate ideas of what being a health ambassador would entail. He wants people to know they won’t be expected to put in long hours or have a staffer call up asking them to drive all over the city to volunteer.

Instead, after an initial eight-hour training day, health ambassadors will reach out to their own social networks on their own schedule.

“The conversations are meant to be had in natural settings, whether it’s having coffee with a friend or at a dinner party and really making it not so scary, the whole cancer screening process,” Linn says.

As Get Screened reaches out to queer community members in Toronto, Ottawa and Hamilton, many barriers have been identified. Cervical cancer screening, which is carried out during a pap test after age 21, often takes place as female patients are getting birth control. For queer women who don’t need birth control, this is often a missed opportunity to discuss cervical cancer screening with their healthcare providers, Linn says.

“There’s also not clear guidelines for cancer screening within trans communities, so that’s also one thing we’re working on,” he says. “To participate in the Ontario breast cancer screening program you must have an ‘F’ on the healthcare card. If someone has changed the ‘F’ to an ‘M’ on their healthcare card but still has breasts or breast tissue, they’re not able to participate in the Ontario breast cancer screening program.”

It’s important to address barriers at the individual, community and healthcare-system level, Linn says.

“A lot of the barriers that are facing LGBTQ community members are not documented,” he says. “They haven’t been published, they haven’t been researched, but we do know that they exist because some stats have shown that there’s actually lower rates of cancer screening when it comes to LGBTQ community members.”

What is known is that early detection saves lives, so increasing cancer screening in the queer community is crucial, Linn says.

“Colon, breast and cervical cancers will account for more than 43,000 new cancer cases every year and more than 9,000 deaths in Canada. They’re among the most easily diagnosed cancers,” he says. “Colon cancer is one of the largest causes of cancer deaths, yet it is 90-percent treatable when detected early.”

For more information.

To become a health ambassador, contact Linn directly by email at klinn@ontario.cancer.ca.

If you live in Toronto or Hamilton, email Arti Mehta at amehta@ontario.cancer.ca.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra