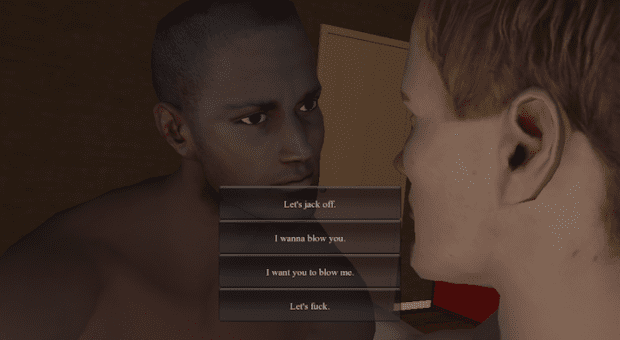

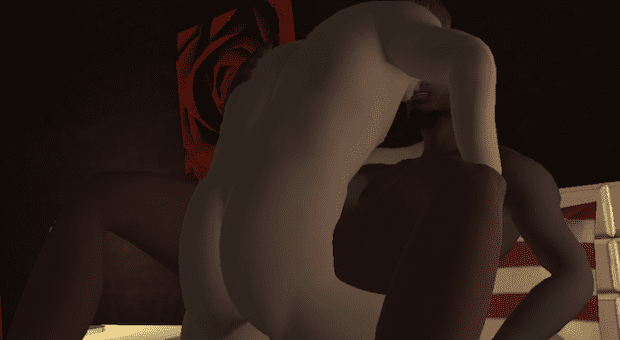

For what is essentially an interactive public service announcement, SOLVE-It is surprisingly hot and explicit. Credit: Screen shot

For what is essentially an interactive public service announcement, SOLVE-It is surprisingly hot and explicit. Credit: Screen shot

Everyone else has left the party and it’s just you and Steve making out in his mood-lit bedroom. Up close, he looks a touch pixelated and zombie-eyed, but he’s buff and into you, so you decide to have unprotected sex with him anyway.

“Hold up. Anal sex without a condom?” asks a future version of you. He’s been monitoring you all evening, interrupting at the most inopportune moments. “You know how dangerous that is. Whether you’re a top or a bottom, protection keeps you safe from most STDs, including HIV, the virus that causes AIDS. You don’t want that worry.”

You decide to ignore “future you.” You two will have a chat about HIV later, but for now you spread your legs and let Steve fuck you bareback.

This is level one of Socially Optimized Learning in Virtual Environments, or SOLVE-It, a game designed by Lynn Miller of the University of Southern California and colleagues to promote safe sex.

For what is essentially an interactive public service announcement, SOLVE-It is surprisingly hot and explicit, and according to John Christensen, a member of Miller’s team and assistant professor at the University of Connecticut, it is the cutting edge of HIV prevention research. It was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health and the American Psychological Association.

Previous studies have shown that shame is associated with self-harming behaviour, so SOLVE-It was specifically designed to be gay-positive, sex-positive and generally ego-boosting.

It seems to work. In a study of 921 self-identified HIV-negative men aged 18 to 24, those who played the game reported on average reduced feelings of shame. As the researchers predicted, participants who exhibited reduced shame were less likely to report having unprotected anal sex in the three months following the game.

Not all participants had the intended response — some even had increased shame after playing — but the results are promising enough to establish the potential of these kinds of interventions.

In addition to targeting shame, the team designed SOLVE-It to turn players on — though, for the record, Christensen prefers to call it “sexually arousing” rather than “pornographic.”

“There’s this idea called ‘state-dependent learning,’” Christensen explains. “If you are learning information in a certain context, it’s actually easier to recall that information later down the road if you’re in a similar context.”

So if you learn how to navigate a sexually charged situation while aroused (as opposed to, say, while seated in your eighth-grade classroom), you might find it easier to recall that information the next time you’re aroused.

At this point, SOLVE-It is a promising prototype, not a fully developed game. There are only a handful of storylines, and due to budget constraints, only three ethnicities are represented. In fact, all the characters have identical bodies and faces, differing only in their outfits and colouring. Given these limitations, it’s not surprising the game hasn’t worked for everyone. Not all players will find the scenarios hot or realistic or feel confident mingling with a uniformly muscular, able-bodied cast that looks nothing like them.

But SOLVE-It’s creators plan to further develop the game, creating more options and integrating feedback from the community as they go. Christensen hopes to keep pace with the latest in gaming technology.

“I personally have an interest in highly immersive virtual reality,” he says, noting that the cost of this technology is dropping sharply. “I would like to . . . move to three dimensions, where you can turn around in 360 degrees and actually walk ahead and bend over . . . That kind of immersion can only, in my opinion, increase the effectiveness of these interventions.”

Indeed, if these games evolve to the point Christensen is imagining, we won’t need safe-sex interventions at all. We’ll just do it with Steve.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra