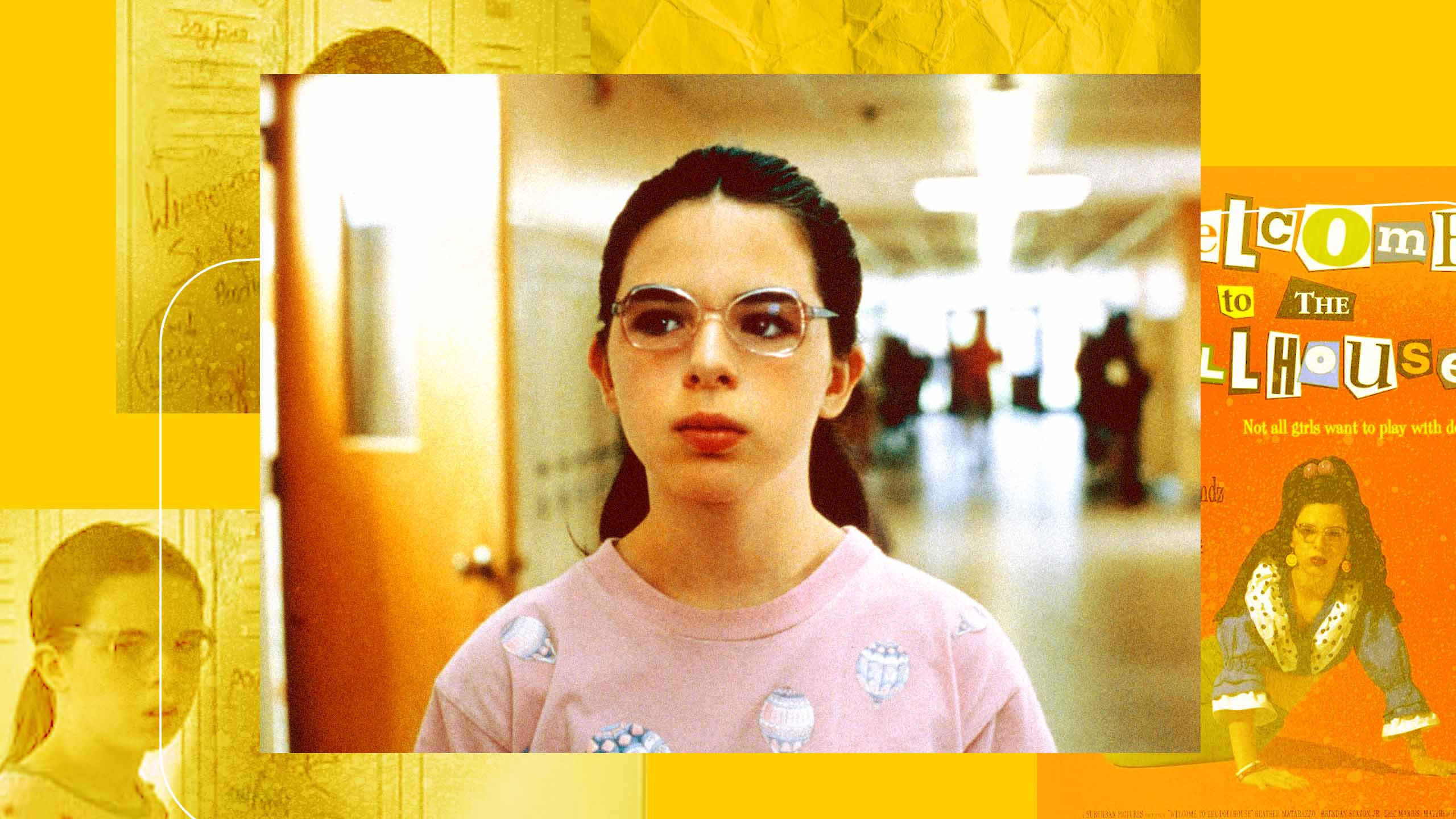

I first stumbled upon Todd Solondz’s 1995 film, Welcome To The Dollhouse, when it arrived at my suburban video store, and was absolutely flummoxed by its cover: a Pee-wee’s Playhouse-style faux-retro housewife, slumped on the floor of a ketchup-red abyss, dead-eyed yet somehow coquettish, staring directly at me beneath a violent ransom note proclaiming its title.

Who was this girl? Had I seen her earlier that summer in the gently necrophilic live-action remake of Casper, after which my deeply Catholic mother had taken me to Swiss Chalet for a conversation contextualizing the occult and explaining why I should never, ever touch a Ouija board? Or the year before in Monkey Trouble, in which a troubled child forms a Bonnie-and-Clyde-style alliance with a capuchin monkey? No, those were different Hollywood outcasts. I’d never seen Heather Matarazzo, Dollhouse’s befuddling cover girl, in anything else.

But I recognized something about her. Something queer.

If you’re not familiar with Dollhouse, it charts a week or so in the life of 12-year-old Dawn Weiner (Matarazzo), known to most of her junior high as Weiner Dog. Some people are born under a bad sign; Dawn seems to have been born into the wrong story. She’s ignored but somehow still a target, a black sheep middle child stuck between a rock (older brother Mark, an overachieving computer nerd) and a hard place (tutu-clad saccharine-sweet kid sister, Missy). Dawn lumbers under the weight of a New Jersey suburban ennui to which those around her seem immune. Her family laughs at the same jokes for the same reasons while she hides in her room, kneeling in front of a cardboard shrine, invoking hunky crush Steve Rodgers (Ugly Betty’s Eric Mabius) to rescue her from a split-level shag carpet nightmare.

But Dawn’s wishes never come true, and her good intentions only seem to make things worse. She’s labelled a cheater when others copy answers from her test, and nearly blinds a teacher when defending herself from her classmates’ spitballs. In an excruciatingly familiar early scene, Dawn comes to the defence of another junior high untouchable who runs from her aid, preferring physical abuse to social suicide.

When I first watched the film, I sympathized with Dawn because, no matter how many times she gets knocked down—often literally—she gets back up. Dawn, I thought, was a victim, like me, and that made her good.

But to maintain this image of her I had to ignore all of the bad things Dawn did, like hold a hammer over the head of her sleeping sister and wonder if it would split like a watermelon or crack like an egg.

Being bullied is a slow-drip nightmare—I once returned to my briefly unattended science textbook to find that a classmate had used a Sharpie to scrawl “I hate your sweaters” across its laminated cover—but oppression does not make us pure. Dawn and I still had plenty of metaphorical dirt on our hands: we could be petty, manipulative, horny, hungry, lazy, jealous and casually violent. We leveraged the same social structures that punished us to punish others, because, for the bullied, the elusive rush of superiority can be extremely satisfying (when I found myself the third wheel of an eighth-grade friendship triangle, I tried—and failed—to start a rumour that the pair was gay). We were simultaneously infuriated with and fascinated by our bodies, which we fetishized, ignored and abused while they silently laboured to keep us alive.

Neither Dawn nor I were unwaveringly good. Sometimes we were monsters. And now, on the other side of a solid stretch of psychotherapy, I’m inspired by her monstrous side. Because, beneath all of our moralizing, life is queer. And that’s funny.

Barely 10 minutes into my first viewing of Dollhouse, I realized what it was about its box art that had caught my attention. Everything about that photo of Dawn, slumped on the floor like the world’s most disillusioned cover girl, made sense to me, because we both lived in a senseless world. Our kindness was rewarded with contempt, our favourite things were liked by us and us alone and the thing we hungered for most from the depths of our elastic-waisted jeans was non-negotiably forbidden. Dollhouse helped me understand that straight suburbia was a hell you found in the “”comedy” section. Dawn was a kindred spirit, and with every viewing—I watched the film twice more that first weekend and continued to rent it on a regular basis—I felt a little less alone, a little less condemned and a little more in on the joke of my queer existence. The sad fact that the wide receiver of the Catholic Central Saints would never take me to prom wasn’t sad at all: it was delightfully absurd. Dollhouse allowed me to see my life through the lens of another, more accommodating genre.

As I worked to understand who I was, Dollhouse became a secret handshake, and inviting friends to a viewing was a sign of trust. Watching Dawn’s blood boil as she was pushed deeper into her own private hell was undeniably cathartic, but sharing her suffering with others was an even greater release. Regardless of our sexualities—my crew was mainly composed of straight Italian girls who liked boy bands and Brio—we could all relate to Dawn Weiner. None of us were popular. A college writing teacher told me that laughter is recognition, and Dollhouse was the funniest thing I’d ever seen.

But with every viewing, Dawn’s world stayed the same, and mine did, too. The boys I lusted over became men, while I stayed short and smooth, a pudgy face framed by a slack bowl of styleless and disconcertingly shiny hair. Out for dinner, I’d wait as servers took my family’s order and, finally turning to me, would inevitably chirp, “And what can I get for the little girl?”

I eventually realized that some of my growing pains weren’t going to end—but I had no idea that the girl behind Weiner Dog, actress Heather Matarazzo, could also relate.

“I was 11 years old when I did Dollhouse,” Matarazzo told me when I spoke to her nearly 30 years later for my podcast, You Made Me Queer!. “It was the summer of 1994 and it was the first time that I had met out queer people. It was the first time that I had met gay men and women.”

An important discovery because, like me, Matarazzo had felt different, too.

“I describe it as like when Helen Keller discovers her first word with Annie Sullivan. Like, ‘It has a name, Helen. It has a name.’

“And I’m like, ‘Lesbian.’”

Matarazzo was raised in a Catholic household (another thing we had in common), so she kept this new word—“lesbian”—to herself. But knowing it helped her to imagine a future where she might not be alone. Where a capital-G God would intervene in a nihilistic world and give the meek—and the queer—their goddamn due.

“I had a very complicated relationship with God,” she said, recalling how she would often pray that the dysfunction in her family’s household would end. When that didn’t work, she assumed it to be a sign that she was undeserving of divine intervention.

“It was my fault. And then somewhere in there was the ‘well, maybe it’s because I like girls.’”

Hymnal drop.

Finding out that Matarazzo had also been tricked by goodness™, just like me and Dawn, was immensely freeing. It was also deeply understandable, because goodness™ is the ultimate goal of the suburban experiment: an orchestrated performance of assimilation in which points are awarded to for the best impression of a “satisfied human being”™ (everything is trademarked in the suburbs).

That’s why the conformity demanded by suburbia will always be at odds with the queer experience. Because to find queer joy, we have to stop trying to be good.

We have to unmuzzle the monster.

Ever since we first locked eyes through the cover photo of that video store VHS, Matarazzo has felt like a friend, and I’d wondered if speaking to her would be a mistake. Popular wisdom counsels against meeting our heroes because they’ll shatter our fantasy. But I liked Matarazzo right away; yes, she’s smart, kind and compassionate, and every bit as funny as her performance in Dollhouse might suggest (as a side note, she also has gorgeous hair), but I was delighted to discover that she herself isn’t especially good. At one point in our conversation, she suggested that I might prepare for the apocalypse by learning to hot-wire both a boat and a car (“It’s all just wires”). Enchanted, I assured her I would.

Queer folks are told “it gets better,” but how can things get better in a senseless world? Things don’t always change—and that’s why Dollhouse is a comedy.

In the film’s final scene, Dawn sits aboard a bus to Disneyland (a bus! From New Jersey to Florida!) with her school’s choir, the Hummingbirds of Benjamin Franklin Junior High. They sing an inane fight song to pass the time and Dawn whispers along as if possessed, her lips moving in sync with those around her but with eyes seemingly fixed on an alternative destination.

Hooray! hoorah! Sis-boom-bah!

Now put on a smile, kids, wipe off that frown!

The camera zooms in toward Dawn, strapped in amongst a bus full of carefree girls, her expression stern and resolute. She’s not simply waiting for the movie to end. I imagine that, after all she’s been through, she finally understands that living in turmoil doesn’t mean surrendering to grief. It looks like she’s finally found the way out.

For some folks, “sense” hinges on the existence of an inherited world of cause and effect—where a childhood rich with agonizing exclusion, unrequited love and dark trauma is punitive, a just consequence that could have been avoided if only we’d been good and behaved.

But queer folks know that sometimes, no matter what you do, the joke’s on you. And once we understand that, we’re free to laugh.

Three decades after that first rental, I keep returning to Dollhouse. With every new viewing, I take comfort in the hilarious paradox that life gets better because, in a lot of ways, it doesn’t. So much of what happens to us doesn’t add up. But Weiner Dog, Matarazzo and me—and so many others—were born into a chaos that only determined the first part of our stories. In the monstrous second acts of our lives, we can be queer without apology and transform our worlds into dark comedies of our own design.

In other words, we may not choose the setup, but we get to choose the punchline. And that’s the part that sticks.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra