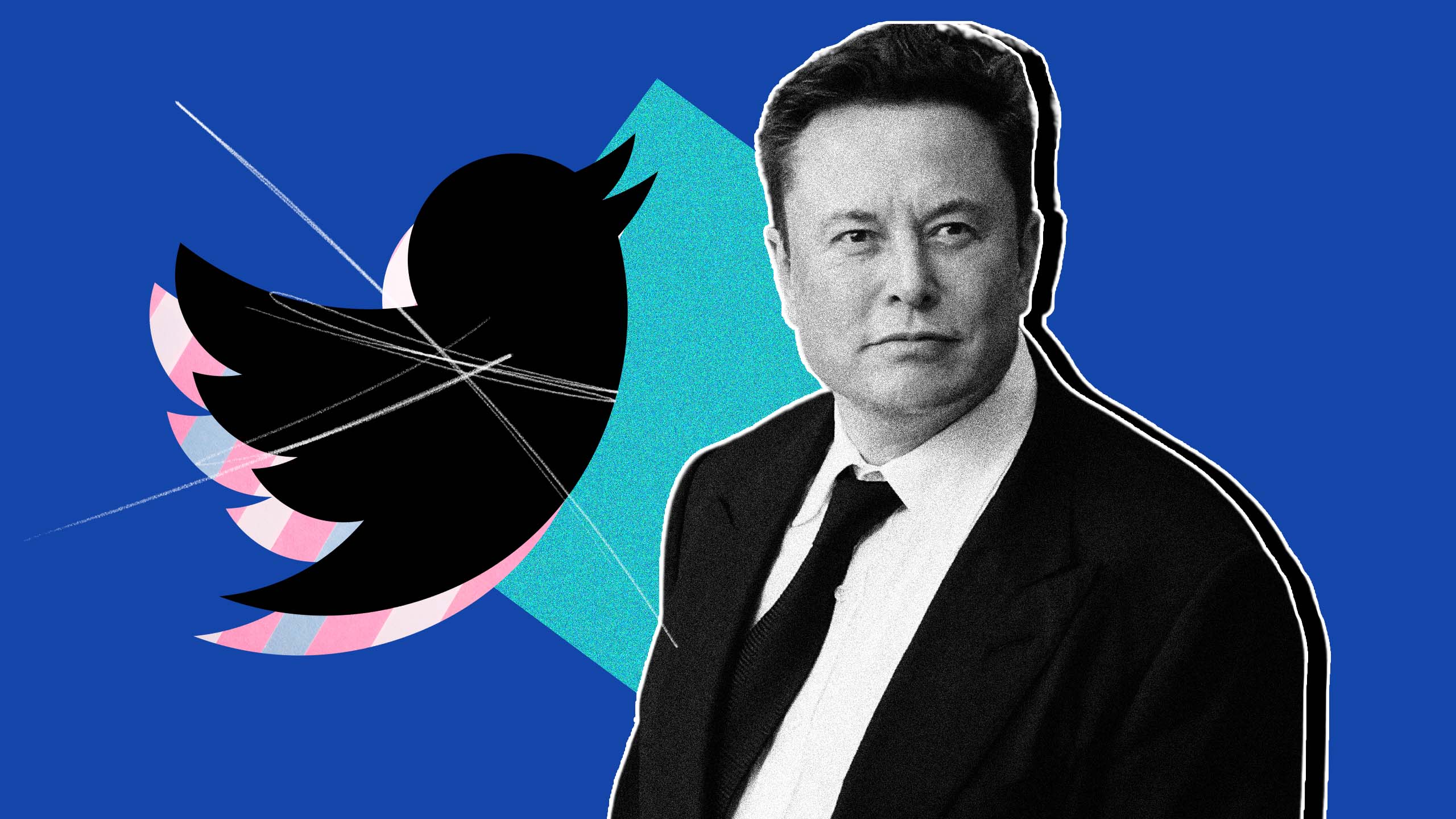

Thousands of shitty white straight guys have tried to bully me off Twitter in the past decade and a half, but, in the end, it may take the shittiest and whitest of all straight guys to succeed: Elon Musk, South African billionaire and celebrity transphobe, took control of the site after a USD $44 billion offer last month, and is currently burning it to the ground.

Queer and trans people are fleeing the site in droves, and it’s not hard to see why: Musk’s right-wing sympathies are no secret. He’s been complaining about trans people’s pronouns (an “esthetic nightmare”) for ages, while also blaming “communism” for the fact that his trans daughter doesn’t speak to him. Reportedly, one of his first priorities for revamping the site was to gut the rules against misgendering and deadnaming trans people. Twitter’s underbelly of bigots and trolls, never quiet even on its best days, has been emboldened by the Musk regime.

Social media platforms age out of relevance all the time, and Twitter lasted longer than most. It was arguably overdue for a replacement. Yet the trans people I’ve spoken to about the Musk takeover aren’t just moving on. We are grieving the loss of a community—problematic, far-flung and virtual, but real—that feels as if it’s being taken away.

“Twitter has always been a harassment machine,” says digital sociologist Katherine Cross.

Any responsible eulogy of Twitter must begin with the acknowledgment that Twitter has always sucked, particularly for marginalized people. The site’s harassment problem was so bad that there’s an Amnesty International report about it. Neo-Nazis and white supremacists built devoted followings through the platform; right-wing culture war campaigns like Gamergate flourished there. Twitter’s most toxic bully became the president of the United States, then used his account to launch a coup.

According to Cross, this was not just facilitated, but encouraged, by the site’s design. She’s written and spoken extensively about how the very structure of Twitter—its reliance on “engagement,” no matter how toxic—guarantees mobbing and abuse.

“It’s a wide-open, everyone-to-everyone platform that affords you the illusion of shouting into the void even as you may be yelling at a specific person,” Cross said in an email interview with Xtra. “It’s extraordinarily easy to put a tweet in front of a hostile audience [through quote-retweeting] and it’s extraordinarily easy to gin up the critical mass required to dogpile someone with tons of harassment in a thread that stretches infinitely from one of their tweets.”

“Gender-critical” transphobes, in particular, became infamous for using the site to dox, threaten and harass trans people, often with little or no help from the content moderation team. Ela, a 31-year-old writer of queer-affirming fiction from Belgium, says that transphobic abuse came her way “all the time”—“from ‘you deserve to die’ and [‘kill yourself’] in my inbox to accusations of pedophilia and grooming below tweets”—and that over time, the risks of being visible outweighed the benefits. (Ela’s last name, like that of several others interviewed for this article, has been withheld to prevent harassment.)

“[Having] a post gain traction also meant that the GC’s and the transphobes flocked to the post to start shit,” she said by email. “At no point did Twitter suspend anything I reported unless I wasn’t the only one.”

Again, Twitter’s status as a petri dish for online transphobia had real-world impacts. Twitter is, notoriously, a go-to platform for journalists and other pundits and, over time, its inflated and vitriolic trans “debate” began to leak into mainstream media.

“I believe Twitter is significantly responsible for the current anti-trans backlash,” Cross says. “NYT columnist Pamela Paul’s view of trans people is incredibly Twitter-brained, dramatically overemphasizing and overstating discourses that have little to no currency except in certain pockets of Twitter she’s become obsessed with. To look at J.K. Rowling’s latest book, meanwhile, is to see a profound and almost pathetic obsession with the platform. And Jesse Singal? Has there ever been a man who is More Online?”

Reader, there has not been—except for Elon Musk, who now owns the joint. So why is this news so upsetting? Why were so many trans people stuck on Twitter, long after the platform’s problems became apparent, and why would anyone be sad to see it go?

“I’m a person who makes a lot of things,” says Aidan, an artist and craftsperson on the West Coast of the U.S. Queer erotica is one thing Aidan makes; there are also paintings and costumes. And then there’s this: “I also am a, um … well, I make sex toys. I make silicone dildos, and that is extremely limited in where I can sell and discuss them.”

When we talk about trans “community” on Twitter, it’s easy to reduce it to what we unlovingly call “the discourse”—the endless stream of maddening argument and half-baked queer theory that arises out of several thousand trans people all trying to make conversation at once. Yet for many, Twitter is also their means to find real-world practical support. Trans people are famously poor and underemployed. Being able to market to each other directly over the internet has made it possible for many trans people to sustain themselves, and even to establish an informal economy just to the side of the cis mainstream.

For someone like Aidan, no social platform can really replace Twitter. Tumblr, for example, has a series of ever-shifting rules about adult content, and Aidan’s posts often get unceremoniously taken down by the moderation algorithm: “It’s just impossible to run a business when you never know if your stuff is going to be there five minutes after you post it. Whereas with Twitter, I have not had that problem.” At this point, in our phone conversation, Aidan stops, pauses and corrects himself: “Yet.”

Aidan told me that he expects Musk to crack down on queer and sexually explicit content—“although he claims to be for free speech, he seems to be very happy to ban anything he doesn’t like,” he says, “so if queer erotica upsets little Musky-boy, I’m out just on that”—but he also doesn’t see much return on investment from marketing on a dead platform.

“So many people I know are no longer comfortable being there,” he says. “If you’re selling queer erotica, you’re selling to queer people. If none of them are comfortable [on Twitter], my customer base just goes away. Even if I stay, who am I marketing to, if everyone I know leaves?”

This isn’t just business. In some cases, it’s a matter of life and death. Trans people habitually pass the hat on social media to crowdfund things like medical care and housing; Twitter, unlike other forums, allows crowdfunding requests to spread quickly to a heterogenous audience, so the requester isn’t just hitting up friends who may be in similarly dire straits. When my savings weren’t enough to cover top surgery, I got the additional money I needed via Twitter. So have many people I know.

Isabelle, an Australian writer who spoke with me by email, was palpably scared—not just about her social life, but about her survival. Isabelle has been disowned by her parents since coming out. She’s lost both jobs—one that entailed working with a choir “composed almost entirely of older conservatives,” and the other teaching. In that time, her health has gotten considerably worse, and Twitter crowdfunding has been her safety net.

“[My] conditions can be managed with the support I’m trying to get, but in the meantime I’ve gone from ‘tired and miserable’ to ‘can’t stand for more than five minutes,’” Isabelle said by email. “When this site goes, I don’t know what the hell I’m going to do; I don’t have a career to go back to.”

Twitter might have been a harassment machine and a free-for-all, but it also allowed people who were normally marginalized, silenced and excluded to make themselves heard. After all, Isabelle points out, even if there was no useful moderation on the bad comments, there was no moderation on the good ones, either: “Criticize a powerful person on their Facebook page or personal subreddit and they will delete it,” she says. “Criticize them in a Facebook group or someone else’s subreddit and they will wheedle or coerce the mods into deleting it.”

On Twitter, the powerful just had to sit back and get yelled at like anyone else. When the platform collapses, marginalized people will lose their networks, their resources and what feels like their only way to make themselves heard in a hostile world.

“A marginalized community is at its least safe when it’s out of sight, because that makes it out of mind,” Isabelle says. “We’re being dragged away from the microphone. What comes after that?”

“I think of Louise Lawrence, a transgender woman who first transitioned in 1942,” Cross tells me. “She made herself a kind of ‘central post office’ for trans people all over the world by placing personal ads in various periodicals—and even reaching out to people arrested for ‘crossdressing’ whose names had been paraded around in the newspapers. She tried to convert that infamy into something positive by acting as a go-between, linking those unfortunate souls with other trans and queer people, all via letter.”

The point, Cross says, is that trans people “have always been able to shape ourselves and our communities on networks designed to destroy us.”

Watching Elon Musk burn down Twitter has left me, at least, feeling powerless; a thousand bullies tried to drive me off the site and failed, but one white dude billionaire can buy the site and destroy it within a week. Trans people have made our social networks, our livelihoods and, yes, even our discourse (maddening as it may be) on networks that we do not own, and that are frequently owned by people hostile to our existence. We’ve gotten so used to this state of affairs that we can forget how precarious it is: Twitter isn’t a “commons.” Twitter isn’t a “public square.” Twitter is a company, and companies go out of business all the time.

Then again, Stonewall was a mafia bar. There’s a long history of queer and trans people taking hostile spaces and turning them into something life-giving, Cross says: “We are masters at using systems not built for us … and whatever comes next is something we’ll adapt to the needs of trans community, because it’s what we’ve always needed to do.”

This is an unexpectedly inspirational takeaway for Twitter, which (again) has always sucked. Yet before we move on to complaining about the next platform, it’s worth considering what trans people did here. We took one of the worst social media sites on the internet and made a home out of it. Just consider what we could do with a place that cared.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra