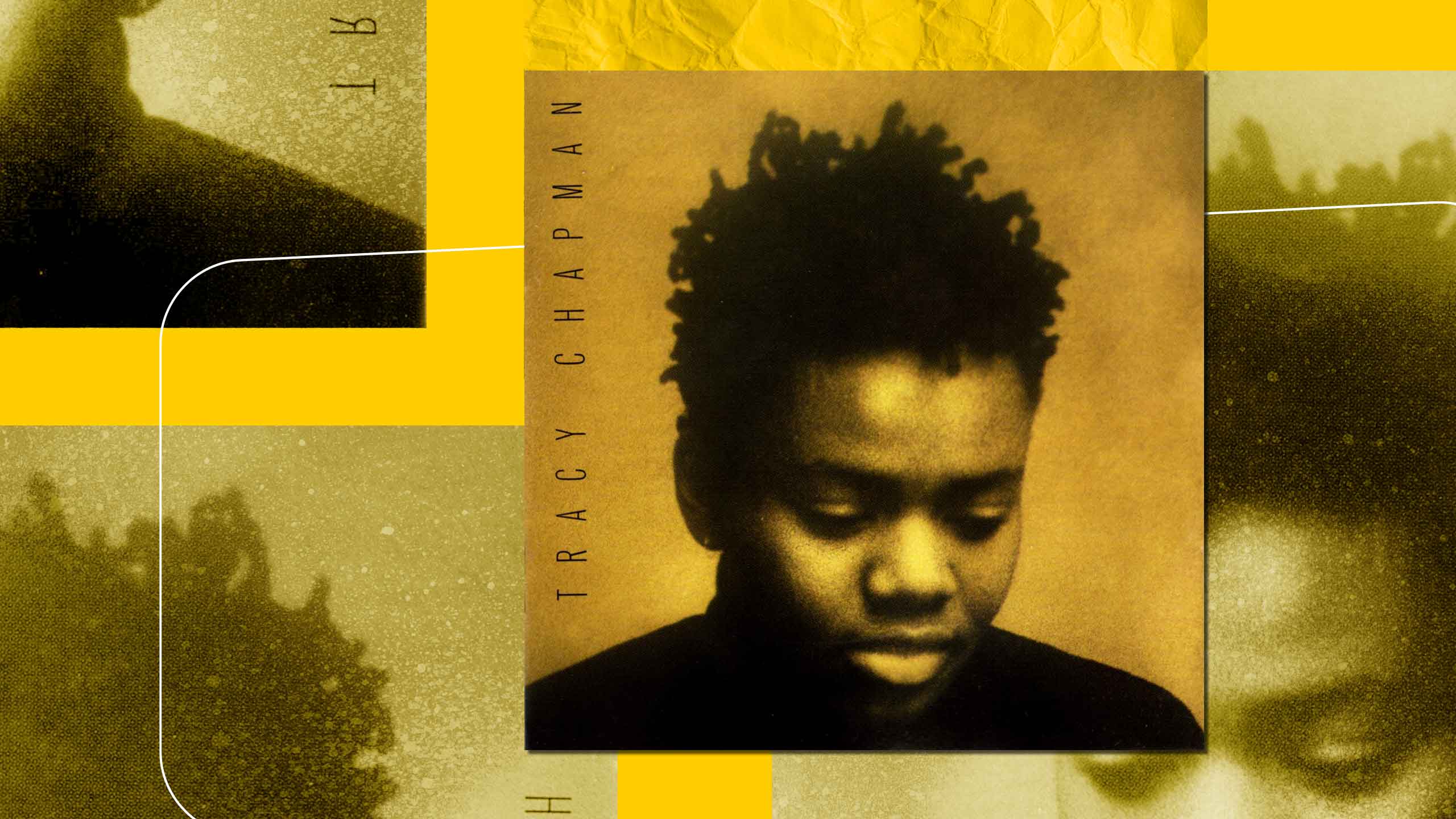

Music is my source of comfort, that thing that automatically eases tension and relieves stress. When the world becomes too much to deal with, I turn to songs that inspire me and have a message that I can relate to. Somehow, the perfect combination of lyrics and instrumentation always helps me feel like I’m not alone. While my process often involves recycling the tracks I know like the back of my hand, sometimes I venture beyond that for something missing from my go-to playlist. That’s how I discovered Tracy Chapman’s 1988 self-titled debut, an album that has single-handedly changed my life.

At only 23-years-old, I’ve already sectioned my life into two distinct eras: Before Tracy and after Tracy. In the before times, prior to knowing who Chapman is, I was already a fan of female singers of her generation: Stevie Nicks, Annie Lennox, Kate Bush. I was a young Latinx woman attending college in Arizona, but living at home in the Bay Area during the summer. Though I was out to family and friends, I hadn’t yet made the seemingly obligatory, public declaration of my bisexuality. Then, in 2018, I needed a break from the news. Donald Trump was still president and his administration was ramping up deportation and detention efforts against immigrants. When I heard and read that they were separating children from their parents, I needed something that would help me feel like there was still hope; I just couldn’t believe the atrocities that were being committed.

“I needed something that could ease the pain of feeling like I couldn’t do anything about what was happening.”

I turned to music for solace, as I typically do. But the indie pop and ’70s light rock I’d normally listen to wasn’t cutting it; I needed something that could ease the pain of feeling like I couldn’t do anything about what was happening. That’s when I stumbled across Chapman’s “Talkin’ Bout a Revolution.” Listening to that track gave me an all-consuming feeling of hope. It seriously made me believe that maybe things would get better, and it convinced me that it was up to my peers and I to work for that better future. After all, the revolution that Chapman talks about doesn’t happen on its own.

“Talkin’ Bout a Revolution” led me to the full album. As I listened to tracks like “Fast Car” and “Baby Can I Hold You,” something else awoke in me.

I was 20 when I discovered the album, a full three decades after it was released. At the time, I didn’t know that Chapman is likely a queer woman (though she was outed by former partner Alice Walker, author of The Color Purple, she’s never publicly declared her identity) or that her genderless songs are also likely about queer women relationships. Upon my discovery, the album immediately became a piece of queer media unlike anything I had consumed before; that’s when life after Tracy began.

Listening to “Tracy Chapman” as a young brown queer person is like sitting down with an elder in the community. Considering there aren’t often many spaces where LGBTQ2S+ people can gather across generations, my love for this album is perhaps the most significant relationship I’ve had with an older queer woman of colour. Any other relationships were short-term or with younger people or white people. I know it might be odd to say something like this, but because I’ve never personally known any queer elders of colour—and considering I was still figuring out when, where and how to embrace my own queerness—Chapman’s words provided guidance.

Take, for example, “Fast Car,” in which Chapman speaks to the experience of being from a smaller town and dreaming of leaving it behind for the big city where queer freedom and safety supposedly reign:

Won’t have to drive too far

Just ‘cross the border and into the city

You and I can both get jobs

And finally see what it means to be living.

Then, later in the song:

You got a fast car

Is it fast enough so we can fly away?

We gotta make a decision

Leave tonight or live and die this way.

When I was a kid, growing up in the suburbs of two bigger Bay Area cities with no known queer people around, I felt like I had nothing to lose and everything to gain by breaking out of my circumstances. I vividly remember when I began thinking that I might be queer my freshman year of high school. Because I didn’t have anyone to talk to about it, I used to dream of moving to New York City and further discovering myself. You can hear in Chapman’s words and the way she sings them that she, too, knows what it’s like to be desperate for such a change. “Fast Car” understands this feeling and conveys it with seriousness, urgency and beauty.

I also deeply identify with “Baby Can I Hold You.” It taught me about queer love, and the perfection of imperfection.

Forgive me

Is all that you can’t say

Years gone by and still

Words don’t come easily

Like forgive me, forgive me.

Chapman sings about a relationship not without flaws.

But you can say baby

Baby, can I hold you tonight?

Maybe if I told you the right words

Ooh, at the right time you’d be mine.Advertisement

This song gave me something I didn’t have before, something that I could hold to my heart as I dreamt of a future where I can love who I want. It taught me not only that being in a queer relationship was possible, but that it wasn’t going to always be rosy; that queer relationships have their own share of the good and the bad, but that it’s all worth it. I know that dreaming of a messy relationship might sound counterintuitive, but most of the queer media I’d consumed at that point hyperfocused on the grandness of coming out. It wasn’t until I heard this song that I truly realized that there’s a life after coming out, one that can be filled with the simple struggle of navigating a relationship. The way Chapman’s voice fills with such wanting throughout the track strikes me to my core.

I can’t overstate how much Chapman’s debut album has been a touchstone for me, one that I return to time and again. It was a jumping off point when I needed a piece of media that spoke to my own newfound queerness. And even now when I revisit it, I get something slightly new out of it. It speaks to the confident, queer woman of colour that I am today and the old me that was in the closet for years, so unsure of my identity. I’m sure plenty of people over the years have remarked about her influence on their lives, and I am no different. Still, I’m grateful for the lessons she’s taught me.

This story is published with support from the Ken Popert Media Fellowship program.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra