June 2022. My partner BR and I walk to a matinee screening of (now six-time Academy Award nominee) Top Gun: Maverick at the Cineplex near us. There’s extra bounce in my step and excitement in my voice. When we arrive, I purchase popcorn in the ridiculous—and ridiculously overpriced—Pete “Maverick” Mitchell souvenir popcorn bucket. This delights and disturbs BR, who has made a grudging exception to her “no creepy Scientologists’ movies” rule to join me for this.

The previous night, we’d revisited the original Top Gun and it inspired the same question it always does: Why is it so damn satisfying? And why is the long-awaited sequel also so entirely enjoyable to me? What has me watching and wondering and rewatching and feeling?

BR is not alone in being rather baffled at the intensity of my enthusiasm. Various friends ask some version of why I, a Gen X butch lesbian feminist, am so excited to see a mainstream, pro-military, Tom Cruise vehicle. “Butch,” soft though I may be, is part of the key here. In 1986, when I first watched the original Top Gun, I’m sure I’d never heard the term.

But I was a 12-year-old tomboy living on a farm in southwestern Ontario, whose chores involved dusting furniture and vacuuming floors while her stepbrother’s included harvesting crops and ploughing fields. Oh, how I’d love to have learned to operate that heavy machinery, too.

Credit: Everett Collection

I was also a teen girl. My friends and I collected Tiger Beat and 16 magazines, plastering our bedroom walls with posters of Hollywood heartthrobs. Cruise-as-Maverick was there above my bed, looking at me with that cocky stare and triumphant thumbs-up from the cockpit of his F14 Tomcat, American flag (of course) as backdrop.

At the time I thought I wanted him—and maybe part of me did. But looking back at the tricky business of my adolescent identifications and desires, I’m sure it’s more accurate to say that I wanted to be him—craved the opportunities and experiences afforded him. I wanted to fly those planes and ride those motorcycles.

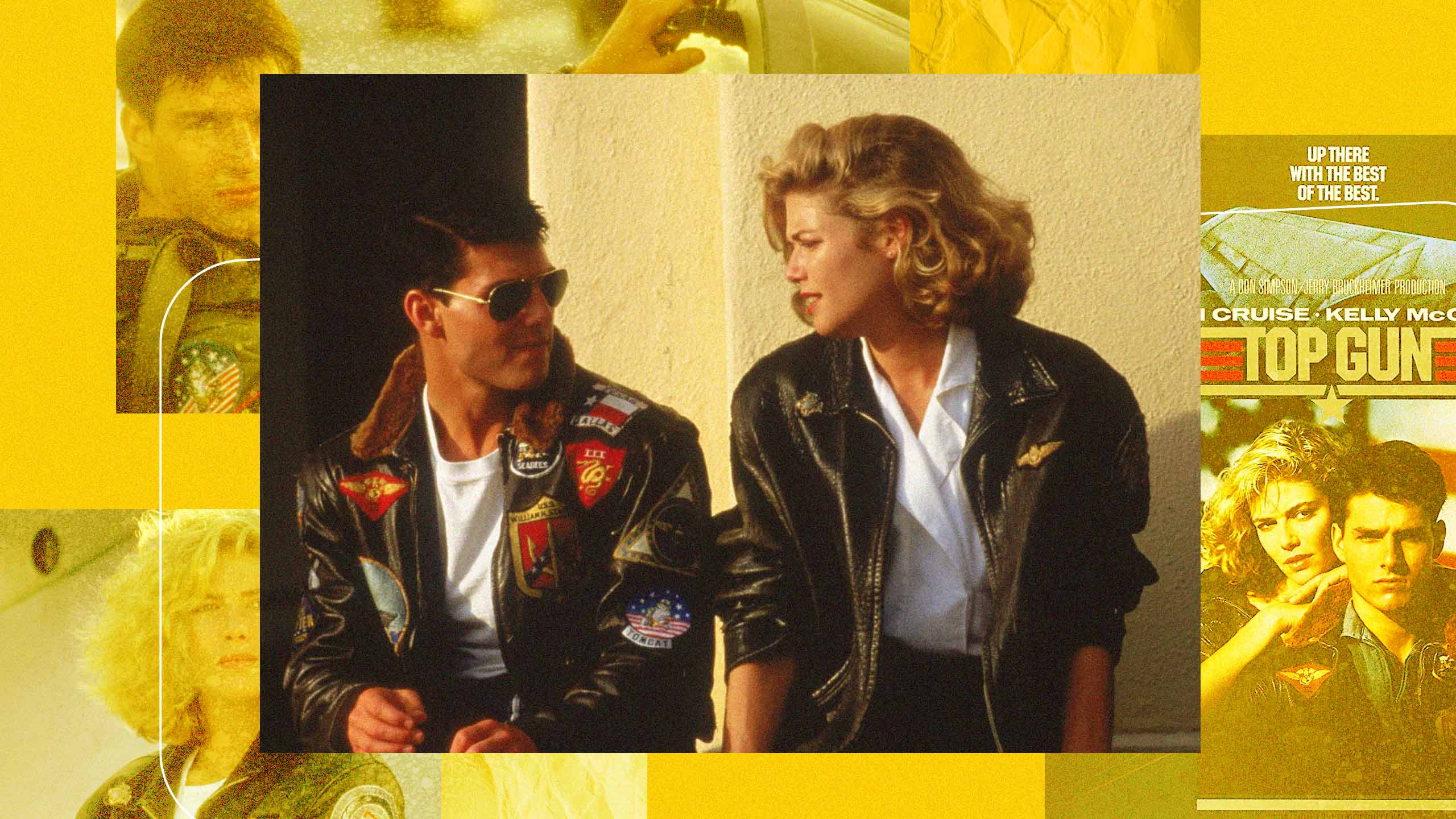

I didn’t yet know that I also wanted to charm the pants off Kelly McGillis (astrophysicist Charlie Blackwood, PhD)—an actor who, two years later, I’d watch with riveted attention opposite Jodie Foster in The Accused. I felt, but couldn’t yet name, the sexual tension between Foster and McGillis, who would both come out publicly many years later. Hindsight suggests that my subconscious gaydar was thrumming.

Fast forward to my first year of university, 1993, when posters of Foster, Mary Stuart Masterson and Susan Sarandon adorned my residence walls (Silence of the Lambs, Fried Green Tomatoes and Thelma & Louise all came out in 1991—a banner year!). My early and late teen decorative choices—the tough-yet-soft hot guy and the soft-but-strong hot woman—forecasted my slowly emerging orientation.

In most of the films that I saw in the ’80s, female characters were predominantly mothers, wives or girlfriends (and/or victims of male monsters). It was the rare movie outside romantic comedies that featured men as primarily dads, husbands or boyfriends. More often, their bonds with other men eclipsed any familial or romantic tie.

I watched men in relation to, and with, each other in countless war, Mafia and action thrillers; in buddy movies and sports (boxing and basketball and baseball, oh my!) flicks. I’m remembering Platoon, Harlem Nights, Lethal Weapon, The Outsiders, Hoosiers, et cetera. There was a plethora of narrative contexts in which men loving men was not only permissible, but celebrated.

Top Gun is a great example of the sort of male homosociality I’m talking about (there were no women in the original Top Gun class, remember). It showcases handsome aviators double teaming, tapping in, bottoming out and chasing each other’s tails while dogfighting in the most phallic of objects. It revels in over-the-top locker-room banter and beach volleyball courts filled with sweaty, half-naked men all vying to come out on top.

Indeed, the boys play so hard with and against each other that Top Gun was deemed (more than) a little gay from the time it dropped. Quentin Tarantino (as Sid) popularized and immortalized this take on Top Gun in Sleep with Me (1994). In a legendarily improvised monologue, he offers a delightfully manic case for the film’s ultimately savvy depiction of repressed homosexuality.

Buy this interpretation or not, the intensity of the masculine bonds in Top Gun is undeniable. As the class battles it out for the coveted Top Gun trophy, ultimately teaming up to defeat their “real” enemy (never overtly named, but most likely Russia), they become a family replete with requisite love and dysfunction. They form a profound brotherhood that I watched with fascination, curiosity and envy.

In school, my membership on girls’ sports teams (baseball, basketball, volleyball) offered me the closest equivalent to the homosocial environments and attachments, the revelries and rivalries, of Top Gun. I relished time with teammates, as much for the attendant rituals as for the games themselves: practices fuelled by intra-team competition (no shirts and skins for us—boxy, sweaty pinnies instead) and energizing music we curated on cassette tapes; pre-game strategizing and post-game debriefs; trash-talking the competition (and each other); pumping each other up and dressing each other down (mostly teasingly, sometimes seriously). We gave each other shit, got into some shit—and it was the shit.

But where were the filmic sisterhoods? I felt left out, lacking big-screen mirrors of and for my own experiences in the world. My early frustrations with inadequate, unsatisfying film representation inspired a passion for feminist criticism that wasn’t exactly popular with my high school peers. Where were the scripts in which the exploits and attachments (and maybe even locker rooms) of women reigned supreme? (Alas, these remain salient questions). I lamented the dearth of women generally and women together specifically—and especially.

Still, I loved Top Gun.

Many years later, what I remember about the film is not the air combat or the heterosexual manoeuvring. Instead, what I recall most powerfully and specifically is the Maverick-Goose love story, Goose’s death and the ensuing tale of Maverick’s mourning. The film has an emotional heart, and this is it.

Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick’s now classic—I dare say it was an academic blockbuster—Between Men: English Literature and Male Homosocial Desire (1985) articulated structures of identity and desire in men’s fictional relationships. She identifies a curious, powerful and prevalent (I swear, once you see it, you see it everywhere) triangulation: desire (sexual or not) between men is rendered safe, palatable and unthreatening via a woman who functions as the guarantor of an obligatory heterosexuality.

Launched just a year later, Top Gun is Sedgwick’s thesis writ large—in skywriting and dressed for Hollywood. Charlie’s presence renders permissible the profound love between men here. The original trailers, billboards and VHS cover art foreground a heterosexual romance that is, in the film proper, more compulsory than convincing. Amusingly, one of them perfectly, if unwittingly, literalizes the very triangulation Sedgwick describes—erect fighter jets and all.

Credit: Everett Collection

With outsize chemistry and a broad emotional range, the Maverick-Goose friendship fuels the film: its action, its comedy, its drama—and, ultimately, its tragedy. Romantic wingman, flying RIO and symbolic father figure, Nick “Goose” Bradshaw is “the only family” Maverick’s got (both of his parents died when he was a child). They joke and tease, talk seriously and vulnerably—especially when Maverick’s hijinks put them in danger.

It’s Goose who calls him on his brand of exaggerated bravado: he tells Maverick that he makes him nervous because “every time we go up there, it’s like you’re flying against a ghost.” (Wonderfully, their squadron aircraft call sign is Ghostrider.)

Maverick’s most touching moments in the film occur either with Goose or with Goose in mind. In the wake of Goose’s death, Maverick’s grief finds longing expression in his oft-repeated imperative-cum-mantra, “Talk to me, Goose.” Moreover, as writer Jesse Pennington notes in a piece for Salon, the beautifully haunting melodic riff “Memories” (written by Harold Faltermeyer) is established as the soundtrack of Goose and Maverick’s friendship, and later becomes the musical leitmotif of Maverick’s mourning in this film that is less “macho mystique” than “male vulnerability.”

Goose’s death is not the only loss that troubles Maverick: from the outset, he’s already a man in mourning for the father (call sign Duke) whose mysterious Vietnam war death haunts him, in part because he doesn’t really know what happened. Maverick mourns the death of his dad and the missing story of that loss—struggling with the elusiveness of a (kind of) knowledge he believes exists but can’t access.

Rather ironically, given, you know, militarism, death and mourning confound the mindset that values the cut and dried, straight (in all senses of the word) and narrow. As writer Meg Halstead argues argues in a piece for Talk Death about the complicated, layered grief and intergenerational trauma in Top Gun, Maverick is instructed to “get used” to losing people and to “let go” immediately and move on: “Not only is Maverick forced to contend with a new grief atop the old, but his grief experience is always disenfranchised by his superiors.” Explicitly and implicitly, the message is that grief crosses a line, mourning a real danger zone.

No one important to me had died when I first saw Top Gun. Rewatching it today, on the other side of significant personal losses, Goose’s death hits differently. Now when I watch that brief and oh-so-quiet scene in which Charlie drops Maverick off and he slowly shuts her car door, directly expressing his pain—“God, I want him back”—it hits hard. There is more desire and longing in that delivery than anything that happens between Maverick and Charlie. That’s the love story that takes my breath away.

Credit: Paramount Pictures

Militarism and heterosexuality function not as the subject of this Hollywood vehicle, but as the safe scaffolding for the risky business of love—yes, even platonic—between men. For all its often-laughable machismo (the dick and butt jokes, the campy call signs), disturbing misogyny (Maverick’s pursuit of Charlie alternates between stalking and negging) and American exceptionalism, there is something else and other here. And it’s those stories of more vulnerable, softer masculinities that I love and with which I clearly identify.

And yes, I loved the long-awaited sequel, which I saw three times and keep mistakenly calling Top Cruise, much to BR’s delight. The new crew is fun (and, hey, there’s even a woman or two). Miles Teller is good as Goose’s son and Maverick’s protégé, the always-mourning (and often brooding) Rooster.

But Goose is what’s missing from—what I’m mourning in—the sequel. The spectre of his presence haunts the narrative, but the heart he brought and the character chemistry he provided are mostly absent here, save a heartbreaking final scene between Mav and Iceman (Val Kilmer) in a nice nod to the past.

I love Top Gun: Maverick less for the film “itself,” however we define that, and more for how it makes me feel. As soon as it begins and I hear the opening bars of the stirringly familiar “Top Gun Anthem” (also composed by Faltermeyer), I’m already emotional. This is where the film gets me.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra