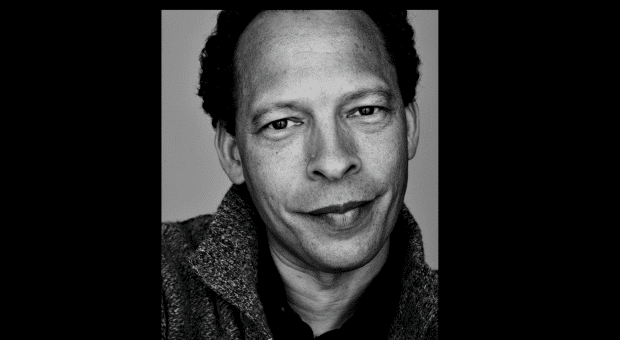

Blood is the most vital substance we know. It flows in all of us, deep red, carrying the oxygen we need to live and the baggage of more than 200,000 years of history. For as long as there have been human beings, blood has been the subject of ritual, medicine and legislation. Blood: The Stuff of Life, the newest book from Lawrence Hill, author of The Book of Negroes, is the subject of the 2013 CBC Massey Lectures. It examines how blood has shaped our thoughts and deeds in matters of race, gender, politics and class. Xtra spoke with the award-winning writer about how blood continues to affect us.

Xtra: Obviously the ideas of race and genetic history are a pretty significant theme in your writing. Can you talk about how you decided for this book to focus on blood as a vehicle for some of those issues?

Lawrence Hill: I started to think about blood as a unifier and a divider of humanity. I’ve always been interested in social histories of objects, like a social history of coffee, for example, will tell you a lot about social inequalities in the world. A social history of sugar will also tell you a great deal about the nature of humanity, and so coffee, sugar — why not a kind of a social history and a historic meditation on blood and all the different ways that it speaks to us and brings us apart and divides us?

When we talk about blood from an LGBT perspective, one of the first things that come to mind is HIV/AIDS and the idea that we can actually use blood to sort people into categories of “diseased” and “healthy.”

[Blood] definitely can be a lifesaver in a literal medical way, but it can also obviously be a killer. It can be a killer if a mosquito bites you and it has encephalitis or malaria or something, West Nile disease, and that disease kills you as it does many people in the world. Or it can be something that can kill us, or we fear could kill us, through sexually transmitted disease. So I think that what’s happened with blood is that as the world has expanded and as the propagation of disease has expanded, we’ve become paranoid and very fearful about our safety and about our blood safety, and so unfortunately, HIV has become kind of a dividing line, and we have chosen, wrongly, in society to stigmatize people who have it, to isolate them, and also to be overly fearful of catching it if we don’t already have it. I think that that fear, the fear of sexually transmitted disease, the fear of picking up somebody else’s illness, the fear of dying from HIV or AIDS, is still quite palpable, and it translates into tremendously discriminatory practices against people in the LGBT community, especially after the tainted blood scandal that arose in the 1980s, when the fear was so incredibly high.

This brings up the issue of the Canadian Blood Services’ ban on gay men donating blood, which was recently lifted but with the stipulation that they must be celibate for five years. Obviously, it’s been lifted in name only; how do you think that ideas of cleanliness and fear have shaped our attitudes and policies surrounding blood safety?

I like to compare it to what happened at the time of the Second World War. For the first time we had the technology to remove and store and then safely transfuse blood, [and] just as we were acquiring the technology to do so for the first time ever, we in North America, specifically the American government and the American Medical [Association], passed rules making it impossible, illegal, for black people to donate to white recipients . . . Even though it was fully understood that there was no medical or scientific difference between bloods of so-called “races,” still the decision was made.

So just like people were segregated by race, so was their blood. It had nothing to do with science and medicine and everything to do with social discrimination. I would argue that the same thing is true now in terms of the blanket ban on blood donations by gay males. It’s ridiculous to have a five-year ban. Who will that allow to donate? What sexually active, healthy person is going to be abstinent for five years in order to donate blood? It’s ridiculous — it just seems like a Canadian compromise to a silly extreme. I can’t see how that five-year rule really makes any difference to anybody who’s living actively, and I don’t understand why in this day and age it still seems necessary socially to ban all gay men who are sexually active from donating blood. It seems like a blanket that’s far too thick and wide, and it taints a person by dint of their sexual orientation when what really should be at issue is the safety of their blood, not their sexual orientation.

Another issue that comes up in the book is the idea that by quantifying the makeup of blood we can determine things like gender, status and race. How do you think this ties into our ideas about things like purity?

Impurity of blood is always a way to demonize a person and to justify the most hideous act that humanity has ever perpetuated: mass genocide. So when we want to take a person and make them seem sub-human so that we can attack them or lower them or treat them badly, whether it’s a slave or whether it’s a genocidal victim, we tend to try and establish that there’s something wrong with their blood. And so that extends, of course, to the fears that people have now regarding the blood of gay male donors.

If one is to try to demonize or dehumanize people, including in the LGBT community, often the most pernicious way to do it is to somehow taint their blood and suggest that there’s something wrong with their blood. And so people still have this great fear of gay males donating blood, even though I think the litmus test for each individual donor should be, are they safe? Are they safe donors, period, and can this be verified? Not what is their orientation or how do they define themselves in terms of their gender. So yes, I think that whether it’s a black person at a time of overt racial segregation in the United States or a person today suffering from homophobia, blood seems always to be the thing we use to justify discriminatory treatment . . . It always comes down to the symbol of purity and the symbol of what’s sacred to us, and it interferes in a negative way when we tie it to purity. It interferes sometimes with our ability to treat people with decency and respect regardless of how they’re living.

In the book you talk about how menstruation has tended to be viewed in many cultures as evidence of women’s weakness and what that has meant for women and feminine individuals.

It seems that just about every religion in every country has found a way to stigmatize women because of their blood and because of their monthly bleedings, and I’m fascinated in how thoroughly inept men have been over the millennia . . . in understanding women and their monthly blood. It confuses us, it befuddles us, we don’t know what to make of it, and we’ve come up with, over the course of thousands of years, the most ridiculous theories to try to explain it to ourselves and to others. It ends up being another way of justifying sexist treatment of women. Not allowing women to have certain jobs, not allowing women all the rights and freedoms accorded to men. All of these things often can be traced to notions of women and their inferiority or their impurity because of their monthly bleedings. I really do feel that it has permeated just about every level of the way that we think and talk about women.

We also use blood as a way to create rules that apply to others, particularly in the case of parenting. Historically, many policies have stated that based on the makeup of a person’s blood, they are unfit to parent their own children.

My observation is that historically and still today we tend to identify and quantify people by their blood parts, as if we really could do such a thing . . . It’s a ridiculous notion and it’s easy to ridicule, but the sad truth is that, ridiculous as it seems, we still resort to it in our thinking, in our courts and in our legislatures. Blood still looms very large in the way that we make practical, tangible decisions about how people will be ruled over and defined.

I think we have this ludicrous and very harmful notion that the only authentic relationship is one that is based on a blood tie. So if you have a biological child, that’s an authentic relationship. But heaven forbid if you adopted a child, or you got a child into your life through some alternative means. If you’re a step-parent or if you’re in a gay or a lesbian relationship and you’ve brought a child into your relationship, many people will assume that that’s a second-class relationship. It doesn’t pass muster, it’s not as legitimate a relationship as the real thing with a biological father and a biological mother and one child standing between them. And it’s a very dangerous way of thinking that biology sort of trumps love, trumps faithfulness, trumps devotion and caring and respect among people. It trumps the creation of human relationships.

Blood: The Stuff of Life

Lawrence Hill

House of Anansi

$19.95

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra