In the current CanStage production of Bernard Pomerance’s 1979 hit The Elephant Man director Robin Phillips has his cast surrounding the title character all asking the same question. Staring blankly into the audience, their backs to one of history’s most famous “freaks of nature,” they all, one after the other, respond to the query, “Who does he remind you of?” Unanimously, they say that he reminds them of themselves. The strength — and weakness — of the script lies in this simple answer.

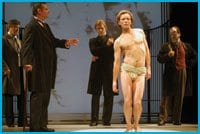

The CanStage production, although powerful and engaging, is true to the parable-like quality of a script that consistently over simplifies complex issues in order to deliver a universal message. This quality — in life and art — is not lost on lesbian and gay spectators who may have encountered simplistic forms of objectification and undo categorization during their lives. By casting beautiful men in the central role, ideas of beauty and physical identity are challenged throughout the play. Over the years the part has been played by actors such as David Bowie, Mark Hamill and Billy Crudup. Brent Carver’s current interpretation is consistently powerful as he spends much of his time onstage in a diaper-like costume that his subtle and skillful physicality renders both elegant and pitiful.

Like many classic, universalizing scripts, notions of fear and pity run throughout, marked by lighter comic moments. This comic quality is best represented by the character of actress Mrs Kendal, played beautifully by Kate Trotter. By blending varied forms of acting techniques from the 19th and 20th centuries, she reveals the cumbersome, erratic and very human lines that are often drawn between reality and illusion. Her attachment to John Merrick (the Elephant Man) becomes a focal point for the play and provides the audience with some extremely moving and frequently uncomfortable sexualized moments.

Geraint Wyn Davies, as Dr Treves, delivers an appropriately restrained performance that empowers the passion and emotional surrender of his final scenes. The remaining cast including Jack Wetherall, Michael Spencer-Davis, Barry MacGregor, Michelle Fisk, David Kirby and Aaron Forward create a strong ensemble effect crucial to the success of this delicately balanced morality tale. Sherri Catt’s set design and Sue Lepage’s costumes provide a fine blend of classic Victorian with sleek contemporary lines and complement Phillips’ often geometric, stylized staging and acting strategies.

It would have been very simple to present this 28-year-old play with an overemotional reverence that focused on the sensationalist freak shows that continued to litter the countryside worldwide well into the last century and finds counterparts in 21st-century tabloids and online sites. Phillips, however, has risked a more deliberate, less spectacle-oriented approach that forsakes an onslaught of emotional abandon in order to highlight the universal ideas that the play explores. This strategy gives the central character a great deal more dignity than any of the characters surrounding him and, ultimately, questions notions of dignity and respect in a world where freakishness — in its many misunderstood forms — continues to sell.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra