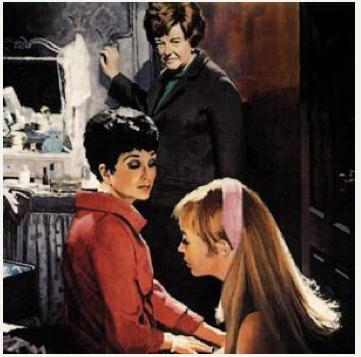

In the last century lesbians used fashion primarily to convey their sexual identity, as for example in the 1964 film The Killing of Sister George. Credit: Ablestock

While gay men are widely recognized for their sense of fashion and often called upon for advice, the idea of a chic lesbian style remains a closeted anomaly. But just because lesbian style isn’t fully appreciated doesn’t mean it doesn’t exist.

To understand how lesbian vogue has evolved let’s start with how it was first depicted in the mainstream. In The Killing of Sister George, released in 1964 and apparently the first Hollywood film to portray a lesbian character, the filmmakers depicted the ways in which many real lesbians of the time produced gender roles through style via their starkly opposite lead female characters. Sister George was as virile as a man in her concealing suits and slicked-back up-do, in contrast to her lace and lingerie-wearing, fragile femme lover.

In the last century lesbians used fashion primarily to convey their sexual identity. By juxtaposing butch/femme identities lesbian style was tied up in playing out these gender roles, signalling that you were one and that you were, theoretically, looking for the other.

Lesbian fashion today still seems to defy convention by creating space for butch style. It’s clear from the images of hyper-feminine women splattered all over the media that there’s little room for butchy women in the mainstream.

But even though the lines between butch and femme have blurred over time, dyke about town Jen Neales says it’s still easy to identify both camps on Church St.

“There are those women who appear more loose and baggy, like a dance to hip-hop style, with a ball cap,” says Neales, “but then you also have women who are super-femmed up with stiletto heels and long hair.”

Obviously today we have a greater diversity of representation of races and faces in the lesbian scene that complicates matters.

While some women continue to dress in accordance with gender roles I’ve also seen a surge in visibility of the chameleon dyke. These chameleon dykes seem to primarily found in the Parkdale scene, mixing and matching traditionally butch and femme styles.

Neales, 28, is a good example of this evolution in dyke style. An actor by profession, Neales compares her personal style to her craft, claiming she plays with gender through her choice of clothes based on how she wants to represent herself at any given time. She admits that her genetics enable her everchanging look — her body is quite boyish while her face is soft and more feminine.

The emergence of the chameleon dyke has become particularly visible to me in the past year or two and I now classify my own style as being in keeping with these modern hybrid lesbians. While I am a sucker for purses, necklaces and earrings and have a special affinity for bling, I feel most comfortable in flats and casual pants. I think this eclectic mix that typifies chameleon dyke style shows the true diversity of the women in our community and is a testament to how adaptive our sensibilities really are.

Naturally this leads me to the laws of attraction. We are all attracted to people for a variety of reasons, but style does play a part. While I am attracted to women who appear more feminine in style, Neales says she would be all over a boyish woman with a loose fitting pair of jeans. For her the attraction is in the elusiveness, “knowing that there is a woman’s body that lays beneath the clothes.”

Of course when considering lesbian style we can’t forget to touch on the crowning glory of our dykedom — our hair.

“While some women like to keep it looking feminine with long hair, others like to style their hair in more male-inspired cuts,” says Karen Conforzi, a stylist at Salon One in the heart of the gaybourhood.

Conforzi notes that a few years back mohawks were huge with her lesbian clientele, but that now the preference is for cleaner, asymmetrical looks. I would argue that these edgier cuts are most likely to be found in the look of the chameleon dyke — it adds to creating an overall androgynous style. That willingness to experiment is yet another example of the malleability of lesbian style that exists today.

Maybe that’s just it — lesbian style is no longer so strict. You no longer have to look a particular way to be recognized as a dyke. Now it can be about being yourself, however it is that you feel comfortable. Though I still can’t wear heels, I can wear myself.

We have come a long way from the days of The Killing of Sister George and straight women could learn a thing or two from our sense of fashion freedom. Though others may not choose to notice our sense of style, they can’t argue that it’s not our own.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra