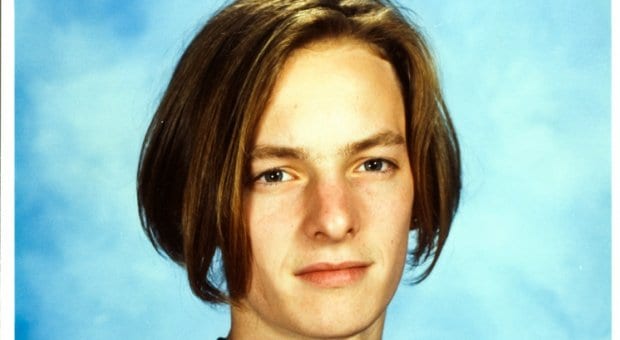

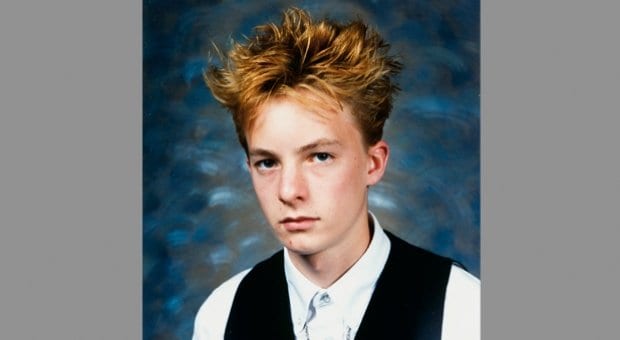

Will Munro in High School

Will Munro died on May 21, 2010, at the age of 35. Many knew him as a cultural innovator. He was also a friend, a son, a younger brother, an uncle and, to a few men, a lover.

Army of Lovers, written by queer cultural critic Sarah Liss, is a love letter to Munro and his family, friends and adoring fans. The book is a collage of voices, photographs, essays, historical documentation and stories as told by those closest to him. Rather than focusing on a single talent, Liss gives the reader an overview of the breadth and reach of Munro’s impact on music, fashion, art, community, politics and business in Toronto and beyond.

Liss begins her portrait with a dramatis personae introducing her many interview subjects, telling us who each person was in Munro’s life. The book consists of three parts; it’s conversational in tone and each section begins with a textured, well-crafted essay by Liss. Part I is Munro’s early life, from birth to his Ontario College of Art and Design days. Part II is about his growing art practice, social circle and fame. Part III is about his failing health, cancer diagnosis, treatment, final art exhibition and eventual death.

Those interviewed in Army of Lovers are Munro’s immediate family members, friends, musicians, artists, caregivers, business partners, ex-boyfriends and drag superstars. A few interviewees distinguish themselves through their honesty, others with their sense of humour, observation and commitment. Especially poignant is Bennett JP’s breathtaking, almost poetic, description of his brief sexual affair with Munro.

We learn much about Munro’s early life from his family — his mother, Margaret; his father, Ian; and his older brother Dave are brutally honest. They don’t hold back in discussing a family that often found itself in crisis. Their contribution is commendable for the powerful confessions they provide.

Peter Ho was Munro’s last boyfriend. The insider details he offers are often sad, but there are moments of joy. The intimacy and trust the two lovers shared is obvious when Ho speaks of Munro’s home life and time in palliative care: “He became a very mean person because he was sick. He was very hard to deal with to a lot of people, but never to me, because we had a different relationship from everyone else. I never felt pressured by it, but Dave [Munro’s brother] especially loved me so much because he could see that anytime I’d come home from work or to visit the hospital after not being there, as soon as I walked into the room, Munro was so happy. He changed immediately, and that meant a lot to Dave. I didn’t really see it at the time, because that was the Munro I saw. But Dave said, ‘He’s such a different person around you.’ And Munro trusted me — he didn’t open up about anything to anyone. He was so closed off about his illness, which made it really hard for me at times because I was his only outlet as well. Sometimes at home he would have fits of crying because he was scared of dying.”

On a personal level, the book works on its own terms and on mine as well. I was hesitant about reading it and dreaded reviewing it because I did know Munro, and I didn’t want to pretend that I didn’t. He was always late, he always had an excuse, he didn’t return most of my phone calls, he could be mean and bitchy and talked about me behind my back. In death, Munro is becoming über and less human, but he did have faults and flaws like everyone else. Thankfully, some people Liss interviews do not shy away from what some might refer to as Munro’s “shortcomings.”

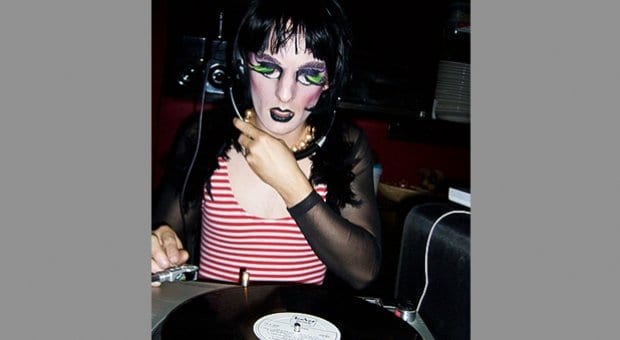

For example, Lex Vaughn says, “And bitch would gossip! Oh my god, he gossiped more than anyone I knew.” With regard to Munro’s art practice, Cecilia Berkovic says, “He was a total rip-off artist. He had no qualms about reusing images, even if it was other artists’ stuff. There was a kind of levelling in terms of imagery, and this irreverence. He just felt like anything could be appropriated.” Ex-boyfriend and best friend Alex McClelland says, “He was horrible at talking about his feelings. He told me a couple of times that I was one of the few people he really loved, was in love with. But he would never say to me, ‘I love you.’ Never, the entire time we were together. He was horrible at expressing his emotions. He’d find other ways, through actions and stuff.” Liss reminds us that Munro was all-too human, with many skills and a few occupations: “He was a crisis counsellor, a line cook, a skilled seamstress, a roller skater, a drag diva, a cheapskate and a drama queen.”

Liss contextualizes Munro’s death in Part III. She plays with time, which flips in a non-linear fashion through the sublime emotions felt by many as they dealt with the reality of Munro’s illness. Imagined time, real time and historical time are questioned, examined and slowed down. All of us were lost. The world shifted. Time stopped. Liss gives us a chance to breathe. She allows us to take a long pause because she knows, that we know, how this story ends.

Liss says that the process of researching and writing a book that already had an ending was powerful and joyful. “Often, interviews would last for an hour or more — Dave talked for almost four hours straight — and afterward I’d feel drained and as though my heart was too full. But Munro was also the subject of so many hilarious, bitchy, over-the-top stories, so these intense, harrowing conversations would swerve and become something between joyful and hysterically funny.”

Army of Lovers is so fascinating it’s already earned a place on the mandatory reading lists of high school and university queer-studies courses, in my opinion. Its pages should be torn out of the book and wheat-pasted on every weirdo kid’s locker in every high school in every suburban hellhole. Because of Will Munro and his army of lovers, we all possess a past, present and future worth celebrating. His life was more than just a big queer dance party. Through his many endeavours he helped us trace our lineage, highlighting connections to larger communities and histories. He did all this while wearing boy’s Y-front underwear — the cheap ones, of course. In the words of Munro, “The freakier, the better.”

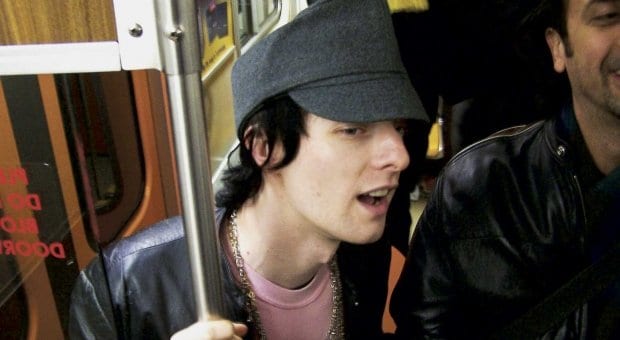

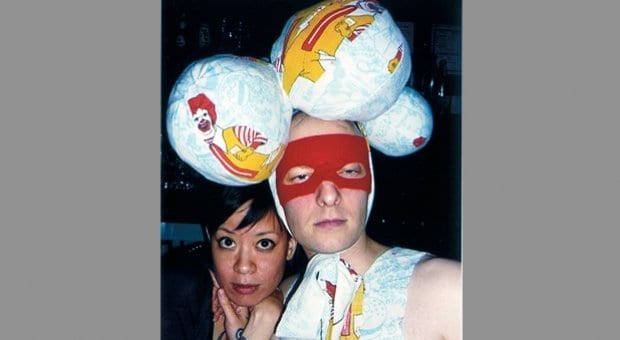

Party monster

Promoted through the hand-distributed flyers and posters that would later become known as artworks in their own right, Munro’s legendary parties served as a community meeting point in the pre-social-media era. Here’s our list of his best-known bashes. — Chris Dupuis

Vazaleen

Originally called Vaseline, this was the rock-and-roll night that started it all: Super 8 porn, lube wrestling and bobbing for buttplugs, blended with a decidedly un-Village fashion aesthetic — it launched the careers of stars like Peaches, Crystal Castles and The Hidden Cameras.

Peroxide

The electro/new-wave night at Kensington Market’s Club 56, a dodgy basement firetrap with a saltwater aquarium. Focused on music in lieu of live acts, the event brought out kids hungry for the hot tracks flowing from Berlin and Munroiamsburg.

No TO

His no-wave/punk-funk night at Thymeless Bar became a meeting point for straights and queers alike who bonded over music that was truly not being played anywhere else.

Moustache

Munro’s strip night at Remington’s was a tiny step back toward the neighbourhood he’d originally sought to escape. Amateurs whipped it out onstage alongside professional peelers, and he convinced the bar to allow women inside for the first time ever.

Miserable Mondays

Commiserating kids knocked back whiskey and listened to The Smiths, until they found themselves happy in the haze of a drunken hour.

Love Saves the Day

Munro’s house and disco party saw him reclaim the music of the Village for Queen West on his own terms. One of the last events he planned, it continues today at The Beaver in his honour.

Army of lovers

By Sarah Liss

Coach House Books

$13.95

chbooks.com

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra