“I think that a black poet can do one of two things for his people,” wrote author Pearl Cleage in 1970: number one, “Reflect the beauty of their black life; whole, broken and mending,” and number two, “Lead them in a righteous direction by showing them the path and what lies ahead in liberation and victory. If you call yourself a black poet and you ain’t doin’ that, you ain’t bein’ truthful and you ain’t bein’ fair and in general, you ain’t doin’ nothin’ for yr people/yr self/the struggle/the nation/the community. In short, you ain’t doin’ shit.”

“I wrote it for myself but I also wrote it for others,” Pasipanodya says, “and I wrote it for Treddah, one of the women who raised me who’s still in Zimbabwe. She is the epitome of grace for me, always full of love and moving with life as it comes, very present in the moment and full of laughter. She was so human and that’s a life goal for me, to be that human.”

“Part of the book,” she continues, “is about just taking off some of those coats and baggage I’ve been carrying and just have it all sit there on a page for people to look at. It’s a letting-go for me and I hope it gives other people hope and permission to take off their own stuff.” While the act of writing has been a saviour of many an author’s psyche, Pasipanodya credits the process of creating Grace with her literal survival.

“When I wrote the book, I had gone through a breakdown of sorts and thought, ‘I should write about this . . . Writing helped me get through it.” There were no suicidal thoughts but definitely one afternoon when, she says, “I was super-depressed but my cousin was with me and she was the only thing keeping me awake and alive at that moment. In her being there, I felt I could be sad and be around somebody. That was a big lesson for me.”

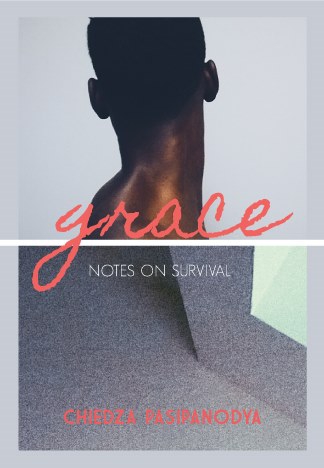

Pasipanodya took a couple photos that day, now among the many that accompany the bittersweet poems in her book. “They were part of the process,” she says, “Moments where time is passing and I’m still here. Barthes said that when you take a photo, it immediately implies the thing existed. By taking photos, I’m documenting my survival.”

The languid beauty of her photos, most of them shot around Toronto, complement her poems as they weave through themes of loss — the end of relationships, the passage of time, the finality of death. “The words may be comfortable or not comfortable,” she says, “and the photos allow for a resting place between that discomfort.”

Closing

the dead are not dead, they are living in our mouths.

the dead are not dead, they are flowing through our minds.

the dead are not dead, they are blooming in our lives.

Grace: Notes on Survival more than fulfills Pearl Cleage’s instructions, both the vital first and the inspiring second, but the beauty of its images work some healing magic both universal and specific. In the end, Pasipanodya says, for all of us, “it’s about just being open to the moment. Always tell yourself the truth, that’s when grace comes through.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra