It isn’t every day that Hollywood releases a star-studded prestige production celebrating the life of a man once considered among the most dangerous in America. Writer-director Bill Condon, whose Gods And Monsters was another acclaimed queer biopic, has crafted an energetic film that is as candid and enthusiastic about human sexual diversity as was its pioneering protagonist, Dr Alfred Kinsey.

Kinsey dragged the discourse around sexuality from the moral arena into the domain of science through his incredibly influential studies Sexual Behavior In The Human Male published in 1948 and Sexual Behavior In The Human Female from 1953. He saw sexology as a means of combating stigma by proving that behaviours then considered perversions were common and therefore normal.

Obsessed with studying life since childhood, the biologist’s passion for sexology originated in his own problems in the bedroom. Rather than feeling ashamed, he assumed that everyone must share his ignorance about sex and should have the resources to find out the facts, not puritan myths.

Condon could easily have directed a conventional, straightforward film about a heroic man of science, but what is so pleasurable about Kinsey is its dynamic sense of playful exuberance and experimentation. While the film does veer into sentimentality, Condon balances the drama with bold sequences using techniques familiar from documentary: witty montages illustrating his interviews with thousands of Americans about their sex lives, the massive social impact of his findings and, behind the end credits, how different species copulate.

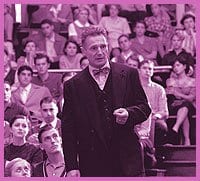

The brilliant, stubborn, twitchy Kinsey is brought to life in a mesmerizing performance by Liam Neeson. Laura Linney is remarkable in the role of his partner, Clara. Fiercely intelligent, loving and strong, she is also clearly challenged by the practical implications of Kinsey’s ideas. The cast is rounded out by John Lithgow, Peter Sarsgaard, Chris O’Donnell and Lynn Redgrave (as a weepy lesbian).

The film slips slightly when Kinsey delivers an impassioned speech against paedophilia (breaking his own rule of never judging his subjects) in an incongruous scene that seems designed expressly to relieve the potential concern that his open-mindedness knew no bounds. However, the film does not shy away from subversive material: Kinsey’s bisexuality and his drive to experiment on his own body are overtly represented, and scenes of an elderly woman getting fucked and illustrations of venereal disease are more graphic than one would expect from a Hollywood film.

It is totally refreshing to see people speak openly about sex – generating ideas that would contribute to queer identity and theory – in the 1940s and ’50s. In many ways, Kinsey is as taboo-breaking as its subject; it is a pleasant surprise that such a tony production can be so queer.

Kinsey opens Fri, Nov 12.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra