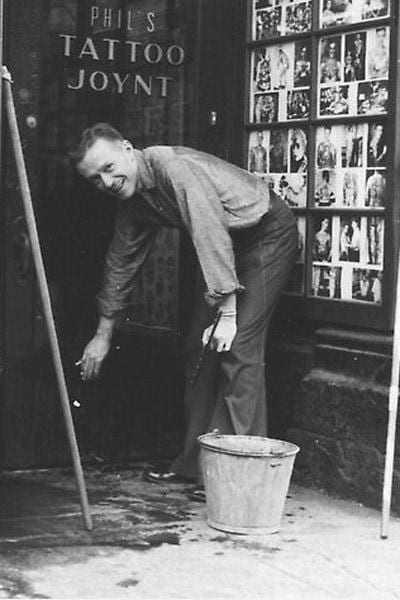

Steward at his Chicago tattoo shop in 1957 Credit: Courtesy of the estate of Samuel Steward

In his new book, Secret Historian: The Life and Times of Samuel Steward, author Justin Spring attempts to salvage the reputation and legacy of a mostly forgotten author, intellectual, pioneering sexual archivist, pulp pornographer, masochist, bon vivant and unrepentant homosexual.

Beginning as a promising bright light of the interwar literary avant garde scene, Steward settled into an academic life at a Chicago Catholic university, only to completely reinvent himself at middle age as pioneering tattoo artist Philip Sparrow. He subsequently went on to publish highly literate gay pulp fiction under the name Phil Andros. These are only two of a long list of Steward’s noms de plume.

During the 1950s, Steward’s life was an elaborate double-act: by day, professor Samuel Steward, Phd, popular teacher at DePaul Catholic University; by night, Phil Sparrow, one of Chicago’s foremost tattoo artists, friend to gangsters and seducer of naval cadets and back-ally street toughs.

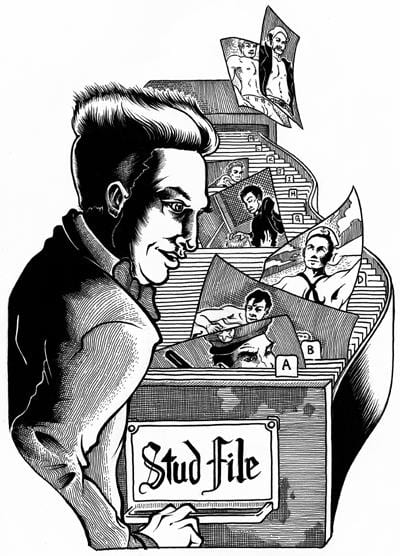

One of Steward’s most lasting imprints on history is his role as a sexual archivist and researcher for Alfred Kinsey’s Institute for Sex Research. Throughout his entire adult life, Steward maintained an obsessively annotated Stud File containing hundreds of index cards detailing every one of his 4,647 sexual encounters with 807 men over nearly 50 years.

His Stud File became an indispensable record – spanning most of the 20th century – of the evolving sexuality of one gay man. Steward was also a dedicated diarist. His unpublished memoir – on which Spring draws heavily – offers insight into Steward’s well-drawn theories on the sexual mores of the day. All of this is delivered with Steward’s mordant wit, razor sharp self-reflexiveness and gently self-deprecating introspection. It is all filtered through an immensely well-read scholastic tradition. With incisive prowess gleaned from years in the academy, Steward dedicated his life to a brave and brazen self-examination without ever allowing the potential mental or emotional dangers inherent in such severe personal excavation to slow him down.

Secret Historian’s dramatis personae is a fabulous cross section of gay intelligentsia and cultural giants: his long-time friendship with Gertrude Stein and Alice Toklas, visitations with Thomas Mann and André Gide, interactions with Christopher Isherwood, Jean Cocteau, Tennessee Williams, Robert Mapplethorpe and Tom of Finland.

Contained in Steward’s Stud File are entries for Rock Hudson, Thornton Wilder, Lord Alfred Douglas and Rudolph Valentino. In addition to his sexual conquests – submissions – Steward amassed a collection of first edition books by important gay authors, hundreds of objets d’art, magazines, photographs and paintings.

Under the constant threat of detection and persecution in McCarthy-era America, Steward courted arrest. He hosted orgies, allowed himself to be filmed in a vigorous BDSM session for Kinsey’s archives, and carried a prodigious appetite for gay-for-pay hustlers. Steward felt a lifelong attraction to rough trade, subscribing to a hyper-masculine sexual ideal. He loved truck drivers, gang members, bikers and sailors. Conversely, Steward shunned most gay scenes and harboured a lifelong distrust and abhorrence of effeminacy.

Spring reveals Steward as a man who never achieved the recognition he warranted. Steward’s later years were plagued by depression, drug addiction and crippling loneliness. He was eventually left isolated in a Berkeley, California, coach-house, nearly drowning in at least three lifetimes’ worth of treasures and at least as much trash.

Ultimately, Steward’s life of sexual rapacity and abandon left him unfulfilled and, near the poignant and tragic end of Spring’s exhaustively detailed biography, Steward admits to his journal that the only thing he ever truly loved in his entire life was a dachshund named Fritz. In Steward’s elegiac and still unpublished memoir, he speaks often of cultivating an imperious sense of detachment as a shield against the inevitable ravages of old age.

What becomes of a person who dedicates his entire life to a pursuit of unfettered sex, even after time has stolen his youth and life’s many trials have robbed him of his belief in the redemptive power of beauty? Steward lived long enough to see the AIDS crisis change ideals of youth and beauty and kill many of his friends and former lovers.

Steward’s ennui is illustrated by the novelty doorbell he invented for his California bungalow. When rung, it chimed out the tune of an old drinking song, “De Brevitatae Vitae,” the lyrics of which translate to, “Let us rejoice, therefore, while we are young/After our pleasant youth and troublesome old age/The ground will have us.”

Had it not been for Spring, Steward’s doorbell may have served as his final knell. Thanks to Secret Historian, the examined life of Sam Steward has been granted posterity’s lovely veneer.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra