It’s been almost four weeks since the World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 a global pandemic. Ever since the announcement, the virus’ chokehold on the world has tightened more and more each day. Social gatherings have been dubbed a health and safety risk, physical distancing has become the new normal and I, like many people across the globe, find myself forcibly confined to my apartment, glued to the news and biting my nails as the apocalypse seems to unfold before me.

The days and weeks since the announcement have yawned into eons, and imagining a pandemic-free lifestyle feels like a luxury of the past—or perhaps one waiting for us in the distant future. But through our seemingly hellish reality, certain comforts have remained consistently and reliably warm and fuzzy. Schitt’s Creek, I’ve come to discover, is one of those comforts.

The CBC show, which ends its sixth and final season tonight, tells the story of the Rose family—a formerly filthy-rich clan of spoiled brats who, in a twist of economic fate, are forced to surrender all their assets and move to a small town indefinitely. At first, the four members of the Rose family are appalled by the quaint, proletarian lifestyle of Schitt’s Creek residents. But as the series progresses, each member of the family gradually embed themselves in the community they grow to call it home.

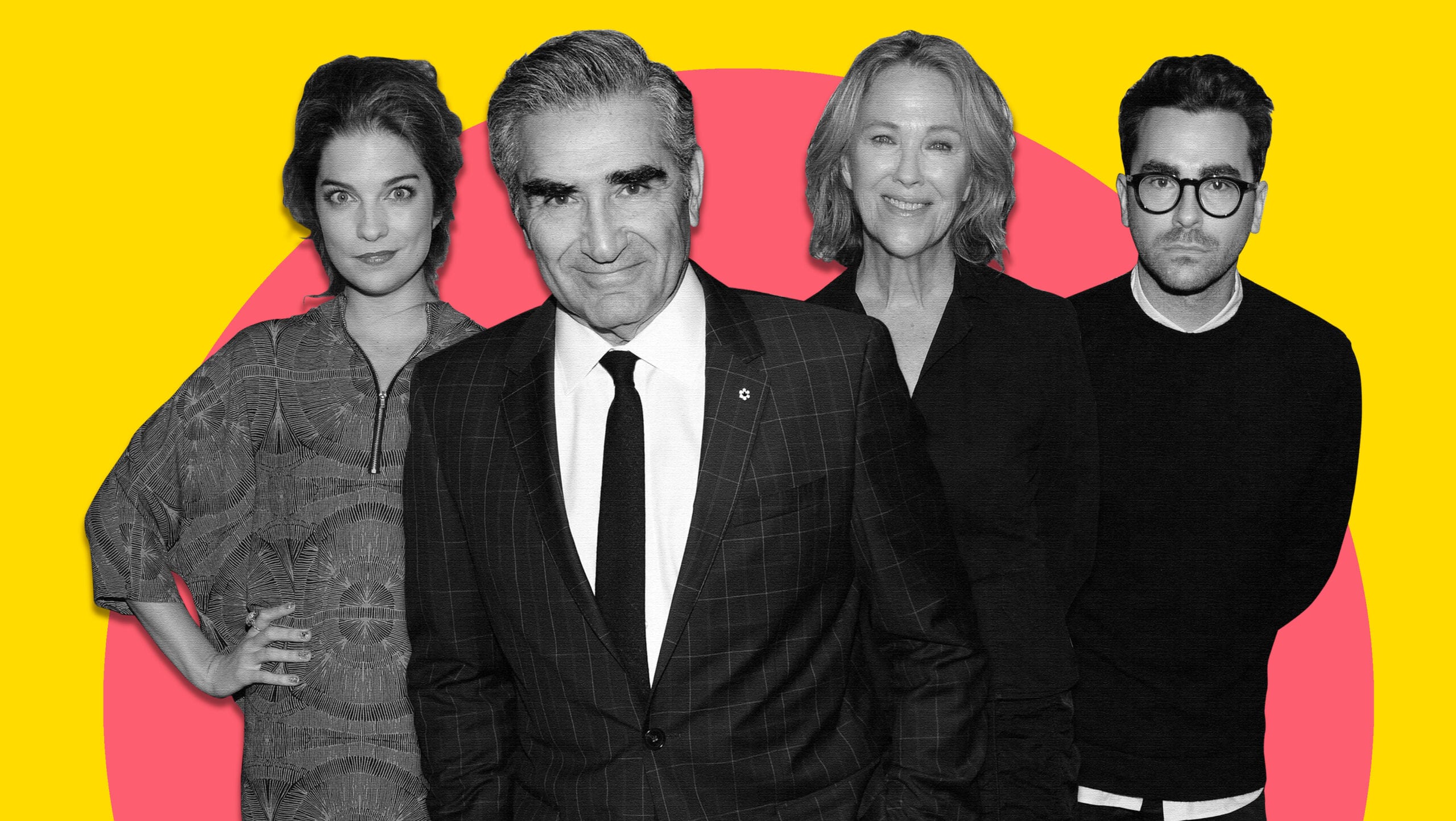

The appeal of Schitt’s Creek stems from a number of things: A commitment to low-stakes jokes in a television market that tends to reward the high-brow comedy of Fleabag or the exorbitant luxe of Game of Thrones, stellar comedic performances from all four main cast members (Dan Levy, Annie Murphy and comedy legends Eugene Levy and Catherine O’Hara) and a reputation for compelling story arcs that dependably culminate in happy endings.

“Through our seemingly hellish reality, certain comforts have remained consistently and reliably warm and fuzzy. ‘Schitt’s Creek,’ I’ve come to discover, is one of those comforts.”

Prior to COVID-19, I had a tepid relationship with Schitt’s Creek. I could flick it on and flick my brain off. It certainly got brownie points for being Canadian, and for heavily featuring (and celebrating) queer love. But now that the world and I are physically distancing, the little town of Schitt’s Creek has morphed into both a comforting haven in a time of crisis and an example of how to survive, no, thrive when you’re trapped somewhere against your will.

At the beginning of the series, the Rose family resents the fact that they are stuck in Schitt’s Creek—they view it as a prison. Their previous privilege makes them averse to any kind of discomfort, and the first couple seasons of the show essentially consist of the family continually trying—and failing—to escape what they see as imprisonment.

Eventually, they accept that Schitt’s Creek will be their home for the long haul. Once that acceptance sets in, unbridled joy emanates from the show like sweet heat from a smouldering fireplace.

“Now that the world and I are physically distancing, the little town of Schitt’s Creek has morphed into both a comforting haven in a time of crisis and an example of how to survive, no, thrive when you’re trapped somewhere against your will.”

The most obvious example of this is the relationship that blossoms between David (Dan Levy), the curmudgeonly son of the Rose clan, and Patrick (Noah Reid), his dashing fiancé. Their love story is classic: David’s got a tough exterior that only Patrick seems to be able to crack, and they gradually become warmly entwined as their story progresses. They have occasional spats, but their love for each other always triumphs over their petty conflicts. And they are just so cute together. One of the show’s best moments comes when Patrick, in a brazen declaration of undying love for his new beau, serenades David with a gorgeous acoustic version of Tina Turner’s “Simply the Best.” Watching that scene still gives me goosebumps.

It’s sublime storytelling, but it’s also quietly revolutionary. It seems so rare to have a story about a queer person that’s simultaneously genuinely joyful and fundamentally human. The conflicts faced by the characters in Schitt’s Creek are largely inconsequential, and the same is true of its queer characters. They don’t have convoluted, traumatic backstories, they aren’t punished for their queerness and they aren’t rejected by their families and loved ones as they tearfully emerge from the closet.

They’re just happy people with happy lives. That’s a paradigm that’s rarely afforded to queer folks. All too often, our stories end, begin or are defined by tragedy. The story of a queer person has always been a sad one, and true joy is not something that queer people are supposed to have—at least not on a sustainable basis.

Schitt’s Creek changed that. Through its meteoric rise from a minor Canadian television show on CBC, to becoming a hit in the U.S. (after it aired on Pop TV, an American-paid channel, which powered the show’s Emmy nominations) to gaining international popularity as a cult hit (fuelled by streaming service Netflix), the show has demonstrated that you can depict queerness as a normal, positive thing and still achieve mainstream glory.

That was something I took for granted before physical distancing. Before, I just kind of liked the show. I thought it was funny and cute, and a decent way to spend a half-hour. But now that I’m experiencing a sense of imprisonment myself, I’ve begun to cling to the show and its message that no situation is as dire as it seems as long as you lead with kindness, love and optimism. The Roses may be stuck, uncomfortable, and perhaps they’d rather be elsewhere. But they’ve got each other, they’ve got a home, and through time and experience, they realize that that’s more than enough.

Schitt’s Creek certainly isn’t perfect. People have pointed out the overwhelming whiteness of the show’s cast and how it’s not the most dynamically written show: It doesn’t really tackle any major social issues, its plotlines and character arcs are predictable, its premise (rich family goes broke) is derivative and much of its humour stems from its characters’ stubborn inability to evolve beyond their worst traits. While reviewing the show’s pilot for The New York Times, television critic Mike Hale called Schitt’s Creek, “a show that’s drab and underwritten, with potentially amusing (if familiar) situations that never build to more than a chuckle or a nod of recognition.” But, in times like these, maybe simplicity and predictability aren’t so sinful.

As the world seems to collapse outside my window, and the future looks uncertain at best and bleak at worst, at least one thing has remained constant. Like clockwork, 22 minutes of delightful escapism appear on my PVR on a weekly basis in the form of Schitt’s Creek. That routine, like every other, is drawing to a close. But if Schitt’s Creek taught me anything, it’s that beautiful beginnings often come disguised as devastating goodbyes.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra