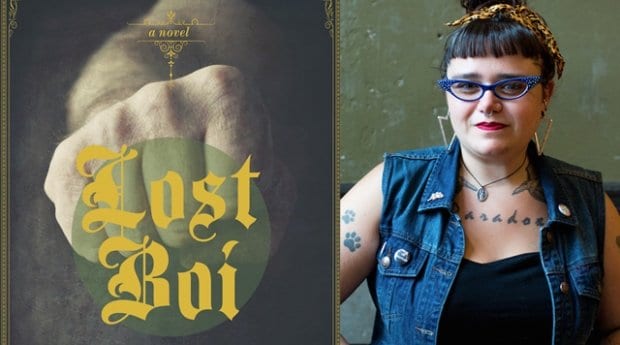

Imagine Neverland as a burned down warehouse ruled over by a trans-Dom-Pan and populated by his tribe of runaway lost bois. Throw in some sex-working mermaids, pigeon fairies and a leather daddy Captain Hook who redefines what it means to “fly,” and you have Lost Boi — a raw, radical and contemporary adaptation of J M Barrie’s Peter Pan stories from queer punk author and trans activist Sassafras Lowrey.

Beyond the transgressive pleasure found in Lost Boi’s gender-fucking and in the brazen placement of beloved literary characters into the world of queer kink and leather culture, there is also insight into the myriad ways in which marginalized folk seek to forge familial ties and create community.

Daily Xtra: There seems to be a certain amount of autobiography in Lost Boi. How much of your own past informs the narrative?

Sassafras Lowrey: My life experiences and my community have all informed my fiction writing. I am most inspired to write queer books for queer readers, and so I definitely take inspiration from my own life and various queer communities that I have called home. Particularly, the themes of growing up, or not, were heavily inspired not only by my life but from watching those same cost/benefit analysis and debates taking place amongst queers.

One of the recurring metaphors in the book seems to relate to the idea of a gentrification or mainstreaming of queer culture.

Definitely. I think those forces are real and present in the lives of most queer folks and we each, in our own ways, make decisions about how we allow our queerness to become mainstream. For the characters of Lost Boi, those tensions and stakes are heightened, but the inspiration for including themes of mainstreaming queer culture came from the complicated decisions I and others in my community have navigated regarding stability, growing up, jobs, education, etc.

Is there a pedagogical aspect to the book? Are you hoping to introduce young queers to the possibilities of leather culture and more radical forms of sexuality?

I see the infusion of leather into the novel as less about indoctrination, and more about representation. Leather culture and dynamics have been integral to my own life, and the queer culture that has been my home since my youth. I want to create books that depict these possibilities so that queer readers can see themselves, relationships and communities reflected on the page.

Lost Boi resists simplistic moralizing, and even ends with a picture of two very different, yet still functional, life paths. Can you speak to the importance of queers finding their tribe/family?

I believe that the most important thing queers can do is to build our own families. The idea of the chosen family plays out within Lost Boi in a few different configurations and with varying permanence. Connected to those families are the diverging life paths that the characters are grappling with and trying to make sense of. While writing Lost Boi, I was really committed to exploring the cultural understanding of the “Peter Pan syndrome” that is considered common within some aspects of queer culture, as well as queer cultural struggles with the idea of “growing up,” that queers of my generation are very focused on right now, and how that can intersect with relationship dynamics, stability and career goals. I wanted to explore these themes without judgment, because there are so many ways to live queerly.

Lost Boi is published by Arsenal Pulp Press and is available at

Glad Day Bookshop, 598 Yonge St, Toronto

gladdaybookshop.com

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra