Edmund White thinks a lot of biographies take a moralistic stance.

Following the recent deaths of Christopher Hitchens in December of 2011 and Susan Sontag in the same month in 2004, and with the possible exception of Gore Vidal, Edmund White is a worthy nomination for the mantle of preeminent essayist in American letters.

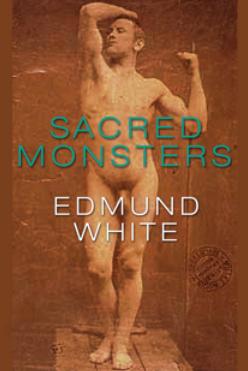

The prolific author of fiction, non-fiction and theatre has recently released a new collection of essays called Sacred Monsters. The title comes from the French term monstre sacré, which, as White explains in the book’s introduction, refers to “a venerable or popular celebrity so well known that he or she is above criticism, a legend who despite eccentricities or faults cannot be measured by ordinary standards.”

White takes a biographical approach to the collection’s 22 portraits of artists ranging from Rodin to Proust, Isherwood, Hockney, Forster, Nabokov and Capote. White explains that for him, “the evaluation of an artistic career can best be examined through biography; only by seeing a writer or painter among his contemporaries can we judge how original he or she was.”

I spoke to White about some of his monsters by phone from his annual retreat in Key West, where he has been vacationing since 1979. White — who once described biography as “the judgment of little people avenging themselves on the great” — makes the case that what often renders biography “so middle class” is many authors’ moralistic approach to their subjects.

White feels that “an awful lot of biography raps the subject over the knuckles for being adulterers or being bad fathers.” He rejects this rarified approach to chronicling the lives of artists. “First of all,” he explains, “if you did biographies of the great butchers or bakers of the world they would be just as reprehensible . . . secondly it’s so irrelevant to their art.” According to White, “a lot of biographers, in order to have a point of view that connects with the average reader, take a moralistic stance.”

The profiles in Sacred Monsters are culled largely from The New York Review of Books. White chose his subjects out of both a personal fascination and “to draw attention” to artists — most of them gay, all of them queer — who have intrigued or inspired him as a writer. “We live in a funny age,” laments White, “where terrible books are exalted [while] so many masterpieces of the recent past are forgotten.”

White tells me he tries “not to write about somebody I don’t admire — at least for their work.”

However, his stylish portraits transcend the insipidness of mere hagiography. In their most sublime moments, they attain a deeply personal subjectivity that reveals profound insight and rewards multiple readings.

Although he has often been criticized for injecting himself into his biographies of Genet, Proust and Rimbaud, as well as into his essays, it is this personal touch that endows White’s work with its unique disposition. “I was brought up in an era where you weren’t supposed to write about yourself,” White says. “Then after I became what the French call a signataire, editors were saying, ‘Yes, but what do you think about this?’ And then that became a new way of writing for me.”

In his essay on Nabokov, White quotes from Adorno’s Minima Moralia: “The universality of beauty can communicate itself to the subject in no other way than in obsession with the particular.” White’s use of his own life in his non-fiction functions in the same way, by wringing universality out of the personal.

In the most recent issue of The Gay and Lesbian Review, novelist Andrew Holleran — a former member of The Violet Quill, a queer literary salon that also included White — posits that “Biographies are like mummies: in exchange for permanence, the vital fluids are removed.”

With Sacred Monsters, White disproves his old friend and colleague by rendering biographical portraits of fascinating queer artists that retain a healthy pulse.

The Deets:

Sacred Monsters

By Edmund White

Magnus Books

$24.95

Below is a video interview that Edmund White did with Xtra in 2009.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra