As I contact Ross Higgins at the Quebec Gay and Lesbian Archives (AGQ) about the New York exhibit of late Montreal artist Alan B Stone, my timing is off: on March 30, Montreal saw the passing of another early pioneer in homoerotic art, Peter Flinsch.

“I am still a bit in shock,” says Higgins, who has not only specialized in Flinsch’s work, but has spearheaded an historic renaissance of the artist’s work. Higgins’ collection and commentary on Flinsch is published in Arsenal Pulp Press’s Peter Flinsch: The Body in Question. (read more about the life and work of Peter Flinsch)

“Flinsch is an extremely productive artist of many styles,” Higgins said just last year. “He has a lot of very developed drawings of life in the Montreal village after 1980, with this capacity to memorize faces and cruising, all in sardonic and comic tones that simply can’t be done in photography…. Flinsch is able to express his idea of a man and of masculinity in just a few simple lines.”

While contemplating Flinsch’s memorial and continuing research into Flinsch’s life and career, Higgins and I take the time to chat about the New York exhibit of another Montreal pioneer in homoerotic history: Alan B Stone. Entitled Alan B Stone and the Senses of Place, the exhibit runs at New York City’s International Center of Photography (ICP) until May 9.

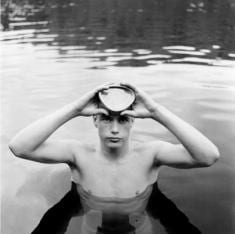

Stone, a commercial photographer whose 1950s and early 1960s work included some often risky beefcake pictorials, was an ambitious Montrealer who never officially came out. The artist shuffled physique work with travel photography and stories, as well as some of the best shots of Montreal in the era.

Higgins first met Stone alongside Concordia professor and collector Thomas Waugh, when the pair interviewed Stone on the beefcake nature of his imagery.

“He was someone who came across as very much commercial-oriented,” affirms Higgins, “and a bit gruff. But we hit it off from the beginning, and I think he was secretly delighted to have that side of his work rediscovered.”

Stone’s work, not unlike that of Flinsch, came from an era of extreme religious oppression in Quebec, when whisking off to Île Ste-Hélène to shoot hunky bodybuilders was as secret as where you stashed your Playboy magazines (a magazine Higgins laughs was then available only in Ontario). After hardcore work and gay liberation arrived, and entrepreneurs like Weider changed the face of the bodybuilding and fitness magazine industry, Stone veered in a mainstream direction, particularly after causing a scandal photographing noted Montreal bodybuilder and gym owner Billy Hill.

“Stone didn’t do nude or sex photography,” affirms Higgins, “so the photos of Hill considered to be obscene were seized and returned. But that work in a way was all undercover, simply because he belonged to a generation that lived by discretion.”

Higgins and Waugh brought Stone’s work to life with a major exhibit in 1992 via the Archives. Held the same year as the 350th anniversary of Montreal, Stone saw the exhibit shortly before his passing the same year. He was fully aware of the homoerotic forthcomings in his work, and their place within a queer community of appreciative viewers. A documentary on Stone, entitled Eye on the Guy: Alan B Stone and the Age of Beefcake, was more recently released.

Curator David Deitcher provides us with another post-mortem accomplishment for Stone at the ICP. A New Yorker with a passion for his native Montreal, Deitcher discovered Stone’s work thanks to Higgins, Waugh and the Archives, and has already created a similar exhibit on Stone in San Francisco. The current exhibit, which incorporates a broad spectrum of Stone’s images, allows the artist to remind us how photographs evoke our sense of time, place and memory.

After archiving more than 50,000 or more negatives on Stone as a permanent collection at the AGQ, Higgins is hoping Deitcher’s exhibit will make a stop in Montreal.

“He devoted his life to photographing the male form,” describes Higgins. “You see the posing straps, the flexing, the old newsstands, the repeated iconography of the same bathing suits on different guys. But he was a bit of an inventor, and very big on travel ideas…. it was only when his mother agreed to transfer his work to the Archives that we discovered his own love of Montreal — subjects like the Lachine Canal, the Old Port, and old sporting events. Many people have said they are some of the best out there.”

Unlike Flinsch, Higgins admits it was only upon Stone’s death that so much more of him was revealed. Considering the vast collection of materials of these prolific artists, says Higgins, it won’t be long before we discover more. Until then, we’re fortunate the AGQ will preserve them for years to come.

For more on Stone’s NYC exhibit, visit icp.org. Meanwhile, a memorial and tribute page to Peter Flinsch has been set up at peterflinsch.com for comments. For information on the AGQ collections and upcoming events in Montreal, visit agq.qc.ca.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra