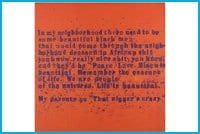

STENCIL ME IN. Glenn Ligon's Beautiful Black Men from 1995, a reworking of Richard Pryor skits

I first saw Glenn Ligon’s work in 1998 at a Power Plant show entitled Changing Spaces. His pieces in the Skin Tight series were mesmerizing and shockingly powerful. Skin Tight used text from film, rap lyrics and advertisements transferred onto heavy-weight punching bags, exploring the idea of violence and white society’s fear of black masculinity. That initiation into the world of Ligon truly moved me, and provoked an avid interest in his progress as an artist. Now, seven years later, the Power Plant is exhibiting Glenn Ligon: Some Changes, a major survey of more than 15 years of his work. While the survey does not include the Skin Tight pieces, the exhibition shows that Ligon’s passion remains undimmed.

Glenn Ligon: Some Changes marks both the profound lack of progress in race relations in the US as well as the possibility of change. Every piece in this exhibition in some way contributes to the analysis and critique of the African-American experience. Many pieces are dark, both aesthetically and intellectually, as words, shapes and dual messages are explored predominately on a large scale and in black and white. While his intentions are deeply rooted in exploring black masculinity, the context of his work becomes part of the larger dialogue of race in George Dubya’s America. Ligon’s work

is a fierce attack on oppression.

A series of large-scale black and white silkscreen prints (approximately 10 feet by four feet) have heavily inked surfaces with black fists raised in solidarity and protest. A white poster towers above them; we cannot see if there is text on it. To the right of the prints is the imposing Washington Monument. The image has been taken directly from a newspaper clipping of the 1995 Million Man March in Washington, DC. The image exists beyond time because of the pixilation and quality of the print; it could be from a 1960s civil rights march or an antiwar demonstration last year.

The series is spooky. Oppression and hatred of African-Americans not only persists but does so with a twist – now, anyone who is a shade of brown can be targeted

as violent perpetrator or terrorist. These pieces evoke a double-

barrelled shot of hope of unification in the face of oppression and hopeless invisibility.

In North America, fear of black masculinity is never far from sex. But Ligon makes his gay identity almost commonplace in Annotations, a scrapbook-style family album available both as a web-based project and in book format. Photographs of new babies, special moments and portraits are intermingled with homoerotic images and porn. An image of a man with an erection sitting on a bed looking through a book is juxtaposed with a family portrait. Do we reduce gayness to its lurid, sexual component? Or is sex all that lurid? Ligon’s response to such questions is funny, subtle.

In a series from 1992 Ligon stencils “I do not always feel colored” on three different colour combinations to examine the shifting experience of race.

One piece is black text on white canvas, another is black text on black canvas and the other is cream text on white with X’s through it. Metaphorically, this series challenges us to recognize the inescapable interrelationship between an individual’s personal struggle and social attitudes and forces. At times omnipresent, blackness can also result in invisibility.

Ligon’s approach often quivers with dense humour and rage. Small “Wanted” posters grace the beginning of the exhibition, his versions of old posters of runaway slaves. Rather than using archived text, Ligon describes himself. “Ran away, Glenn. Medium height, Black rimmed glasses that are somewhat conservative. Very warm, sincere, mild mannered and giggles often.” What is jarring is that Ligon not only places himself as oppressed seeking freedom but the descriptions are accurate enough to spot him in a crowd. Because of these posters, I found Ligon in the gallery. In this allegory of the hunted, Ligon made me, art critic, into pursuer.

Material and media play an enormous role in Ligon’s critique, and in two different series he applies these aspects to investigate the economy or commerce of black masculinity. Several pieces in the exhibition use coal dust mixed with adherent to form text on canvas. The chunky masses of text are often illegible but appear to be glittering black jewels swimming within the parameters of the canvas. His use of coal dust signals the profound, often tragic history of hard labour in the deep South. Coal mining left many women widows and children orphaned due to the high probability of occupational disease such as Black Lung. In an obscure way this particular series marries a racial divide between blacks and whites in the South; the material becomes a metaphor for poverty-stricken labourers working together to warm the houses of the wealthy.

In Negro Sunshine, a larger-than-life neon sculpture, Ligon also points to the reality of poverty among wealth. In a bubbly font reminiscent of a holiday pamphlet the words “Negro Sunshine” stretch across a large wall. The sculpture illuminates with enough creamy light to catch attention yet is has a gloomy glow, creating a pensive, ominous space. Any thought of this piece motioning toward a holiday or vacation is nullified by its evocation of a hallway in project housing or the nightglow of dimmed prison lights.

The scope of African-American artists exploring black identity and history, like Faith Ringold, Kerry James Marshell and Kara Walker (among many others), abound with distinctive reflections and reactions. But what ultimately differentiates Ligon from his contemporaries is that, for Ligon, artist intent trumps skill. Techniques like stencilling or marking up children’s colouring books are fairly easy to apply and manipulate. But Ligon labours over the concepts, building up layers of meaning.

His conceptual emphasis is showcased in two, small, lavishly adorned rooms containing the most colourful pieces in the exhibition.

Adjacent to Negro Sunshine are images from kids’ colouring books that have been filled in by children, then enlarged. The effect of childish blocking of space and colour are playful and fun, but because the subjects are black power motifs such as Harriet Tubman, the pieces become more than childish marks, forming arresting symbolism. Ligon’s painted mural of a rainbow sunburst uses the similar scratchy hand of a child. The sunburst centre is a now ubiquitous image of Malcolm X, a leader whose intensity and penetrating stare is shadowed by whimsical colours and gestural lines. The black power message explodes with light-hearted humour.

Ligon’s Richard Pryor paintings harbour the profound rage and truth of the black male experience. The psychedelic colours of these pieces ignite the room with the brightest of reds, yellows, greens and mauves. Text is loosely stencilled over shimmering canvas, often in oppositional colours, like green over red. The result is Warholesque. But instead of siphoning out meaning as Warhol maintained, Ligon instills new layers of meaning to snippets of Richard Pryor’s stand-up comedy. The hyper-coloured text is unabashed. The stencilled words seem earth-shaking in today’s neoconservatism, brash, dirty and powerful in their race commentary. “Nigger” is splashed across multiple canvases, and one can’t help but wonder how the politically correct contingent will fare with the word staring them in the face. On one canvas the text reads, “Niggers be holding them dicks too…. White people go, ‘Why you guys hold your thing?’ Say ‘You done took everything else motherfucker.'”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra