Credit: (Molleindustria)

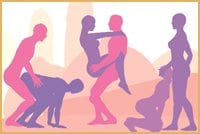

Picture a setting where clouds in the shape of puffy cocks and scrota populate the sky. The pink-hued landscape below is a blend of gently pulsing, hard-nippled breasts and even more cocks — erect — rocking in an apparent breeze.

In the foreground, two human-like silhouettes, bodies lightly heaving, square off on opposite sides of these subliminally sensual surroundings.

Suddenly a penis sprouts on the body of one figure who leaps with aggressive stealth towards figure two — a woman. Maybe.

Figure one makes a final ecstatic lunge for figure two who morphs into… a man (maybe), crouching on all-fours, butt in the air, waiting to receive.

Figure two has pulled the ultimate gender-fuck, not to mention, sex and sexual orientation manoeuvre.

But not quite.

Figure one backs up and regroups. So to speak.

The penis and its hard-on disappear leaving figure one’s gender indeterminate. Dropping to a crouch as well, figure one moves towards figure two’s ass — now at mouth-level — and goes to work.

The sexual play sounds like a cross between screeching monkeys and creaking hinges.

Figure two climaxes, the orgasm unfolds like someone dragged a digital needle across digital vinyl.

Welcome to Queer Power, your have-sex-anyhow-with-any-gender (or no gender) video game oyster.

The game was among five juried submissions in the installation category of the ninth installment of Signal and Noise, a Vancouver-based festival of avant-garde, interdisciplinary art hosted by Vivo Media Arts Centre, Apr 17-19.

Queer Power, which invites players to fuck-and-give-pleasure instead of fight-and-eliminate, stands the traditional video game on its head in its look, characters, content, goals, and even its audience.

It’s the brainchild of the video game collective Molleindustria, which develops and promotes video games that challenge mainstream commercial gaming, as evidenced in the names of some of its other projects — Faith Fighter (“religious hate has never been so much fun”), Operation Pedopriest (“establish a code of silence and hide the scandal until the media attention moves elsewhere”), and Where Next (which encourages those tired of betting on the Nasdaq and sports matches to bet on where the next terrorist attack will take place).

The primary creative force behind Queer Power, Paolo Pedercini, says his Signal and Noise entry is a parody of blood-and-gore fighting games like Mortal Kombat, popularized in the early ’90s, that endorse a Western militaristic perspective.

“If you check the many simulation-like games, they are mainly on the side of the mainstream idea, of course,” observes Pedercini, noting what he calls “the lack of alternative voices” in the gaming field.

“You can find a lot of movies that can be critical to the establishment, and you can find the same for books and theatre plays and so on, but you cannot find anything similar in the video game field. So that was our intention,” he explains.

“Basically, everything in the [Queer Power] game is reversed. Instead of sucking energy, or stealing energy from your opponent, you’re providing pleasure.”

Queer Power is also loosely inspired by queer theory and particularly the work of gender theorist Judith Butler, author of Gender Trouble, adds Pedercini, who says the intention was to unpack gender as a cultural construct, as something that can be freely chosen and changed.

“We thought [the game] was a relatively simple way to summarize the idea, this comprehensive idea about all the sexual deviation you can have from the [binary] norm.”

It is also about putting desire at the centre of people’s focus. “You’re the player,” he points out. “You can manage your desires; you can operate according to your desires.”

Pedercini likens Queer Power, developed in 2005, to “a formal experiment,” revealing that he thought people would hate it for being pointless and not playable. He himself says he’s “not extremely happy” with it.

Part of his unhappiness stems from his inability to create or find more androgynous figures instead of the stereotypical-looking males and female forms. The result, he says, is that some players don’t get the message of gender and sexual identity subversion.

“Few people get the message because the characters themselves are kind of straight,” he complains, noting it was a “forced choice.”

But media artist and festival juror Brady Marks, who brought Queer Power to the attention of Signal and Noise organizers, says she was drawn to Pedercini’s “hilarious and fun” reworking of the fighting game format, and infusing it with a “let’s fuck” attitude.

Queer Power also resonated with Marks on a more personal level.

“I guess when I first encountered it, I was exploring my own gender identity. Then it became this ludicrous space where anything went — a free-form exploration,” explains Marks who is a trans woman.

“I do think also you can’t think of it as serious. It’s not really about sex per se because it’s very detached from the body but it’s really about media and representations of conflict and sex.”

When the festival theme Media Intercourse was broached, Marks says Queer Power seemed like a perfect fit.

“Basically you have different ideas around media, whether that’s film, video, sculpture, installation, internet — all those media. And then the idea of intercourse, which can be taken more broadly so, for example, mixing sex, body fluidity, hybridization — all those themes. So the festival then is a place where these possible linkups can happen,” Marks concludes.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra