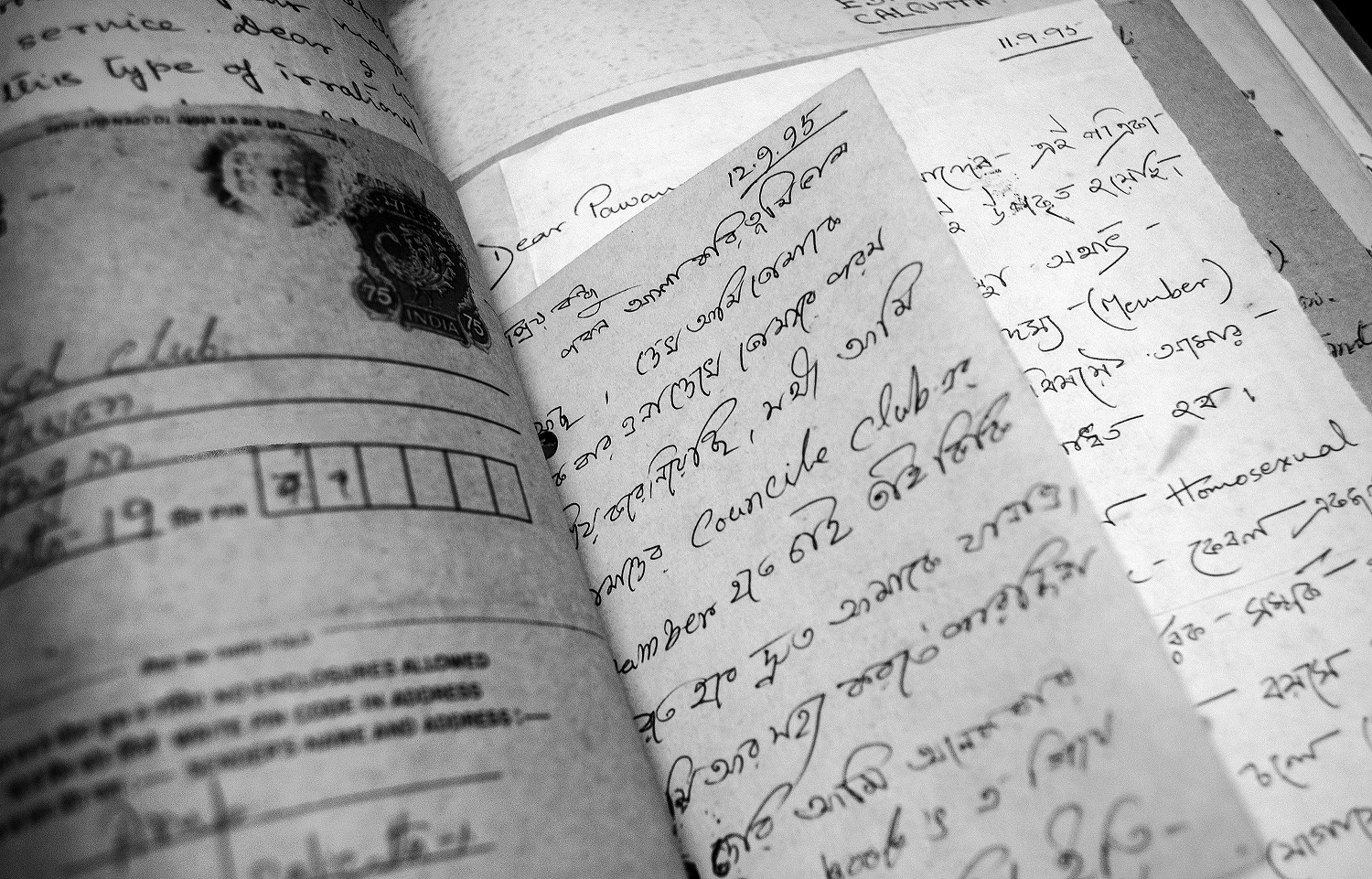

“The files don’t simply contain letters, but greeting cards and postcards as well. These files are an archive of memories of desires, of testimonies of friendship, often forgotten and erased. As one opens the files and flips from one letter to another, one is overwhelmed by the voices speaking with each other; voices desperate to be heard; voices that refused to remain silent and yet voices shut inside a file.”

This is an extract from an article Letters of Desire, written in 2013 by Professor Zaid Al Baset, a teacher of sociology at St. Xavier’s College in Kolkata. The article was published in Varta, a webzine published by Kolkata-based gender and sexuality non-profit Varta Trust that I co-founded in 2012 with a group of activists, researchers, artists and lawyers.

Baset was writing for a series on queer archiving in India, intending, as it was introduced, “to create an archive of the queer movement in Bengal and India. It is not a chronological narrative of the movement, rather anecdotal histories capturing the little voices that are often lost in general historical accounts—to begin with, voices from thousands of letters received by Counsel Club, one of India’s earliest queer support groups, in the period 1993 to 2002.”

At one time, a fellow researcher had commented that the letters would be only of passing interest and mostly only to academics. The readers’ response to the series in Varta, though appreciative, seemed to confirm the researcher’s point. But the importance of recording the “little voices” that are often lost in dominant historical narratives, and the potential of queer archives in general to serve the cause of social justice, was to be driven home much more forcefully not many years later.

In September 2018, when the Supreme Court of India irreversibly struck down Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code, a 25-year-old battle for the decriminalization of queer people came to an end. The media all over the country had a field day reporting the development with colourful headlines. Some sections of the media focussed on the petitioners behind the verdict, “The famous and fearless five who convinced SC” as described by The Times of India, India’s leading English newspaper. “Meet the 5 petitioners who challenged Section 377” exclaimed Yourstory.com.

Who were these “famous and fearless five”? They included a renowned choreographer, a former journalist, a businesswoman, a hotelier and architectural restorer and a celebrity chef, all five from well-to-do socioeconomic backgrounds in urban India who claimed that Section 377 violated their right to life and personal liberty guaranteed by the Constitution. In their petition, they described themselves as “highly accomplished” personalities. A mix of factors, including the timing of the petition, led to the Supreme Court’s verdict being named Navtej Singh Johar & Others vs. Union of India Ministry of Law and Justice, that is, after the lead petitioner, the choreographer.

When the stories applauding the courage of the five petitioners broke out, many queer activists, community peer leaders and even lawyers engaged in long-running sociolegal campaigns against Section 377 asked, “But who are they?” The question was not as much about their identities as it was about what role they had played in the battle against Section 377. The issue uppermost on many minds was what about the other petitioners, individual and organizational, who had together fought the law—with far fewer social privileges and at great personal cost—both in and outside the courts for decades?

To put things in perspective, the “highly accomplished” set filed their petition only in 2016. Before this, they were not known to have participated in or contributed to the community struggles for decriminalization. Compare this to New Delhi–based activist group AIDS Bhedbhav Virodhi Andolan, which first filed a petition against Section 377 in 1994 (this petition was dismissed by the court in the early 2000s), and sexual health non-profit Naz Foundation (India) Trust, also based in New Delhi, whose 2001 petition was the one that led to the 2018 verdict through a long chain of events that played out in the Delhi High Court and Supreme Court. Both agencies had long histories of fighting for the social justice and public health concerns of marginalized social sections, including queer communities.

The “highly accomplished” petitioners were not even among the first queer individuals who stuck their necks out in court as parties affected by Section 377. In 2006, civil society collective Voices Against 377 became co-petitioners to Naz Foundation and filed six individual affidavits in the Delhi High Court, making it the first time queer individuals directly joined the legal battle in court. Among the dozens of petitions filed against Section 377 through the years by queer individuals, their parents, teachers and mental health professionals, there was one by Lucknow-based queer activist Arif Jafar. He was arrested in a case of abetment of Section 377 in 2001, simply because of his work around sexual health outreach among gay men and trans women in public places. He was incarcerated for 54 days before managing to obtain bail with the help of human rights lawyers. His arrest catalyzed the Naz Foundation’s petition against Section 377. Very little or none of these facts grabbed the commercial media’s attention in 2018.

As someone personally involved in queer activism since the early 1990s, and in the last decade also archiving the work and lives of queer people for posterity, I see not just a class bias or lack of professionalism in the media stories highlighting primarily the “famous and fearless five.” When I look back at the stories of grit exhibited by trans and queer community members across India against police violence (with or without Section 377 in the picture), what also comes across is careless or deliberate erasure of India’s recent queer histories by dominant social groups, many among the queer communities themselves.

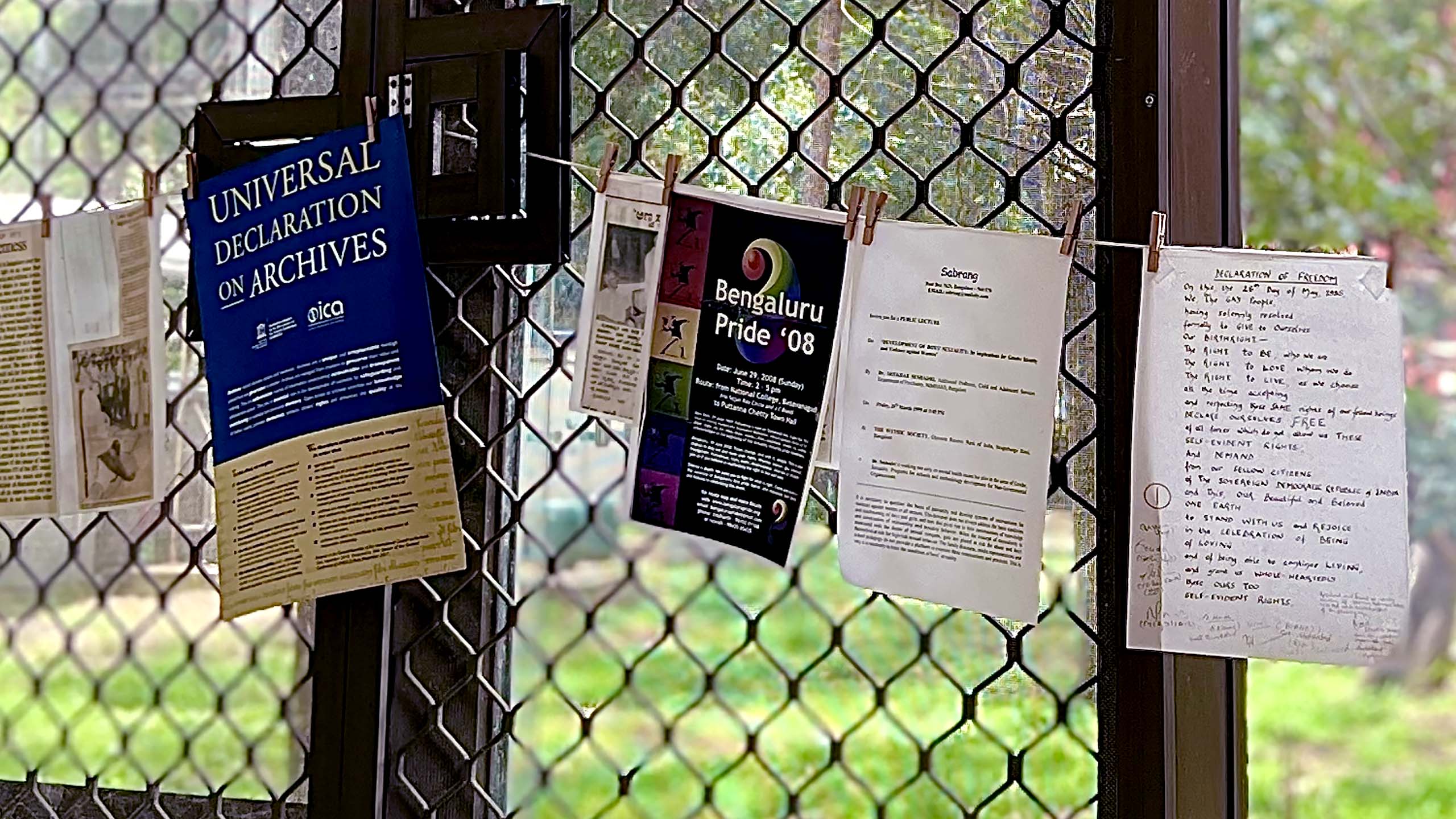

Credit: QAMRA Archival Project

Fortunately, such a slide into oblivion is being arrested by initiatives like the QAMRA Archival Project at National Law School of India University (NLSIU) in Bangalore. India’s first effort dedicated to a systematic archiving of queer histories, QAMRA stands for Queer Archive for Memory, Reflection and Activism. The groundwork for setting up QAMRA started in 2013 with a conference that brought together queer activists and researchers from across India. A more formal start with the name QAMRA and a team of people deeply engaged in queer activism, media, law, history, anthropology and education happened in 2017.

At the helm of the affairs of QAMRA is co-founder and independent filmmaker T. Jayashree, whose work focuses on the intersections between gender, sexuality, law and public health. Her filmography includes landmark documentaries like Many People Many Desires (2007), an in-depth narrative of the sociolegal realities of queer people in Bangalore and more generally India.

“QAMRA’s key objective is to gather material on Indian queer histories that will be lost soon—material that shows how it was for queer people 20 or 30 years ago,” Jayashree says. Indeed, preservation of archival material has not been the strong point of most queer support groups in India. Lack of resources could be one reason. Preservation may also have taken a back seat because the priority was to fight the more immediate social injustices. But if no efforts are made as queer activists and community voices from Generation X pass away, there will be little institutional or collective memory left of the recent queer histories of India.

“Equally important is the emotional experience of a hands-on encounter with the historical material and appreciating the effort put into its preservation.”

There is also the reality of digital media. Two to three decades is not a long time in history. But, given the digital and online lives that many people lead now, the analog realities of even the 1990s and 1980s may seem distant and possibly irrelevant to millennials and Gen Z. QAMRA has the potential to address this gap in understanding. As Ammel Sharon, the project director and lead archivist of QAMRA says, “QAMRA is in many ways a house of memories for the newer generations.”

QAMRA’s location in a university seems apt because students constitute an important audience for the archives. Jayashree also emphasizes that the original material—legal documents, charters, reports, journals, media clippings, letters, posters, leaflets, photographs, audiovisual material and a host of ephemera—should be easily accessible. She argues that though digitization is important for preservation and facilitating wider access across geographies, people who are interested in queer histories should actually visit the archives and see things first-hand. First of all, not all the material in QAMRA is or will be digitized. Equally important is the emotional experience of a hands-on encounter with the historical material and appreciating the effort put into its preservation.

One of the most exciting collections in QAMRA’s growing repository is the “Section 377 IPC Collection,” a set of court documents, research and other writings, ephemera, newspaper articles and videos of interviews with queer community members and allies. The videos have been shot by Jayashree herself over the years, and the interviewees include several individual intervenors involved in the legal battles against Section 377. One such interviewee is queer activist and faculty member at the Indian Institute for Human Settlements, Gautam Bhan, who filed one of the individual affidavits as part of the Voices Against 377 petition in 2006. In the video, Bhan reads out his affidavit and explains that he was fighting for queer people’s right to life with dignity. He came out as gay in a court of law at a time when doing so could have invited prosecution under the very law he was fighting against. In contrast, when the famous and fearless five filed their petition 10 years later, the tide already seemed to be turning in favour of decriminalization of queer people.

Interviews like Bhan’s in the QAMRA archives are evidence that the media stories of 2018 presented a one-sided picture of who had been fearless in the drawn-out battle against Section 377.

As a queer activist, I have been no stranger to the questionable approaches adopted by the commercial media in talking about queer issues. The decriminalization verdict of 2018 led to a spate of phone calls from journalists, including senior reporters from leading newspapers and TV channels. Several of them tried to put words in my mouth by wanting me to talk about the “inevitability” of marriage equality in India now that the decriminalization of queer people was done and dusted. This seemed like an attempt to set a narrative around queer marriages because it would be sensational in a country known to be crazy about big fat weddings where only a man and woman can tie the knot, upholding the heterosexual ideals of marriage, reproduction and family-making.

Many of us in the queer movement, on the other hand, talk about issues crucial for the sheer survival and well-being of queer people—access to educational and livelihood opportunities, mental and sexual health and social security among others. We also talk about the right to live out a relationship of one’s choice, and cohabitation. None of these require marriage, and marriage does not guarantee most of these. We argue that the next big battle for queer people in India should be around legislation to ensure non-discrimination in all spheres of life.

Advocating for such legislation will require extensive evidence, not just current, but also extending into the past, to show the history of how queer people have been wronged through the years. As an archivist, my work is in large measure about preserving, researching and disseminating such histories. In 2019, with guidance from QAMRA and resources from Varta Trust, I systematized the preservation of queer archival material in my possession for many years. I began cataloguing and digitizing a large archival collection related to the Kolkata-based Counsel Club. One of India’s earliest queer support groups, it functioned from 1993 to 2002. I was a founder and part of this group almost till the end.

Credit: Courtesy of Pawan Dhall and Seagull Books

Among various materials, the collection includes between 2,500 and 3,000 letters, greeting cards and emails from the years when the internet had just arrived in India. It also includes copies of Pravartak, Counsel Club’s house journal; other queer-themed journals; media clippings and extensive records of the group’s community mobilization activities. The letters were written to the group by queer people, activists, researchers and journalists from all over India and abroad. The letter-writers were diverse in terms of age, gender, sexuality, language, occupation, religion and location, though a majority would have been from the middle classes. Many of the queer letter-writers were looking to find friends and sexual partners; several wanted to share stories of loneliness, oppression and their struggles around living out queer relationships; some were looking for health and legal support; a few were even looking for career advice.

Samar (name changed), 22, wrote from a Kolkata suburb in September 1994: “I have heard of your organization from a friend of mine. I am interested in joining your organization.… I am now doing my master’s degree. As you might have guessed, I am gay, although I have not yet had any sexual experience. In this country, and especially in West Bengal, homosexuality is a social taboo and homosexuals are more or less social outcasts. So, I cannot confide in anyone and am leading a very lonely life.”

“Especially in West Bengal, homosexuality is a social taboo and homosexuals are more or less social outcasts. So, I cannot confide in anyone and am leading a very lonely life.”

The archival records show that just two letters were received from Samar and replied to over two months. In his second letter, Samar wrote that he was very happy that he had received a reply from Counsel Club. He was changing houses and said that he would be in touch after settling in at the new house. But there were no further letters from Samar. If alive, he would be around 50 today. His whereabouts may be unknown, but an imprint of his loneliness survives.

Today, letters and greeting cards are all but forgotten in many circles. But these missives from not so long ago were among the first expressions of queer aspirations in India, many of which remain unfulfilled. Samar’s reality of fear and isolation would not be alien to many queer people in today’s India as well, notwithstanding the proliferation of queer support forums across the country and increasingly on social media.

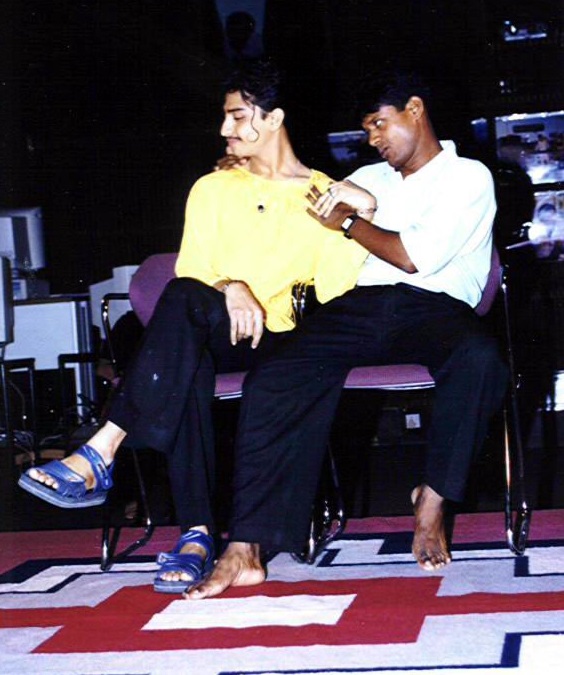

Another concern that has not gone away is HIV/AIDS. In 2001, Counsel Club and a sibling NGO called Integration Society scripted and produced Koti Ki Atma, a comic skit on HIV/AIDS awareness for community members. “Koti” is an identity term common in South Asia for feminine males who often play a receptive role in sex with other males, and Koti Ki Atma translates as “the spirit of a Koti.” In the skit, a Koti character dies of HIV/AIDS because she could not negotiate safer sex with her promiscuous boyfriend. Her spirit returns to give a pep talk to other Kotis on self-esteem, warn them about her ex-boyfriend and alert them to the dangers of unprotected sex. In the end, the spirit hauls away her ex-boyfriend for an HIV test.

Credit: Courtesy of Counsel Club Archives

This skit was produced years before men who have sex with men (MSM) and trans women were formally included in India’s National AIDS Control Programme in 2007. More than 15 years later, these communities may have been decriminalized, but continue to face stigma and discrimination in health facilities and have some of the highest rates of HIV prevalence in the country.

The skit was performed several times during community- and HIV-awareness generation events in 2001/02 to much applause. Its script survives in the archives, and is a testimonial to the creativity and resilience of queer communities against challenges to their survival. Queer and health activists looking for motivation on continuing the fight against stigma and HIV/AIDS could consider re-enacting the skit and even giving it a contemporary touch.

QAMRA and Varta Trust (which maintains the Counsel Club Archives) are among the first movers in queer archiving in India, and their agenda includes supporting and training other queer individuals and support forums in different parts of India to preserve their own collections. It is early days yet, but as Jayashree says, one of the barriers to cross is the indifference toward the preservation of queer histories. I, too, have come across this indifference, not only among queer activists and groups, but also with the larger archiving initiatives. One exception has been the People’s Archive of Rural India (PARI), India’s most ambitious archiving effort, founded by journalist P. Sainath. PARI addresses the great cop-out of the Indian commercial media in covering the lives of rural Indians, who constitute nearly 70 percent of the country’s population, a group much larger than many countries put together. Since 2018, PARI has been publishing stories on trans communities in different parts of India, though much more remains to be done.

“They may be the only spaces where the ‘little voices’ stand a chance to be heard by the discerning ear.”

For queer activists caught up in the here and now of addressing crisis situations, as I, too, was once, it is understandable that there will be little time and energy for preservation work. Human resources in queer activism are always stretched thin. Fortunately, lack of monetary resources need not be a major barrier. QAMRA has done research within India and abroad to work out archiving methods that are not necessarily resource-intensive, and are kinder to the climate. For instance, there are storage methods that don’t require air conditioning or expensive storage material. These methods can be “good enough” to serve the purpose of preserving memories and stories for whoever cares.

The larger dream is to build an easily accessible network of queer archives across India that provides in-depth information for activists, researchers, lawyers, students and the larger queer community members, perhaps even connecting isolated individuals to support systems.

To be sure, archival endeavours like QAMRA and Varta Trust, unlike the commercial media, are committed to recording all the queer histories and efforts of all the stakeholders involved. They have to be great melting pots of the stories of the Gautam Bhans, Samars and queer spirits of this world, along with those of the “famous and fearless five.” However, as adherents of the principle of neutrality, they may be the only spaces where the “little voices” stand a chance to be heard by the discerning ear.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra