Elliot Page is the most famous trans person in the world.

I don’t think that’s a debatable fact at this point (sorry to Chaz Bono, Laverne Cox and not-so-sorry to Caitlyn Jenner). His coming out as trans in late 2020—and the public conversations he’s engaged in since—have been a monumental shift in the cultural zeitgeist. The man can’t post a simple selfie or speak at an awards show without a pile of overzealous congratulations from one side, and a torrent of transphobic hate from the right.

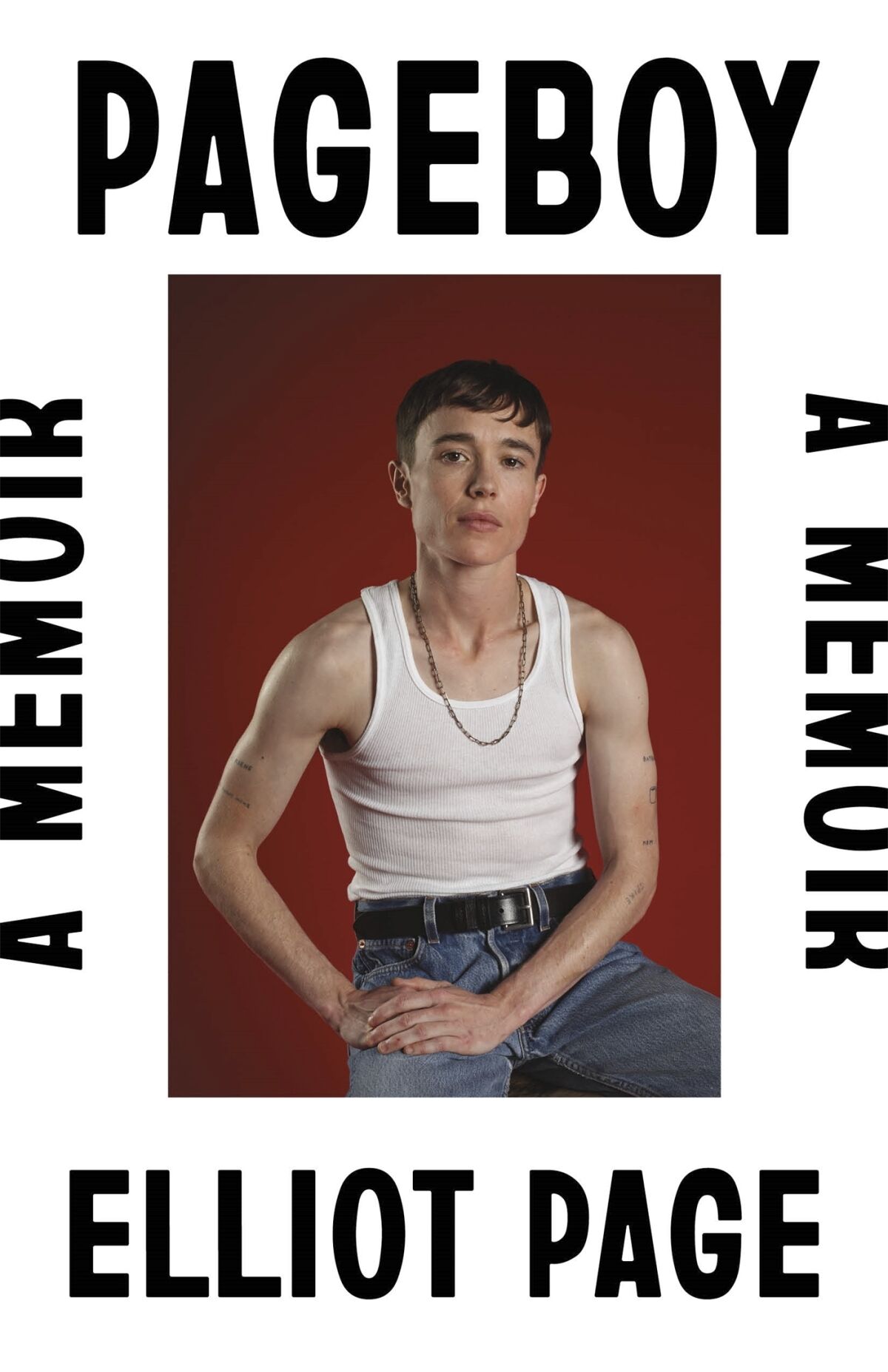

So, understandably, his first memoir, Pageboy, which released June 6, has been hotly anticipated both within the LGBTQ2S+ community and out.

I’ll admit I came into this book with a deeply personal investment. Page’s coming out as trans in late 2020 was a key domino that pushed me over the edge to come out myself six months later. I’ll never forget waking up early for work while staying over at my girlfriend’s apartment, cracking open my laptop and seeing his coming out post on Instagram. “Elliot Page—that’s his name now—is trans,” I remember telling her, and we both sort of sat in shock for a few moments. Not so much surprise, but rather a feeling of how big of a deal it was.

In hindsight, coupled with a string of other semi-public figures who transitioned around the same time, Page’s declaration really was an affirmation of my own gender feelings and almost permission for me too to act upon them. I bought my first chest binders online not long after, and by a year later I myself would be well into my own medical transition. Two and half years later, I’m endlessly grateful that I had that push over the edge.

Not to say that I never would’ve transitioned had it not been for Page, but the immediate connection I felt between his visible relief and things I’d been thinking for years certainly helped the process along. If Elliot Page could live his truth, with all of the scrutiny piled upon him, certainly I could live mine—and certainly in the midst of a global pandemic that had many of us re-evaluating our place in the world.

As a queer Canadian of a certain age (aka, grew up in the 2000s), I’ve always felt an almost parasocial link to Page even before he transitioned. Our trans coming outs aren’t the only ones that happen to be timed—his initial coming out as a lesbian in February 2014 predated my own by less than a year. The Atlantic Canadian queer indie rock band Partner had a song named for his deadname and the experience of being mistaken for him, despite being just “gay and Canadian.” It was the most-played song on my late-night community radio show in university, and when I introduced it I would always joke that it was about me.

I mention all of this because I am certainly not unique in this experience. I myself am not particularly special or deeply linked to Page. There are countless trans kids, trans adults, trans people out there who, like me, had Elliot Page be their catalyst, just as queer folks did the first time he came out. There are countless cis and straight people who’ve learned about transness, or come to better understand it, thanks to Page’s openness and candour over the past few years. That’s the simple reality of having a trans person be that publicly visible—it’s nice to have someone to point to and say “that’s like me.”

But this sort of representation and visibility comes with two sides—because as much as the world perceives, there is still a person being perceived. And that perception is a burden that’s weighed heavily on Page since well before he came out.

And so we come to Pageboy. Not only has Page recently been under a spotlight of trans joy and possibility since coming out, he’s also faced the public spotlight for decades, really, dating back to the success of the film Juno in 2007. There’s more than enough intrigue in his life as a working actor to flesh out a classic celebrity memoir without factoring in queerness or transness. The fact that this memoir manages to weave all of it into a tight 288 pages is a testament to Page’s ability to focus and synthesize the complicated interwoven strings of his life.

Pageboy is not chronological, but rather a series of almost stream-of-consciousness scenes, anecdotes and memories from across Page’s life. One moment we’re reading about his childhood in Nova Scotia, spent shepherded between his parents’ separate houses, the next he’s detailing attending parties at Drew Barrymore’s house or getting harassed with anti-gay slurs on an L.A. street. Over the course of the book, a timeline emerges from Page’s early years acting as a teen, through the massive success of Juno and his subsequent projects both good (Whip It) and horrible (Flatliners) and finally to his transition and declaration to the world.

Page’s writing is accessible, if somewhat meandering. Timelines, scenes and characters blur together, as he shifts through the past and present. He often describes the scene or emotional states where he’s writing from—an apartment kitchen table, a favourite chair at a cabin on the east coast. You can tell this book was not so much an effort, but rather a cathartic release of many, many feelings and experiences that had piled up over decades. While some threads are dropped or become almost too jumbled together—details flying by without getting fully unpacked—I wouldn’t trade Page’s emotional honesty for a more straightforward reading experience.

And it’s certainly honest and open. Page is not afraid to name-drop, and spotting the various famous friends who’ve intersected with his life is a delight throughout the book. I never knew he was so close with Alia Shawket, for example, while a section about an extended romance with Kate Mara is particularly intriguing from a celebrity-gossip angle. Carrie Brownstein makes an appearance, as do Page’s various co-stars over the years ranging from Michael Cera to Hugh Jackman to Kristen Wiig to Leonardo DiCaprio.

The narrative does get incredibly heavy in sections, as Page details some truly horrific abuse he faced in the industry and at home. Struggles with an eating disorder, emotional abuse from family, anxiety, depression and the dark reaches of the closet are all explored in the book, as is Page’s marriage and divorce, and falling out with his father.

But there is light within the darkness too. Most delightful are sections where Page drops tidbits of detail that feel resoundingly queer and unsanitized. Describing sex after coming out as trans he writes, “How deeply freeing to have someone love fucking my dick and my pussy and permitting myself to enjoy it. No longer frozen, that undercurrent, wanting to flee.” Many memorable moments come while smoking joints in backyards. The aforementioned Kate Mara romance (which occurred while Mara was in a long-term relationship with a man) was polyamory among consenting adults. Scenes take place at a Peaches concert or in an apartment with dear friends while recovering from top surgery. Change some names and locations, and these scenes feel like they were drawn from my own life or the lives of my friends.

“Hollywood is built on leveraging queerness. Tucking it away when needed, pulling it out when beneficial, while patting themselves on the back. Hollywood doesn’t lead the way, it responds, it follows, slowly and far behind.”

But the book is also peppered with constant reminders that Page is not me or my friends. His body, face and personality have been under constant scrutiny for essentially his entire life. They will continue to be for likely the rest of his life. And he’s acutely aware of how his queerness, and now transness, have been leveraged in the past and continue to be leveraged. In a section detailing the time in the mid-2010s where he was out personally, but had not yet come out as gay publicly, he writes about the experience of being queer in the industry.

“Hollywood is built on leveraging queerness. Tucking it away when needed, pulling it out when beneficial, while patting themselves on the back. Hollywood doesn’t lead the way, it responds, it follows, slowly and far behind. The depth of that closet, the trove of secrets buried, indifferent to the consequences. I was punished for being queer while I watched others be protected and celebrated, who gleefully abused people in the wide open.”

This book has already and will continue to be covered salaciously by the press, as any celebrity memoir is. The Hollywood anecdotes and insider bits—the Mara romance, a threat from a famous actor, his on-set fling with Juno co-star Olivia Thirlby—will find their way to the pages of People Magazine and TMZ as “big reveals.”

But the biggest reveal of all is the person. And speaking as a trans person deeply influenced by Page, there is something indescribably powerful about seeing your possibility model as a person. Not in a treacly after-school-special way, but simply as a human being who has been through so much, who’s had the same messy feelings and has had to sort them out. I found myself almost getting emotional as he detailed the moment where he decided for sure that he had to transition.

“This was not miracle water that sprang out of nowhere. This was a long-ass journey. However, this moment was indeed that simple, as it should be—deciding to love yourself. There had been multiple forks in the road, and more than once I had taken the wrong path, or not, depends on how you look at it, I guess. It is painful, the unravelling, but it leads you to you.”

In many ways, this book is part of that unravelling. And I’m glad it exists. In press coverage and promotion, Page has almost seemed visibly relieved that it’s done—the things have been said, the journey has been unravelled and now he’s free to move forward in life. He deserves that.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra