Local celebrities have a special place in the pantheon of stars, giving even the smallest city integrity and charisma.

I moved to Toronto from Montreal seven years ago and, almost immediately, began hearing things about artist, filmmaker and musician GB Jones. She’s an interesting local personage because Jones is, in fact, known more abroad, and in specialized pockets, than she is in her own city, where locals enjoy the impact of the art, music and politics she’s been putting out for more than 20 years.

“Ground zero,” is how artist and DJ Will Munro describes Jones and her work. “She influenced me to create queer space where it doesn’t really exist already.”

“The scene that GB and her friends had created through [the zine] JD’s was so inspiring for a young fish like me because it portrayed a self-created mythology full of perversion,” says artist Luis Jacob. “They basically sent the message that if it’s bad, it’s good. They were against the gays who believe that gay is the same as normal.”

“GB was always ahead of her time,” adds filmmaker Bruce LaBruce. “She taught me the value of underexposure. She always said it was more glamorous not to show up somewhere and leave everyone wondering where you were than to show up and spoil the mystery.”

In the words of journalist Kristine McKenna describing Pauline Kael, Jones carries herself, “with a dignity that discourages one from asking personal questions.” People have speculated for years about Jones’ ambiguous sexual persona. In an age of increasingly laboured and narcissistic self-identification – and as someone drawn to paradoxical, self-styled women – I find this very alluring.

Trendy clubs and magazines that capitalize on queer cachet have Jones to look to for fostering the talent that grew up on her impulse. Always the radical, she’s long addressed this in her work.

“There’s a phenomena in the mainstream media where they can make a lot of money out of marginalized people, different sub-cultures,” she says. “They just kind of suck them up, use them for what they’re worth and toss them out and say that trend’s finished.” Referring to a 1993 drawing called Shopping, which takes on queer culture kleptomaniac Madonna and mainstream magazines, she says, “That had to do with the impetus of when we created queercore, because that was a culture produced by queer people for queer people. The comparison was with the mass media, that uses queer people to sell products, that will not engage in any political support for the most part for them.”

For those too young, conventional or new to town, here’s a crash course in GB Jones: With friends, she started the homocore scene in Toronto. This scene spawned events like Vazaleen and bands like The Hidden Cameras. She was in a seminal queercore band called Fifth Column, to which current bands like Kids On TV and Lesbians On Ecstasy pay tribute. She is an internationally shown artist who lives quietly in the city she made widely understood as a hub of queer punk culture in the mid 1980s. This is when LaBruce lived with her in a condemned building. “That’s when we started publishing JD’s together, the homocore fanzine that launched the movement,” he says. “We pretended that there was already a fully fledged homo punk movement in full swing going on in Toronto.”

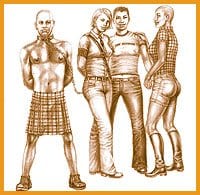

The Power And The Glory, the upcoming survey of Jones’s work at Paul Petro Gallery, brings many of her interests as an artist and agitator to the present. She says the drawings are all in pencil “because it doesn’t cost anything and it’s always available.” They cover the 20-year span of her career, and several, in the style of ’50s physique magazines, originally accompanied the text and pandemonium of JD’s.

“I was looking to clarify certain areas that I had been working on,” says Jones. “I was interested in certain issues that I don’t think many people may have picked up on in the work, ideas about authority figures, power, obviously, and the abuse of power, and gender roles as they pertain to both sexes. I think there’s been a tendency to take a very reductivist view of the work as simply erotic and kind of dismiss that there could be any other concerns involved.”

Certainly, Jones’s drawings have a deliberate sexual quality to them (unlike so many other feminists of the early ’80s, she was and remains pro-sex), and her most common comparison has been to Tom Of Finland, after whom she modelled her style. In many ways, the two couldn’t be more disparate. “I thought it would be interesting to compare the effects that [style] has if you were familiar with Tom Of Finland and you’d be able to compare the effect of women in those positions of authority versus the men.

“But then I always try to change the narrative, I don’t go in the same direction. He is totally: ‘Cops are great, they’re really hot, we all want to have sex with them.’ In my work it’s more like: ‘Cops are fascist pigs and we’re going to tie them up and beat them and then drive away on our motorcycles.’ His work stays purely in the fantasy realm, and I try to make my work more a bit more realistic.” She pauses and laughs, “Although you can’t really tie up cops and beat them without risking your life. So I guess that’s where the fantasy comes in.”

Jones gives her marginalized female characters a place to reclaim their power, and in her world, they always get away. When describing a 1990 piece called The Shoplifter, where a young punk girl is caught stealing in front of a punk clerk by an older wealthy patron, she says, “I’m placing the viewer in the same position as the shop clerk is in. What do I do now? Do I let myself prevail and let them go, or do I have to act like an authority figure and uphold all the laws and supposedly morals of a commercial society, where people are of no value and commercial items are of value? The situation the shop clerk is in dictates that she give precedence to the object rather than the feelings of the person herself.”

Artist and cultural critic Allyson Mitchell, who is writing the show’s accompanying essay, says, “GB Jones showed me a practical example of how sex and art come out of politics. Her work encourages me to maintain a cheeky, sexy, radical queer edge in my own art practice and it serves as a touchstone whenever I feel crazy for doing so. She ain’t no L-Word. She’s the real deal.”

Indeed, it is Jones’s personal politics that are the most meaningful aspect of her work. She treats her own culture, the one affecting real change and providing real internal support, with great affection and significance, while treating the prevailing culture, which tries at every turn to abscond with our culture and sell it back to us, with suitable disdain.

* GB Jones’s video The Trouble-makers screens at the gallery as part of Inside Out beginning Fri, May 20, with an opening reception from 7pm to 10pm.

GB JONES: THE POWER AND THE GLORY.

Opening. 7pm-10pm. Fri, May 6.

Continuing till Jun 3.

Paul Petro Gallery.

980 Queen St W.

(416) 979-7874.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra