Opera Atelier artistic director Marshall Pynkoski is fired up about remounting CW Gluck’s revolutionary opera Iphigénie en Tauride. “It’s a wonderful, wonderful work,” Pynkoski says.

“Gluck was redefining what opera should be. He wanted to cut through the excess of opera of the 18th century and get down to opera being something that tells a story clearly and concisely. So if there are dancers on stage, he wants the dancers not to be an interlude, he wants them to be integrally involved in the action. He doesn’t want to have superfluous ornaments. He doesn’t want to have ridiculous arias that are just there to show off.

“So we end up with a very complex and extremely dramatic opera that is only two hours long,” says Pynkoski.

Despite his admiration for the work Pynkoski always felt something was missing. “There’s not the love interest that you normally associate with 18th-century opera,” he says. “You immediately think Iphigénie — she’s the soprano or mezzo. So who’s the love interest with Iphigénie? If someone answers her brother, her deep concern she has for her brother, that doesn’t seem terribly interesting or exciting.”

After years obsessing over the opera Pynkoski realized the missing element was staring him in the face — a gay love story.

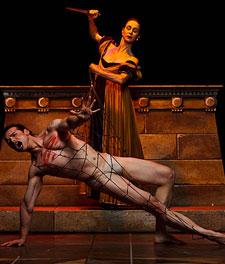

The Greek princess Iphigénie, daughter of Agamemnon, is held as a captive priestess on the island of Tauride during the Trojan War. In Gluck’s 1779 opera Oreste, Iphigénie’s brother, is forced by a storm to Tauride. Driven inland by furies (he killed his mother after all), he and his companion Pylade are imprisoned and face sacrifice. Iphigénie has a plan to free one of them to fetch help; the two men fight over who should live, each offering himself to save the other.

Pynkoski says he’d “draw a complete blank” every time he came to the prison scene.

“One day I was listening to that scene again and it was truly like an epiphany. I just remember thinking, ‘This is ridiculous. They don’t sound like friends, they sound like lovers.’ And the moment I thought it, it felt like something had been dropped on my head.

“You know, I couldn’t write fast enough, I couldn’t get the staging down fast enough. It just did itself. It was so real. It was so natural.

“I got in touch with Brad Walton, a dear friend who is a classicist at U of T. And I just said, ‘Brad, you have to tell me, am I way off in looking at the relationship between Oreste and Pylade like this?’

“I got this wonderful email back from Brad. The first thing he said was, ‘Dear Marshall. You’re in luck. You’re talking about the most famous gay couple in classical history.’” (For Walton’s essay on Oreste and Pylade go to Operaatelier.com.)

“[Their love] is simply an integral part of the story that anyone in the 18th century would have been familiar with,” says Pynkoski. “With their style of classical education they knew what the relationship was between Oreste and Pylade…. They grew up with these stories.”

Pynkoski calls his Oreste, celebrated Croatian tenor Kresimir Spicer (last year’s Idomeneo), one of the greatest singing actors in the world. “I still can’t believe I’m working with him. I look at him at rehearsal and think it’s like a dream.”

Because of Spicer’s huge physical, vocal and emotional presence, Pynkoski had a hard time casting Oreste’s companion, Pylade. “Pylade has to protect him. I mean that’s like protecting a grizzly bear he’s so big.”

“We heard many, many tenors. Finally, as it turns out, this beautiful young man right here in Canada we had never heard of who had just graduated from the Atelier Lyrique in Montreal, Tom Macleay, who in terms of his height, his size, the size of his voice — a beautiful, beautiful match for Kres.

“Peggy Kriha Dye, who of course is my favourite, favourite soprano, is singing the role of Iphigénie.” All three are debuting their roles. Andrew Parrott conducts the Tafelmusik Orchestra and Chamber Choir.

—–

When Opera Atelier first mounted Iphigénie en Tauride in 2003 reviews were split: Some heralded the production as a pinnacle of OA’s seamless, sensual storytelling through music and dance; others got hung up on the passionate tenderness displayed between Oreste and Pylade.

“It was staggering,” says Pynkoski. “I couldn’t believe what I was reading. I couldn’t believe it was Toronto. We had one reviewer actually arguing, ‘We know Gluck was straight. So this can’t be what he meant.’ Literally, that was the argument. He was a straight man, so why would he write an opera in which the two male protagonists are romantically attached to each other. I mean, where do you go from there? The ignorance is unanswerable.

“I’m sorry, it’s just classic homophobia.

“I was more shaken by those reviews than anything we’ve ever had before.”

Sniffy critics notwithstanding OA audiences, gay and straight, love the company’s sensuality — and its penchant for cleavage hoisted at full mast and painted-on tights. “I’m a dancer. I come from ballet. That’s my background. I adore the physicality of it. I love the fact that the bodies are meant to be eloquent. Bodies can talk.

“It was Balanchine who said, ‘The more dancer you have the more dance you see.’ I don’t want to encumber our singers and dancers with massive amounts of superfluous clothing…. I don’t want to dress the singers and dancers differently. I want them to look like they come from the same world, so it doesn’t suddenly look like some beautiful people come on and entertain us and then the singers lumber on to the stage.

“It creates a complete world… and it’s simply sensual. Period. I don’t like to think of sensuality as being gender specific. Beautiful bodies are beautiful bodies. Skin is skin. Two people throwing their arms around each other in contact of skin against skin — that’s drama, that’s thrilling.”

OA’s style of historically informed baroque productions has evolved in recent years. It’s less formulaic now, incorporating a broader range of movement and gesture — anything that works for a particular story.

“There’s a wonderful quote of Cocteau’s — he was talking about something filmic, but I think it applies to everyone. He was saying, ‘Every scene in a film has a bull’s eye. There’s a target, there’s a bull’s eye. Style is what we use to take aim.’ That’s what style is — this is the greatest stylist in the world talking. But then he went on and said, ‘If you confuse style with the bull’s eye, if you think that’s what it is, you are going to hit a brick wall eventually. It’s going to be stillborn. People may be fascinated at first, they may be shocked, but eventually you’ve got nothing.’

“And I thought what a brilliant observation. Every young person in theatre begins obsessed with style. It’s a good healthy place to begin with. And we did as well.”

Pynkoski remembers a rehearsal a few years back where a singer created an exciting action for a scene — pulling his hair with both hands. But Pynkoski worried about the huge baroque wig. “I suddenly thought, ‘What am I saying? Is this scene about a wig?’ How stupid. The wig goes…. So when we got rid of his wig we got rid of all the men’s wigs. The moment we did that all the women looked like they had Shetland sheepdogs sitting on their heads. So the girls’ wigs went. But when those went, the costumes had to come down. Suddenly it was like a house of cards.

“You know we’ve never looked back.”

That renewed commitment to the emotional core of any story — substance over style — circles back to Iphigénie en Tauride.

“For me there is not a more beautiful opera than this,” says Pynkoski. “We always felt it was a turning point for us: a turning point dramatically, in terms of integrating the dancing and singing; as well gesturally, that the singers became bigger and even more emotionally involved in the gestural style of acting that we use. We turned a corner with Iphigénie and we’re just continuing to go that way.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra