“And they lived happily ever after.” It’s the guiding light at the end of the tunnel of lurve, the perfect ending to a fairy-tale romance. But the magic spell that allows us to find a prince or princess has always seemed to be reserved for beautiful, straight, white, able-bodied people whose mental health is strangely impervious to abuse, neglect and multiple other forms of trauma. Fairy tales, we are made to believe, are not for queers. Cishet culture’s magic trick of making itself seem natural, inevitable and universal depends in part on the ubiquity and repetition of fairy tales throughout our lives. We are told these stories of compulsory heterosexuality from cradle to grave—and even though everyone knows they are just fantasies, their enchantments are so seductive that it is difficult to resist their charms and not wish we could all live the fairy tale. And yet. The fairy tale realm is the perfect place for the shifting, resisting, transformative and hard-to-pin-down cultures of LGBTQ folks. Ignore the happily-ever-after endings that imply a kind of blissful stasis that goes on and on forever. The wonder-filled, strange and surprising worlds of fairy tales have the potential for a kind of queer enchantment. Don’t let all those ever-after weddings fool you: Fairy tales are the perfect environment for LGBTQ folks and queer desires.

“The wonder-filled, strange and surprising worlds of fairy tales have the potential for a kind of queer enchantment.”

Queers have appeared in literary fairy tales since at least 1695 with The Story of the Marquise-Marquis de Banneville, a tale attributed to François-Timoléon de Choisy, Marie-Jeanne L’Héritier and Charles Perrault. But rather than creating a list from the last 325 years, I chose to narrow it down a bit. These stories were all published in the last decade of the 20th century or the first two decades of the 21st century, and they all include overtly queer desires. You won’t need a queer decoder ring to “get” it. I am not looking for “sisters” as in Christina Rossetti’s Goblin Market, or questioning the sleeping arrangements of the Seven Dwarfs off the page. Each of the following texts features lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans and queer people as main characters. (Two-Spirit and other queer and trans Indigenous stories are not included here because fairy tales are historically a Euro-American genre, and I don’t want to imply that the wonder tales of Indigenous people are the same as traditional fairy tales.) I’ve limited the discussion to works that are short in length, like the “classic” well-known tales of Charles Perrault or the Brothers Grimm. We are not talking about fairy-tale novels or full-length feature films (so long, Disney), or even collections that weave fairy tale and folktale motifs throughout. (Sorry, Carmen Maria Machado. Love you, but 2017’s Her Body and Other Parties and 2019’s In the Dream House complicate matters by intertwining fairy tales and other genres.) Finally, these are stories aimed at primarily adult audiences who can enjoy them on a “grown-up” level, rather than as an exercise in childhood nostalgia or as a COVID-19 child’s reading list. The few collections listed here suggest a field that is wide and varied. Contemporary fairy-tale fiction, film and art offer new spins on old tales that are steeped in both kinds of wonder: Amazement at the magic of seemingly impossible things, and the intellectual curiosity of “what if?”

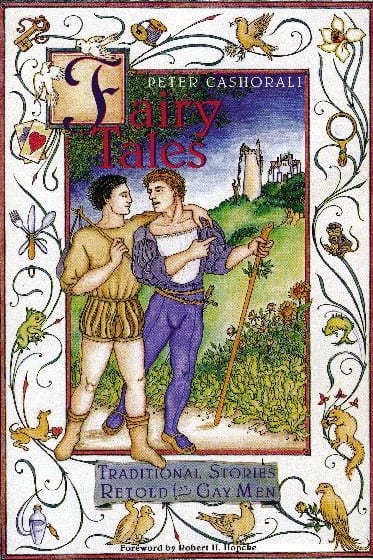

My first example of contemporary queer fairy tales comes from Peter Cashorali’s Fairy Tales: Traditional Stories Retold for Gay Men from 1995. These sexy revisions, told in the compact, artless style of the Grimms or Andrew Lang’s “Coloured” Fairy Books (published from 1889 to 1913) take classic tales such as “Beauty and the Beast” and “Handsel and Gretel,” meld in elements of less well-known tales, and plug gay men and boys into the them. But more than just mixing-and-matching gender reversals, Cashorali rejigs the desires and themes to address contemporary issues and the many different identities of gay men. These short, simple revisions can be gobbled down quickly, like the macadamia-nut brittle candy door of the enchanting drag mother who takes in and trains Hansel. Or they can be savoured more slowly, like the scent of the orchids and lessons the dominant Beast has for his submissive Beauty.

Emma Donoghue’s 1997 collection Kissing the Witch: Old Tales in New Skins, also retells well-known fairy tales (and includes one new tale). Rather than the distant, omniscient narrator of traditional tales that Cashorali employs, Donoghue allows the women in her tales to tell their own stories. In doing so, she gives these normally voiceless characters the ability to articulate their own desires. While the language and rhythms of Kissing the Witch are beautiful, its magic is in its structure, which interweaves the lives of the protagonists into each other’s tales. For instance, at the end of “The Tale of the Shoe,” the Cinderella figure asks her new lover/fairy godmother who she was “before you walked into my kitchen?” The reply comes in the form of the next story, “The Tale of the Bird.” And so on it goes, each tale calling the next into being until the final story, “The Tale of the Witch.” This story draws you even further into the intimacy of the relationship between teller and listener, when the witch finishes telling her story and leaves it “in your mouth.”

Shifting our attention from mouths to eyes, Maya Kern’s web comics entwine visual images and original narratives rather than retellings. For example, Fairy Fail, published in 2011, is a contemporary love story framed both visually and thematically with fairy tale images. A girl who cannot tell a lie falls for a woman who never tells the truth. Although they live in a mundane world and there are no magical transformations or interventions, falling in love becomes a kind of enchantment itself. The lies begin to wrap around the couple like the barbed rose vines surrounding Sleeping Beauty’s castle, until one of the lovers wakes up. The question then becomes: Is love a charm that can dispel the pricks of so many lies, or were the lies a spell that created an illusion of love?

Sleeping Beauty appears as a touchstone in another, very different kind of queer fairy tale. Diriye Osman’s “Fairytales for Lost Children,” from his 2013 book of the same name, is more realist and historically situated than any of our tales so far. Its magic lies in how Osman captures the enchantment of fairy tales in childhood, especially for a child who could use an escape from the horrible real world around him. For Xirsi, a Somali boy who fled to Kenya to escape civil war in Mogadishu, Disney’s Sleeping Beauty provides a beautiful fantasy in dark times. But Xirsi learns that “the road to happily ever after…was paved with political barbed wire,” and that his kiss will not work to wake Ivar, his first crush. But Xirsi is not the only one who knows the power of fairy tales: His teacher tells the children revised fairy tales such as “Kohl Black and the Seven Street Boys,” and the consequences of her revisions show the political implications these so-called frivolous stories have in our real world.

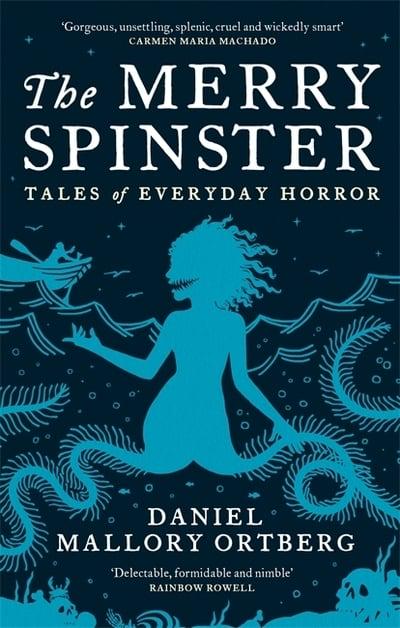

Daniel M. Lavery’s 2018 The Merry Spinster: Tales of Everyday Horror offers off-kilter wonder tales that create gender-queer worlds of strangely familiar and unusual juxtapositions. These tales challenge assumptions about storytelling and comprehensibility, boldly and without apology or explanation. In “The Frog’s Princess,” for example, “It was the man’s youngest daughter who was the unluckiest of all. He was so beautiful that the sun herself noticed and had in fact fallen quite in love with him.” It is not the daughter’s gender that is the problem, it is his beauty and the strictures it places upon him. The Merry Spinster’s dark caprice, social critique and wide-open endings create engaging and thoughtful absurdities for 21st-century readers. These stories intertwine folk and literary fairy-tale tropes with Christian tales, canonical Western literature and a great deal of whimsy. The tales walk a dark line; they lay bare emotional abuse of intimate partners and of society as a whole, but they also offer up the wonder of the fairy-tale realm—all the while refusing ever afters, let alone unquestionably happy endings. As Osman says in his essay “The Queering of Sleeping Beauty”: “I realized only in hindsight that my queering of the Sleeping Beauty narrative was an unconsciously political act, that in fact every appropriation of any cultural text is an inherently political act whether we acknowledge it or not.” Similarly, while it may not seem like it at first, simply reading these fairy tales is a political act—and an enchanting one. Take them as you will: As carefree escape in an unprecedented time of fear and uncertainty, or as a politically-informed “fuck you” to hegemonic heteronormativity’s presumed stranglehold on magic and wonder. Happily, fairy tales are not the property of straight culture and there is plenty of queer enchantment to go around.

Inviting Interruptions: Wonder Tales in the 21st Century, edited by Jennifer Orme and Cristina Bacchilega, will be published by Wayne State University Press in the spring of 2021.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra