Some time in the last month, I started using the phrase “the first Trump administration.” As in: I’ve started to assume there will be a second one. Trump looks all but certain to be the Republican nominee. Polls show him pulling ahead of Joe Biden going into 2024. If Trump takes office, precedent shows that he will probably refuse to leave it: “There is little doubt that a second-term Trump would be extraordinarily dangerous to the Republic,” writes political historian Julian Zelizer at CNN. At the Washington Post, conservative critic Robert Kagan warns that a Trump dictatorship is “increasingly inevitable.”

A strong free press is supposed to safeguard against the rise of dictators. It is supposed to hold the powerful to account and educate the people about what their leaders are doing. Since 2020, that free press has been badly damaged, if not dismantled—and this failure is especially glaring when it comes to trans people, who are routinely underserved by mainstream media coverage while also being the obsessive focus of the right wing’s culture war. The media infrastructure that allowed queer and trans people to communicate with each other, push back on irresponsible journalism, produce coverage of our own issues and learn about the political landscape is being demolished just as we need it most.

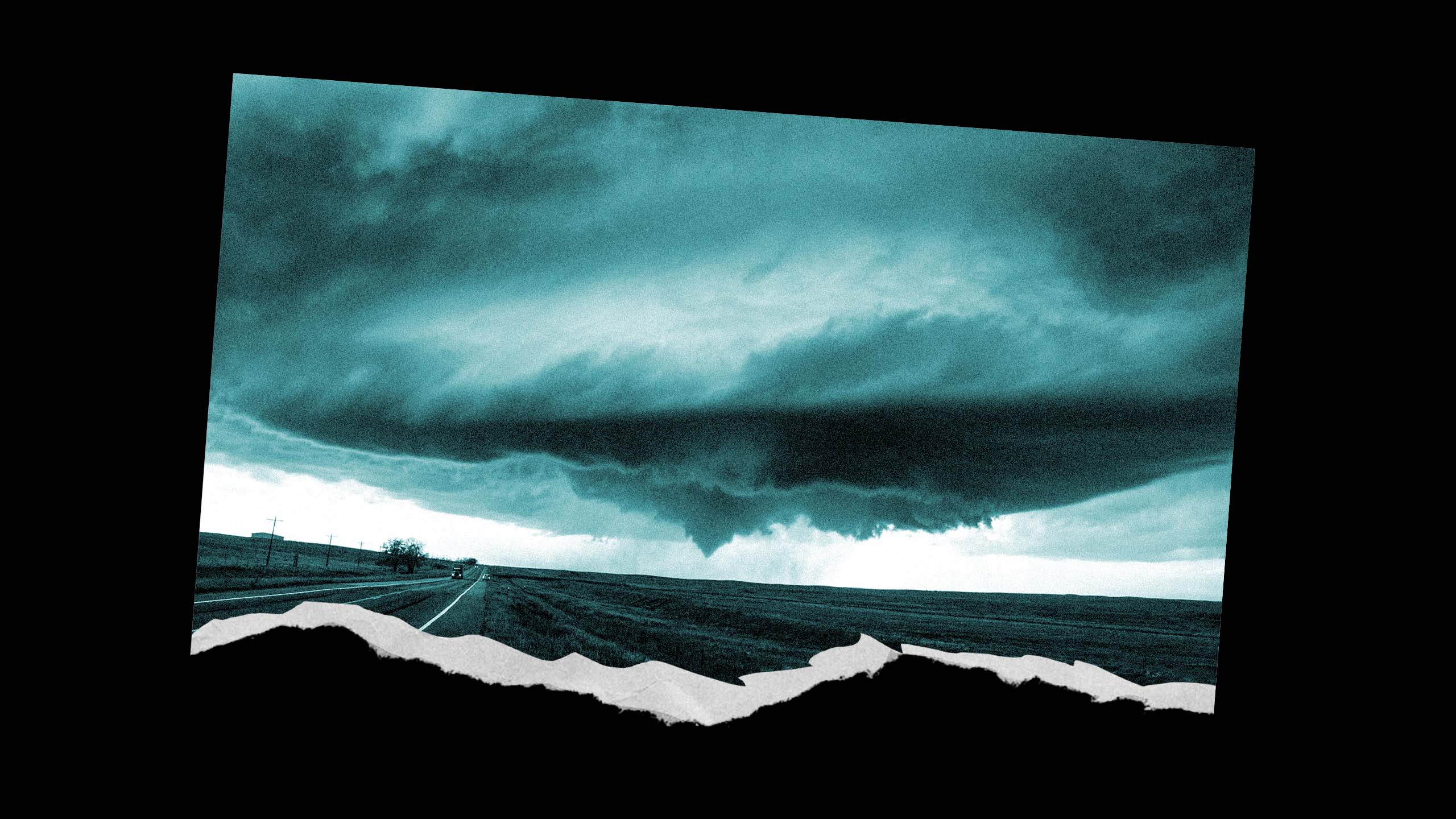

Most trans and queer people have an understanding that the U.S. media is bad on trans issues right now, but we tend to see only individual failures, without necessarily knowing how all of the different problems are connected. The truth is that the situation has come about thanks mostly to a small handful of interconnected players with right-wing sympathies and more money than sense. This is the year we fly blind into the hurricane; but before chaos takes over, it’s worth discussing how we got here.

News media in the U.S. is the hostage of capitalism. Every publication has two obligations—to inform the public, and to make enough money to stay in business—which are often starkly opposed. That tension has increased considerably in the past 20 or 30 years. The internet and social media disrupted existing business models for newspapers and magazines, and ever since, publications have been struggling to come up with new ones that work.

Since 2020, we seem to have crossed some invisible line that separated “disruption” from full chaos. This is a failure across multiple fronts, but the breakdown does tend to be more glaringly obvious when you focus on legacy media coverage of trans issues.

The New York Times, for instance, has conducted what Tom Scocca calls a “plain old-fashioned newspaper crusade” against gender-affirming care, running reported articles that are little more than laundered talking points from hate groups and seemingly allowing opinion columnist Pamela Paul to make transphobia her full-time job. The anti-trans viewpoints expressed by the Times and other mainstream outlets would have seemed extreme five or even 10 years ago, during the “Transgender Tipping Point.” I can’t think of a single person other than Pamela Paul who takes Jesse Singal’s trans coverage seriously—but, in her former capacity as books editor, she gave Singal a Times byline, through which he promoted a book that frames trans people as part of a sinister Jewish conspiracy.

It’s not just that coverage of trans issues has stalled. We are actively going backward. But the Times is just one part of a larger media ecosystem, and the mainstreaming of transphobic disinformation and conspiracy theories didn’t begin at the NYT. The canary in the coal mine was most likely Substack, the newsletter platform that poached some big names from legacy media—Glenn Greenwald, Andrew Sullivan, Matt Yglesias—and set them loose to spew increasingly unhinged anti-trans viewpoints.

Bigots show up on every internet platform, but not only has Substack tolerated hate speech, it has increasingly defined its brand around supporting it. Recently, CEO Chris Best refused to say that he would ban or moderate users who called for all brown people to be ejected from the country, and white supremacist blogger Richard Hanania was promoted by co-founder Hamish McKenzie on his podcast. After the Atlantic reported that the site now hosts and profits from many Nazi and white nationalist newsletters, over 200 Substack users signed an open letter asking Substack management to explain its stance; on Dec. 21, McKenzie responded, saying that “we [at Substack] don’t like Nazis either” ([citation needed] on that one, Hamish), but that “we are committed to upholding and protecting freedom of expression, even when it hurts,” and thus, Nazis were explicitly welcome to generate incomes and audiences through Substack.

Substack freed a certain type of shitty media man from the editorial standards, oversight and pushback that would have reined him in at a legacy publication. But the real problem was the money. Substack bragged that it could make its writers rich through subscription revenues, and in 2021, readers learned that the company had begun secretly paying out huge advances—like the staggering $250,000 given to Yglesias—to certain writers, thanks to substantial funding from venture capital firm Andreessen Horowitz. (Remember that name.) Those advances were clearly intended to help Substack compete with—and, eventually, replace—legacy media outlets by poaching star writers. The $200,000 offered to anti-abortion columnist Elizabeth Bruenig was twice the size of her yearly salary at the New York Times.

To the extent that anti-trans culture war has become trendy at the NYT and other legacy publications, it is probably because they are chasing the popularity and (largely illusory) financial success of Substack and other, even less reputable outlets. Again: publications struggle to make money, and even the stodgiest will adapt to emulate successful rivals.

Of course, coverage of marginalized people has never been the mainstream media’s strong suit. The NYT made disastrous decisions when covering Black Lives Matter, and its coverage of the AIDS crisis wasn’t great. But, in the past 15 years or so, social media has allowed marginalized communities to push back on dangerous or misleading narratives, as well as to organize and create counter-narratives of our own. This was particularly useful on platforms like Twitter, which broke both the news and the queer and trans response to that news in real-time.

This brings us to the final part of our puzzle: billionaire and serial edgelord Elon Musk. Since buying Twitter (now named X) in 2022—in an acquisition partially financed by Andreessen Horowitz—Musk, too, has gone out of his way to cultivate and uplift extreme right-wing perspectives. He has restored the banned account of Sandy Hook truther Alex Jones. He recently hosted a Space discussion with Jones, Republican presidential candidate Vivek Ramaswamy and sex trafficker Andrew Tate. His distaste for trans people—including his estranged trans daughter, whose transition reportedly sparked his obsessive interest in quashing “woke” culture—is infamous. X has become unusable for many trans people due to widespread harassment. Given that one of Musk’s first priorities as CEO was to remove the site’s rules against misgendering, it’s hard not to see that as the intended outcome.

Altogether, three mainstays of public discourse—legacy media, social media and the informal network of pundits and opinionators we used to call the “blogosphere”—have taken a hard right turn in the past four years, and have become either hostile or outright unusable for many queer and (especially) trans people. But why? How does this happen? How intentional can any of it be? Once again: this is a story about money. For answers, you have to follow that money back to its source.

In October 2023, Andreeessen Horowitz co-founder Marc Andreessen published what he called a “Techno-Optimist Manifesto.” The document, widely decried as troubling, is certainly a manifesto, and could definitely be described with a word ending in “-ist,” though “optimist” isn’t the first one that springs to mind. Bluntly—and I’m sorry, but there is no more professional way for me to put this —the Hitler vibes here are off the charts.

There’s talk of Übermenschen. (One section is headlined “Becoming Technological Supermen.”) There are extensive quotations from Nietzsche. There’s a strange fascination with Ancient Greek and Roman aesthetics of the RETVRN-guy variety. There’s a dollop of nationalism (“we believe America and her allies should be strong and not weak … a technologically strong America is a force for good in a dangerous world”) and a list of macho qualities the technomenschen must embody: “We believe in ambition, aggression, persistence, relentlessness—strength. We believe in merit and achievement. We believe in bravery, in courage. We believe in pride, confidence and self-respect—when earned.”

Indeed, you might say that this world view “wants man to be active and to engage in action with all his energies; it wants him to be manfully aware of the difficulties besetting him and ready to face them. It conceives of life as a struggle in which it behooves a man to win for himself a really worthy place, first of all by fitting himself (physically, morally, intellectually) to become the implement required for winning it.” That last quote is not Marc Andreessen; it’s Benito Mussolini’s 1932 “Doctrine of Fascism.” But hey, if the jackboot fits.

Though Andreessen claims his ideas are bipartisan, he characterizes his enemies as explicitly leftist: “Our present society has been subjected to a mass demoralization campaign for six decades—against technology and against life,” Andreessen writes; ideas such as “social responsibility,” “trust and safety” and “tech ethics” are a front for that campaign, “derived from Communism.” To make sure you get the point, he throws in a few more red-baiting synonyms: “Our enemy is statism, authoritarianism, collectivism, central planning, socialism.”

This is where Substack got its early money, and this is also where Elon Musk got at least some of the money to buy Twitter. When you take Andreessen’s world view into account—as well as the far less hidden alt-right sympathies of Elon Musk—the decay of the media institutions in question starts to seem a lot more like a planned demolition. American media’s right-wing drift is not the result of a slowly evolving zeitgeist, it’s the work of a handful of guys who all more or less know each other: Not only did Andreessen finance both Substack and Musk’s acquisition of Twitter, one Andreessen Horowitz blog post says that Hamish McKenzie was both the Substack team member who initiated contact with Andreessen Horowitz and the former lead writer at Elon Musk’s Tesla. It’s hard to describe the situation without using the term “circle jerk”; so hard, in fact, that I will not attempt to describe it any other way.

It’s important not to resort to conspiracy theory here. This is not a shadowy plot to take over the world, it’s just capitalism doing what it does: as power and money are concentrated in fewer and fewer hands, it takes only a few bad actors to make life hell for everybody.

It’s enough to say that Substack and X have destabilized the media landscape, allowed formerly marginal right-wing views to obtain large and profitable platforms, and weakened traditional journalism through their influence. Media is a business, but even for-profit newspapers traditionally operated with the understanding that you could not just print a story because it would sell copies—it also had to be true. That is no longer the case. The impact of these platforms has not just been to spread bigotry, but to flood the field with junk, to make social media gossip and un-fact-checked blog posts the main vector for information—to make it harder to know what is real. In an emergency, you need to know where the exits are, but at least half of the signs you’ll read in 2024 are lying to you.

It is always in the best interests of the powerful not to have a robust press that can hold them accountable. This is true whether you’re an American Mussolini or merely an Ayn Rand–loving tech bro convinced that “communists” are out to stop you from colonizing Mars. It is ultimately not surprising that the goals of these two parties would be mutually reinforcing. Even the most ardent transphobe won’t be safe if these guys succeed in reshaping the media landscape: Andreessen’s latest fascination is AI. The newsletter era may have deprofessionalized journalism and turned it into one more low-paying gig-economy job, but even that is less effective than getting rid of human journalists altogether.

So, back to the first question: why trans people? Why should it be that a publication’s expressed hostility to trans people is such a reliable predictor of right-wing drift, or the deterioration of its standards overall? The answer, at least as far as I can figure out, is that it’s not just trans people. We’re easy to target, because we’re a small and historically despised minority with very little institutional power. But the same disregard for truth or human dignity that leads to institutional transphobia eventually ends up harming everyone. The year 2024 is when trans people fly blind into a hurricane, but everyone else is headed into the storm along with us. Hang on tight, buckle your seatbelt, brace for impact; here comes the future, and it’s coming fast.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra