There’s a moment early in the first episode of the newest season of Netflix’s Feel Good where the fictionalized version of comedian Mae Martin has checked themself into rehab.

“I don’t actually identify as a woman these days, just so you know,” they say in response to why they missed “women’s yoga.”

“What do you identify as then?” a rehab worker asks.

“I dunno, kind of like an Adam Driver or a Ryan Gosling? I’m still, like, working it out.”

It’s the first of several throwaway lines throughout the season where the fictional Mae works to nail down what their gender is (cinematic hitman John Wick is also brought up as a possibility). The approach is a refreshing moment of ambiguity and levity that reflects the real-life experiences of many queer folks sorting through their identities and how they want the world to see them.

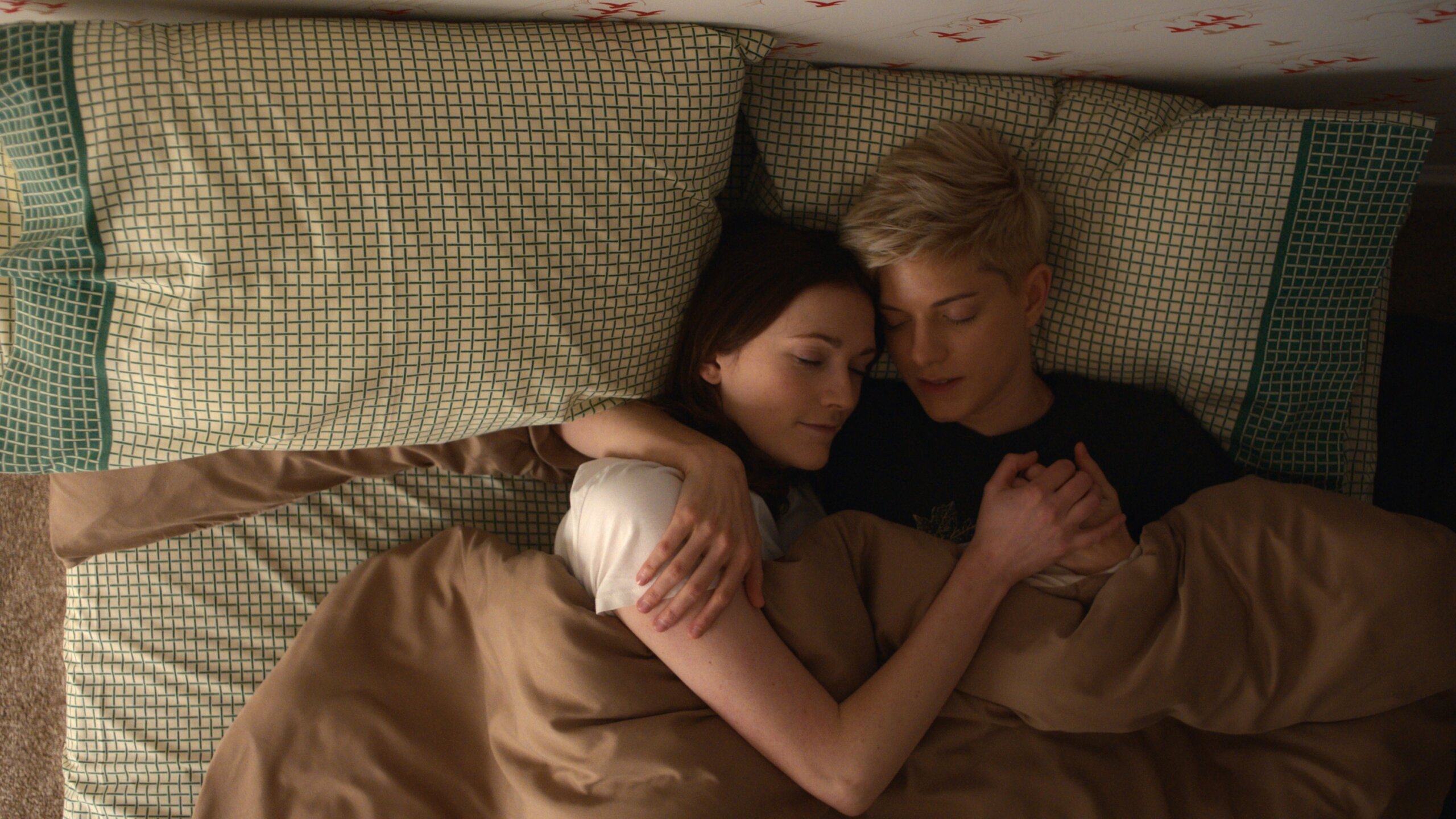

Despite these nuanced explorations, Feel Good isn’t even really a story about gender. Both six-episode seasons of the Netflix show present a complicated look at relationships, trauma, addiction and the world of standup comedy. The story is inspired by Martin’s own experiences, and follows a fictionalized version of Martin as they start a relationship with a repressed schoolteacher named George (Charlotte Ritchie) and navigate addiction.

Credit: Netflix / Courtesy Everett Collection

While the series’ first season largely focused on the relationship between Mae and George, its second season takes a deep dive into reckoning with trauma, recovery and abuse in standup comedy (something it shares with HBO Max’s Hacks). And while those may sound like hefty topics, they’re punctuated by Martin’s characteristic humour.

The 34-year-old real-life Martin has been on the standup stage since they were 13. After writing on Canadian shows like Baroness Von Sketch, they made the move to the U.K. in 2011. The first season of Feel Good dropped on the U.K.’s Channel 4 and Netflix back in the spring of 2020, and its successor premiered earlier this month. Martin also came out publicly as non-binary earlier this year.

I sat down with Martin to talk about the series’ second and likely final season, fluidity and getting back in the standup saddle. And of course, like any good pair of masc blonde queer folks, we turned up wearing the exact same outfit.

I burned through the second season of Feel Good in one night. There’s so much going on—from frank discussions of gender to addiction, to grappling with trauma. I’m curious what you hope people’s biggest takeaway from the second season is?

That’s a good question. I try to think about the shows that have made an impact on me, or the books or things like that, and the main thing is that I hope it stays with people and that it makes them think about things and feel emotions. One thing that I’ve been really touched by and pleased about is people saying that about the show.

Some of the themes that come up in the series are very topical at the moment, but the way that they’re discussed in the public discourse around things like trauma or gender identity is so fraught and it’s so polarizing and kind of alienating and also just very intense. I hope that people are reminded through watching the show that these are very human and relatable experiences that are very nuanced and much more complicated than a tweet.

I know a lot of people who’ve personally really connected to how your character talks about gender in this season. I really enjoyed how they used people like John Wick to describe themself. Can you tell me a little bit more about that?

I don’t know what it’s like in Canada at the moment, but there’s just a kind of hysteria around gender in the U.K. right now. There’s been a huge backlash, and it’s really scary. And obviously in the United States as well, there’s been, like, 100 anti-trans bills passed last year. It’s always important to me to be able to speak with levity about things. And that’s how I talk to my friends and how I understand my own gender—my own gender is like a kernel of corn glued onto some sticks.

There’s not a lot of room in that public conversation for ambiguity or uncertainty, but I think that’s a really common experience for people. That said, because everything’s so fraught, you’re expected to come down so hard with your opinion so clearly, and say “I am this.” And really, gender and sexuality are such dynamic and evolving and human things, it’s annoying to have to do that. So it was important for me to show that my character is still figuring it out as much as I am.

What does queerness mean to you personally?

I don’t really separate it from the rest of my life and who I am, so I don’t often think about my queerness, I just think about my day-to-day life and my relationships. I only have to think about it when I’m challenged on it, or put in a situation where I have to explain it or justify it.

Unfortunately that’s still going on, but having to do that all the time definitely can cumulatively lead to a sense of otherness, which I don’t appreciate. I feel very much like a citizen of the world and part of the world.

I remember when things first started being written about my comedy and I had never identified as anything before. I always dated men and women growing up, and then something was written about my comedy and it was like “gay Mae” or something like that. And then someone was like “aren’t you glad that you’re growing up in such a tolerant city, like Toronto is such a tolerant city.” And I was really freaking out, because I was like, “I thought I was part of this city and now suddenly I’m in the city that’s tolerating me.” But I never felt that way until someone said that, you know what I mean?

I worked in a comedy club here in Canada as a server and bartender for a few years and I so often saw marginalized comics getting tokenized or pigeonholed, so I definitely know what you mean.

I was really interested in the storyline with Scott (John Ross Bowie) and what it shows about shitty dudes in comedy. Because there’s a lot of high-profile shitty dudes in comedy like Louis C.K. or whatever, but there’s also a lot of low-profile local dudes in comedy who are just kind of part of that culture and take advantage of young people.

Can you talk a bit more about that and how your experience as a working comedian informed some of that storyline?

I’m not saying this defensively, because what you’re saying is really true, but there’s also a lot of really good guys in comedy. It was crucial for me to show that as well. All of my best friends are straight male comedians, so it was important to me not to demonize that community, because that community they raised me.

If you put a teenage girl or a teenage person in any industry, you’re gonna run into problems—especially if there’s alcohol and people with mental health stuff or addiction issues, which are rife in that industry. I started in 2001 when I was 13, and I’ve noticed just such a huge change in the atmosphere in comedy clubs, the behaviour. I think it’s getting so much better.

Credit: Netflix / Courtesy Everett Collection

Sometimes when we talk about it, we really put an emphasis on outing people and cancelling people. And that stuff is interesting and often important, but that’s not really the essence of what those experiences are about and what trauma is about. Often these things happen with someone you know or love or trust. It’s rarely a stranger and these things are really messy, and there are no winners. It doesn’t feel good to out someone. So that’s what I wanted to show, the messiness of it, and that there can be love there but you have to sort of put yourself first.

I think that’s a really good way of putting it. Clubs have been mostly closed, especially here in Canada, for the last year and a half. And I think a lot of people in the industry are seeing reopening as a time to “build back better,” to steal one of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s phrases. What are your hopes for the future of comedy, as we re-emerge into the world?

I think marginalized people can be tokenized or pigeonholed often, so I hope that stops being the case and that it’s a more sort of integrated and equal opportunity kind of atmosphere.

I’ve definitely felt a change. It used to be that if I were to talk about my relationships on stage, I would get feedback asking why did I have to talk about gay stuff all the time, but if a straight person talks about their relationship they didn’t think that.

So I think that’s all changing for the better. I would say I just can’t wait to get back on the road, and I’m really interested to see how audiences are feeling. Some of my friends are starting to gig again and some people are like, “Oh yeah, everyone’s euphoric to be out of their houses.” Other people say they’re really shellshocked and trying to learn how to be an audience again, and everyone looks a bit haunted.

Credit: Netflix / Courtesy Everett Collection

I think comedy, for all its flaws, is an incredibly unifying and human and life-affirming medium. It’s all about mining the shared human experience. That can only be good right now when everyone’s feeling so isolated.

The Zoom show doesn’t quite capture it?

Yeah, I’ve resisted doing a lot of them because they just feel so depressing.

I think season two ends with Mae and [their partner] George in as good of a place as you can say is a good place. Is there more to explore there?

I think we’ve got to leave it where it is and just do the two seasons. It’s what we’ve always said. We planned that because I think if you’re gonna keep going, you’d have to undo all the personal growth that these characters have made, and it would just feel really sadistic because you’d have to keep throwing problems at them. So, if we do ever see those characters again, I’d love for it to be something completely bizarre like a murder mystery or, you know, where Mae and George are a united front in some other genre.

What’s next for you? Is touring and getting back on stage the main direction you’re looking to?

I’m writing a movie with Joe [Hampson] who co-wrote Feel Good. And I’m developing another series with Netflix. And then, yeah, just trying to think about what the hell I’m gonna say on stage, and whether any of it will be relevant anymore. Just trying to write some standup. This is the longest I’ve gone without doing stand up since I was about 13.

I did a couple of shows last week—things are starting to open up here—and it felt great.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra