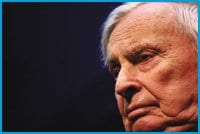

Gore Vidal is sounding a little tired. After 40-odd books and 81 years on the planet, the man who gave us such gay classics as The City And The Pillar and the invigoratingly vicious essay “Pink Triangle And Yellow Star” sounds very much in need of a pick-me-up.

Maybe it’s his age or the loss of his longtime partner Howard Auster in 2003 or his return to the US after 40 years as a transatlantic commuter with houses in Italy and California, but these days he seems rather tired of the contemporary scene.

Only two subjects really galvanize him: US politics and his own patriotism.

“Let’s get one thing straight,” he says within minutes of our meeting on the line from his home in the Hollywood Hills. “I was never an expatriate. I was never an Italian. I never was a European. I had no interest in any of that. I know writers are supposedly terribly poor and indigent and the begging bowl is always out, but I had two houses for 40 years, one in the Hollywood Hills and one in Campania in southern Italy. I lived back and forth.”

Yikes. He sold the house in Italy, he says, because he has an artificial knee and cannot walk, but returning to the US fulltime can’t have been that painful. He reportedly sold his Italian home on the Amalfi coast for $19.8 million. All I wanted to know was if moving back to his homeland had changed his perspective on American culture and politics. (“No,” is the short answer.) But then talking to Vidal is a little like cuddling with a porcupine; even the most innocuous overtures are greeted with a spike.

Vidal comes to Toronto Wed, Jun 6 for an onstage chat with New Yorker writer Adam Gopnik (Paris To The Moon). It’s part of the Luminato arts festival and Vidal says he’ll talk about anything his hosts desire, but my guess is the topics won’t include the Canadian Wheat Board.

In the past Vidal has been celebrated as much for his literary as his political criticism. More than one third of his selected essays (published as the massive United States: Essays 1952-1992) are devoted to matters literary. He has promoted such once neglected authors as Dawn Powell and Italo Calvino and written ravishing odes to Christopher Isherwood, VS Pritchett and especially his old friend Tennessee Williams (“Some Memories Of The Glorious Bird And An Earlier Self”).

But he doesn’t write about literature much anymore. He’s spent the past year reading Aristotle and has a lot to say, he says, but isn’t sure anyone is interested, or even that he wants to write about it. Not that public indifference has ever stopped him before. “Old books are no longer relevant in these swinging times,” he wrote almost 40 years ago in his memoir-cum-novel Two Sisters. But 11 years later he gave the world Creation, a crash course in religion and philosophy from the fifth century BC. “I go all the way from Socrates and Zoroaster to Confucius and to the Buddha,” says Vidal. It’s still the novel of his that he’d most like people to read.

He’s not terribly interested in contemporary literature, though, he says he doesn’t keep up. “Novelists don’t read each other very much. We have quite enough to do with our own work.”

Asked to name the greatest living writer, he mentions Italo Calvino, a writer who’s been dead for more than 20 years.

He’s aware of Edmund White but mostly, it seems, because White wrote a controversial play inspired by Vidal’s even more controversial articles on the Oklahoma City bomber Timothy McVeigh; Vidal thinks White has distorted both his ideas and his relationship with McVeigh (whom he never actually met). “I detest him [White],” says Vidal. “It’s as slimy a piece of work as you could ever find.”

The Booker Prize-winning Alan Hollinghurst fares slightly better. “I like him,” says Vidal. “I read something about a Swimming Pool Library, was that it? I thought that was good.”

Vidal has always had what you might call a complicated relationship with gay culture. Although he’s one of the fathers of the modern gay novel (and took a lot of heat for publishing The City And The Pillar in 1948), he’s never believed in the idea of sexual identity. There are homosexual acts, he says, but no homosexual people. He has said this so many times over the years that it’s hard to know when he first said it, but whatever the case, he has certainly never changed his mind.

“I don’t think it [sexual identity] exists…,” he says. “I think people who think there is such a thing are lunatics.”

Were he to define himself, he says, it would be as “a radical democrat, small D.” Sexuality has nothing to do with it.

“Sex is one of the last things on my mind at any point in my life…. I do [write about it] when it’s comic like Myra Breckinridge, of course I do. It’s a good subject because everybody takes it so seriously.” Suddenly his voice changes and he launches into a twitchy impersonation of what sounds like Lily Tomlin’s Ernestine the telephone operator. “‘Well, it’s really my identity that’s at stake here.’ And identity is so important.”

As for his views on politics, you could call him prescient. More than 40 years ago in one of his first published essays, Vidal wrote: “Most of the world today is governed by caesars. Men are more and more treated as things. Torture is ubiquitous.” That essay, “The Twelve Caesars,” was first published in 1959.

Today, he thinks that Americans have a “quasi-totalitarian government,” that Bush and Cheney should be impeached, and that Al Gore (a distant relation) is the Democrats best hope in 2008.

“[Gore] has a program and he is electable,” says Vidal. “He’s already been elected once, president, so he can do it again, particularly now that he is identified with saving the planet, something I think everybody agrees with.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra